Summary

A critical milestone in any peering relationship is the business review; and when it comes to business reviews, it’s all about preparation. Learn how Kentik can help.

Peering is more than just setting up sessions with any AS that will accept one. Peering can involve long-term relationships that require reviews and joint-planning to grow synergy. A critical milestone in any peering relationship is the business review – and when it comes to business reviews, it’s all about preparation.

So where to start? It can help to think about the review from two different perspectives: How does the relationship work from your side and, maybe even more importantly, how do you think it works from your partner’s point of view?

The first action is to read the partners’ peering policy.

The basics of peering policies

A peering policy is a declaration of a network’s intentions to peer. A network can state if it has the following:

- Open peering policy - Will peer with everyone and everywhere possible

- Selective peering policy - Will generally peer, but there are a set of requirements that define how mutual benefit can be gained from peering

- Restrictive peering policy - Will peer, but not seeking new peers and will generally decline any requests

It’s most common that networks agree to peer in all mutual locations when they agree to peer. That’s because, well, it’s mutually beneficial. Most networks will hand off the traffic as soon as possible. And peering in all mutual locations makes it more likely that the burden of carrying the traffic is evenly shared. When that’s not the case – for example, when an eyeball network peers with a content network – the parties work out an agreement on where to peer so it makes sense for both parties.

As for the networks with a selective peering policy, they usually document their requirements and lay out their justification for saying no to peering. The most common requirements or restrictions are:

- Ratio - The network requires a certain balance between the sent and received traffic from the potential peer

- Volume - The network requires a certain volume to justify the increased workload involved in setting up and maintaining connections

- Locations - The network requires a certain geographic overlap between the networks so they can hand off traffic most efficiently and save bandwidth within their own network

- Customers of an existing peer - If your network is a customer of an existing peer to your peering prospect, your traffic is already on a free connection for them and your traffic might be needed in a potential ratio-relationship between your peering prospect and your provider

With requirements from the peering policy in mind, it’s time to look at the traffic.

Analysis

Items to look out for:

- Routing - Is the traffic flowing as both parties want it to be?

- Quality - Is the traffic of even quality or do you see any connection or any destinations where the traffic is not performing as well as expected?

- Volume - Do you meet the requirements in the policy? What is the expected growth of traffic?

- Cost

1. Routing

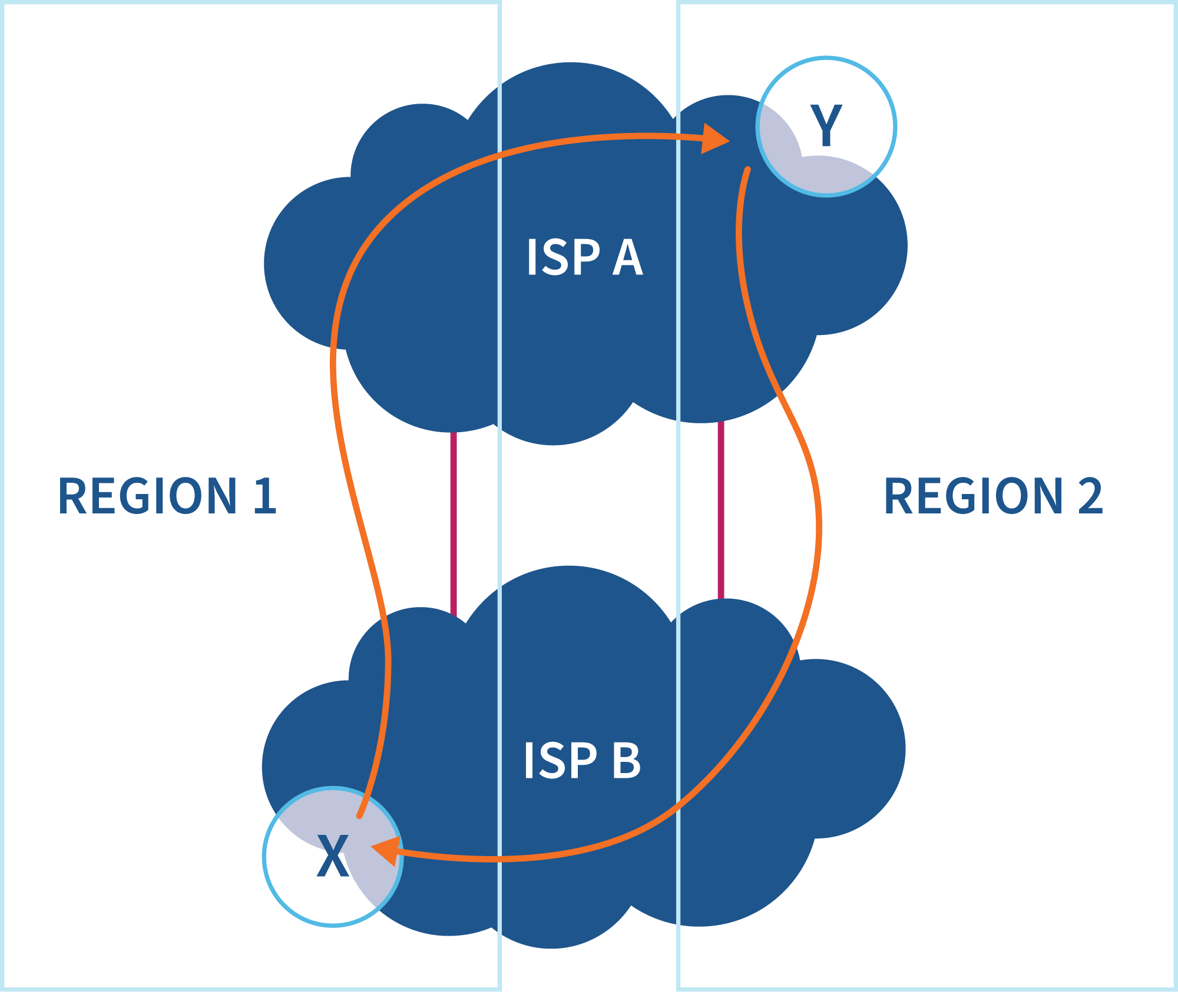

The peering policy gives a good indication of how the partner wishes the traffic to flow, but sometimes they have other requirements or interests. For example, a content distribution network (CDN) might not be interested in hot-potato routing (see below) at all. On the contrary, their business is to place the content as close as possible to the content consumers.

So, as a rule of thumb:

- Networks that transit traffic or networks that sell internet access favor hot-potato routing.

- CDNs prefer the shortest path possible from the interconnection to the consumers of the content.

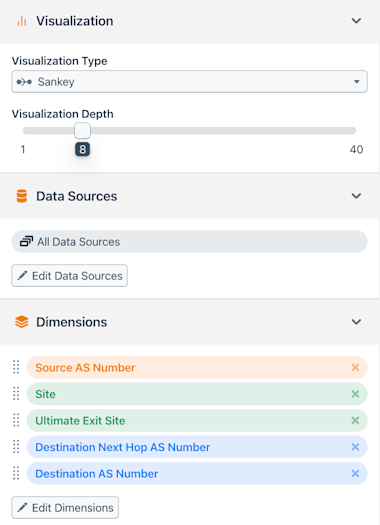

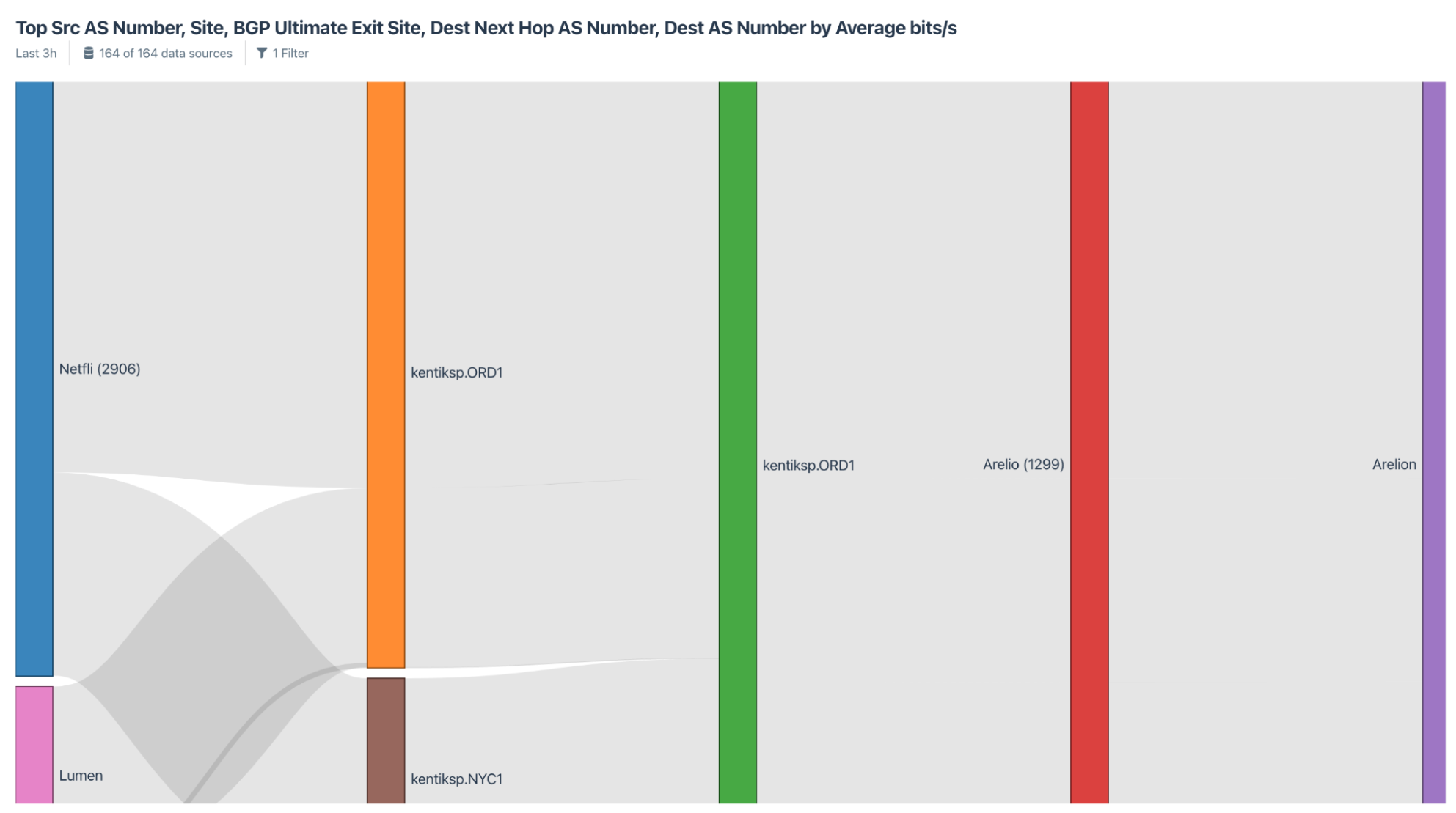

In this analysis we use the Kentik BGP Ultimate Exit to see how the traffic flows in and out of our network. We are checking both directions for the peer.

In our query we split the traffic by Source ASN, ingress site, Ultimate Exit site, destination, next hop ASN and destination ASN.

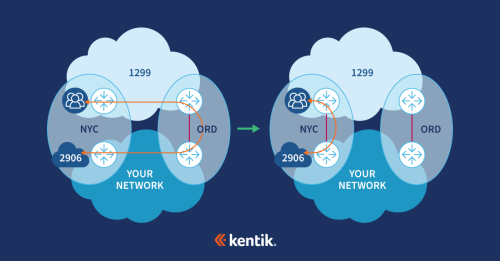

When looking at traffic from 1299 to destinations through our network, we see that most traffic enters in ORD1, but exits in ORD1 and in NYC1 and we can clearly see which next hop ASNs receive the traffic where.

Looking at the traffic going to 1299 via our network, we see some traffic from some of our customers ingress our network in NYC1 and flows to 1299 in ORD1.

Based on this analysis it would be great for us if 1299 would agree to adding a connection in NYC1, in addition to the one we have in ORD. We would hand off the traffic from our customer connection in NYC1 to 1299 in NYC1 and not carry it to ORD1.

But what does it look like on our partner’s side?

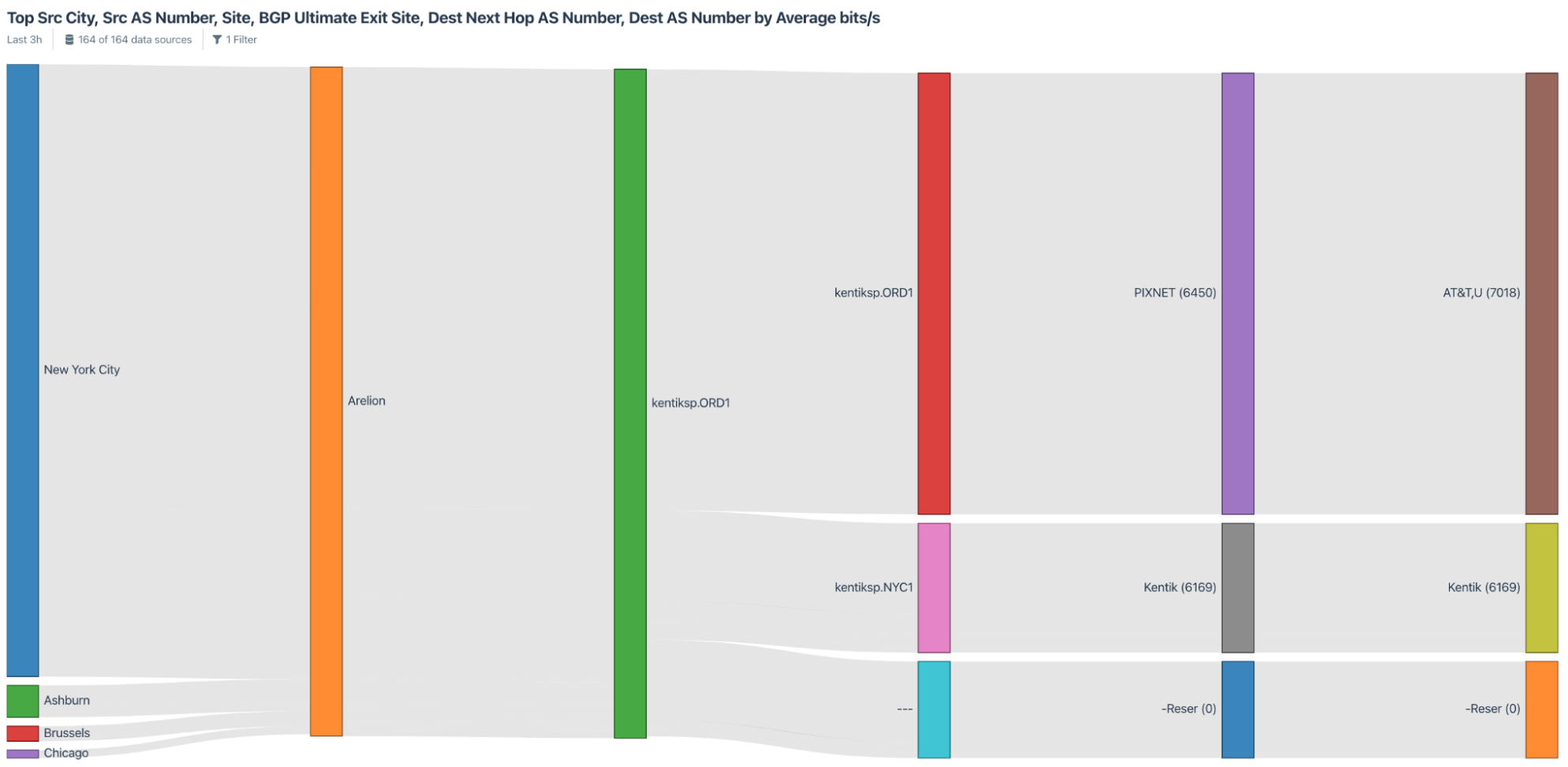

Adding geography for the source of the traffic to the dimensions, we learn that most of the traffic we ingress from 1299 is coming from New York City so it is likely the partner will agree to set up a connection there. The traffic will be handed off closer to the source and that way travels a shorter path.

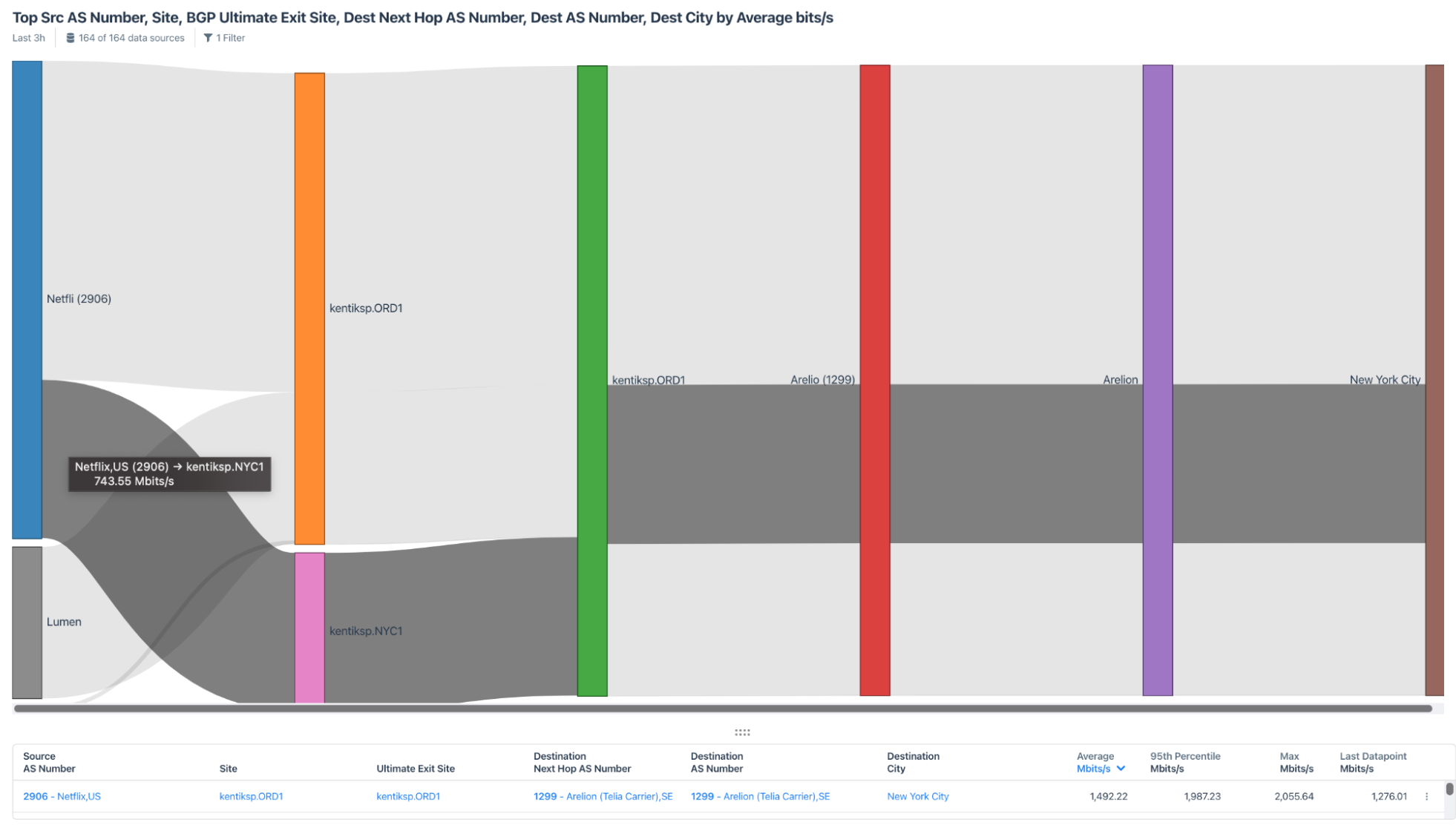

If we look at the traffic in the other direction - traffic from our customers to 1299, we see that we would fix a hairpin issue for our customer 2906.

We can translate the diagrams above to a network sketch of before and after.

2. Quality

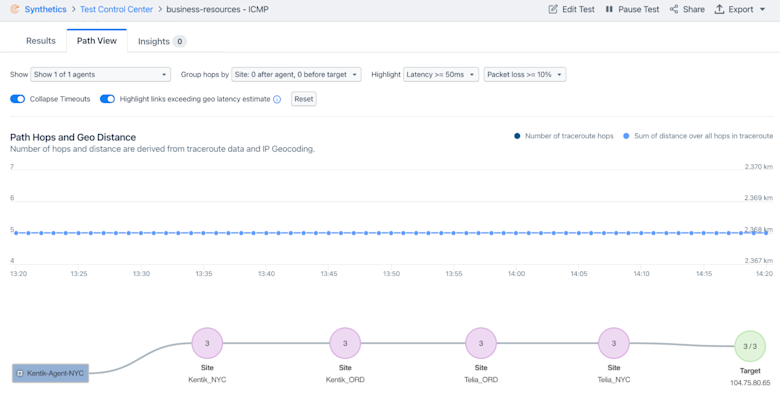

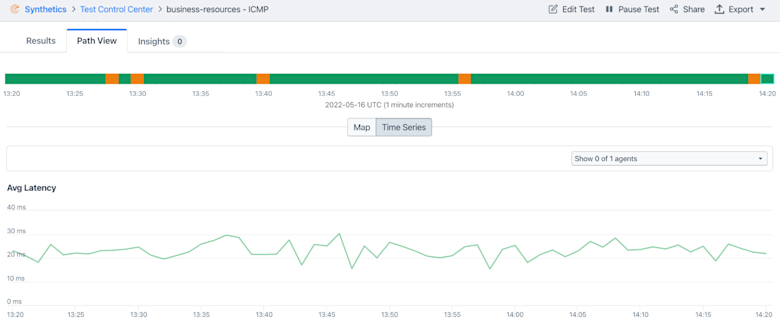

In general, synthetic tests enhance your flow-based connectivity monitoring and analysis. Synthetic tests are performed using Kentik’s platform of global agents in combination with private agents installed in your network. Synthetic tests help you see your network how others see it:

- Continuous path monitoring with alerts shows your connectivity works as planned and alerts you when it does not.

- Continuous monitoring of packet loss, latency and jitter with alerting means you are already on it before your customers experience any degradation.

- Automation could be triggered by alerts from the tests and do it for you.

- State of the internet measurements can help you quickly determine if an alert from a test from your network to an internet destination is due to internet weather or if you need to take action inside your network.

Monitoring the quality of the traffic for an individual peer is easy once you have found the good targets in the network. Combining your flow and synthetic platforms, like Kentik does, makes it easy to find the right targets to monitor.

3. Volume

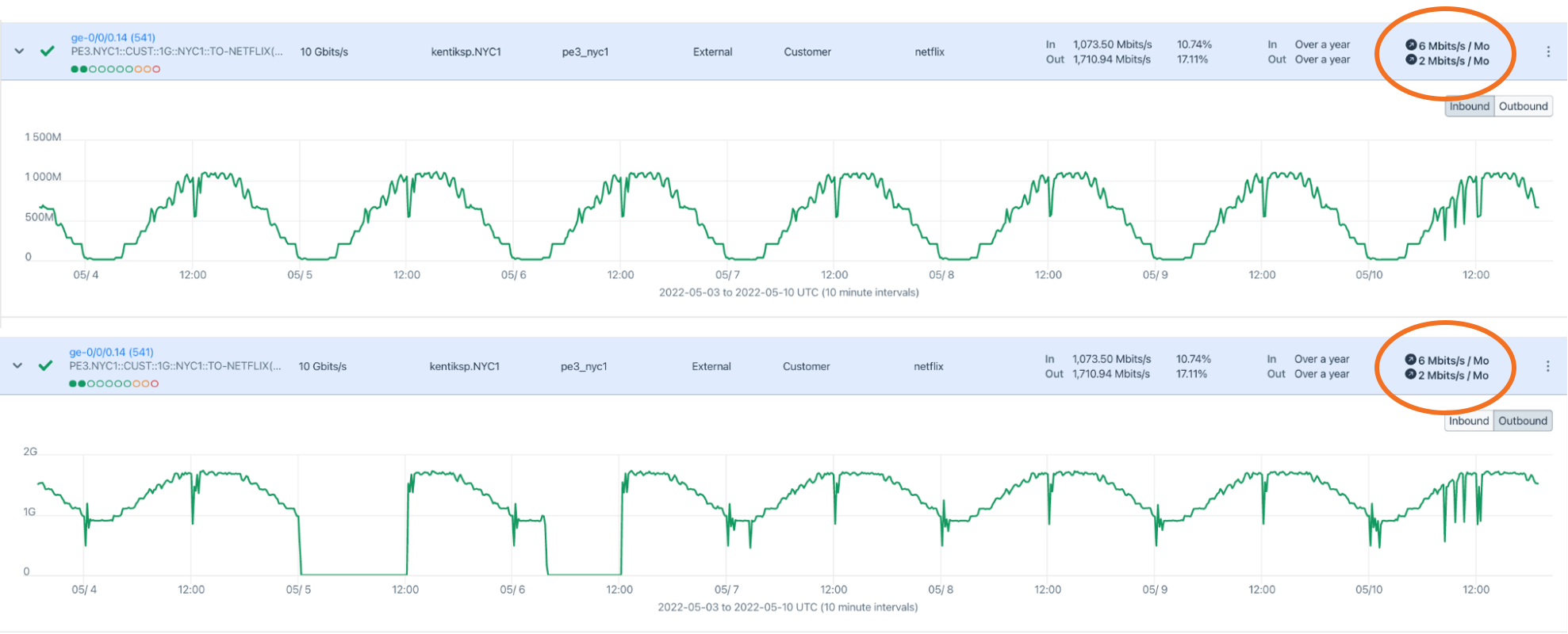

You will need to have a simple check of the ratio and the volume of traffic if your peering partner’s policy requires it. However, it’s more important to have a traffic forecast. What is the expected traffic growth? When you know this, you can discuss the capacity of the connections with the peering partner.

In the Capacity Planning workflow, this is an easy task.

We can see there is quite moderate growth and if that growth continues, there will still be enough capacity for more than a year ahead.

Since we know from the routing analysis that a good part of the traffic is due to our customer AS 2906, it’s a good idea to check their interface and see that their growth is consistent with the growth on the interface to the peer.

Now we know that we do not have capacity as a driver for the expansion of the connectivity to this peer, only the improvement for both parties by adding a connection in the metro where there is local traffic between our networks that is currently hauled to another metro and back.

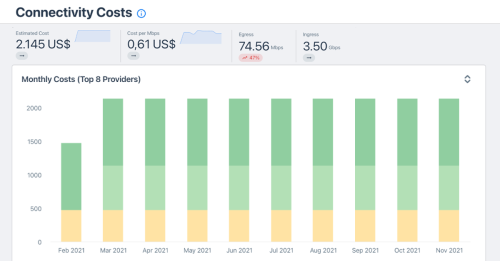

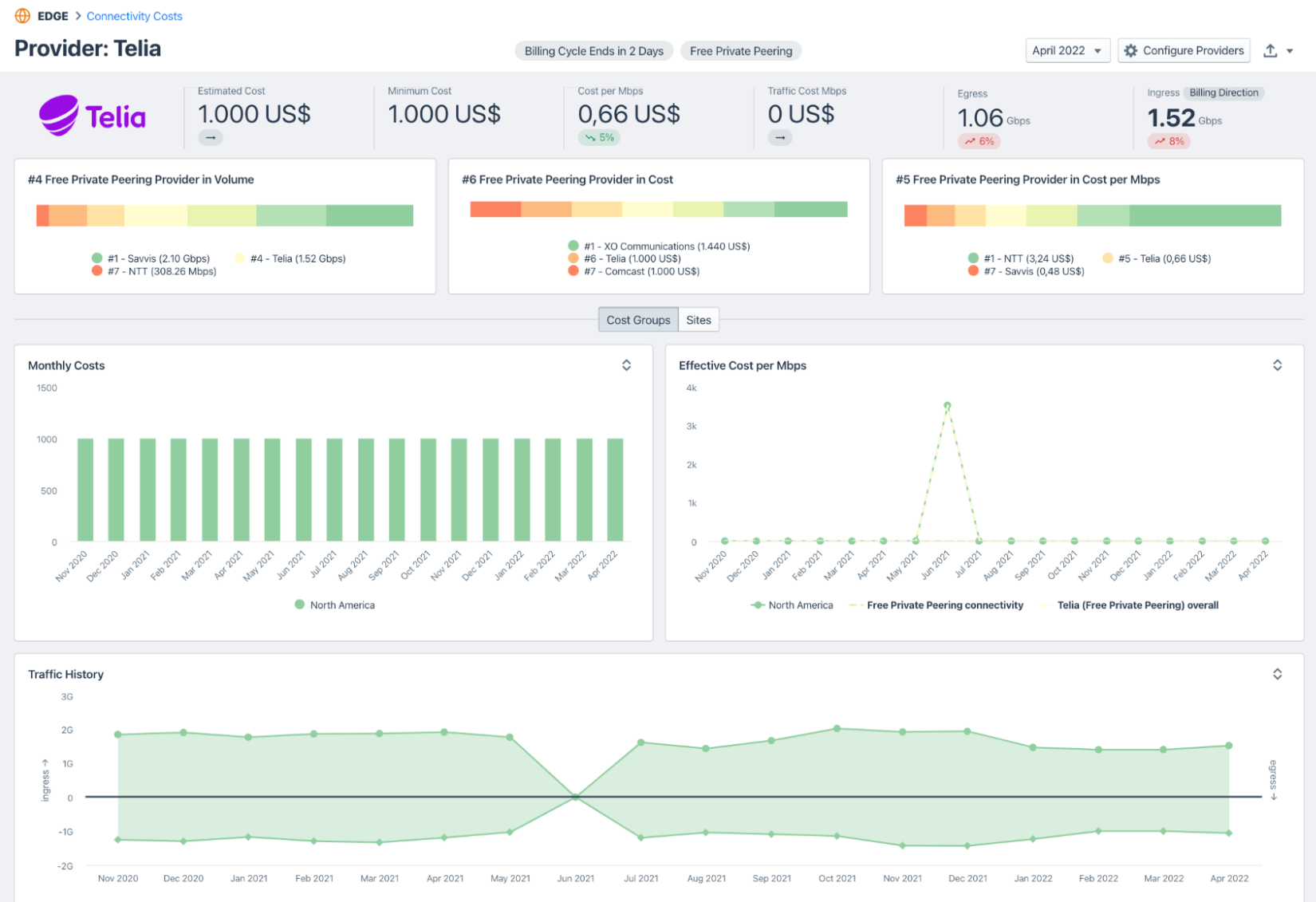

4. Cost

Knowing your cost for each of your peers is key to a good relationship. We discussed this in detail in the first of part of our blog series, “The peering coordinator’s tool box.”

Given that the traffic is not projected to grow much in this example, you can use this information to calculate what adding an extra connection will do to your cost for the peering with 1299 and decide if the improvement of the routing is worth it.

Interconnection choices and technology

We have not yet discussed how you are connected to the peer in this example.

Public peering is when you’re connected via an internet exchange. It is often the case that when traffic to a single peer over an internet exchange reaches a certain level, the connection is moved to a private connection. So, if the growth of this traffic alone will trigger the need to upgrade the port on the exchange, it can make more sense to move. However, sometimes this is only the case for one of the two parties in the relationship. You can often find guidelines in the peering policy for when traffic should be moved from public to private peering.

Private peering connections are connections where the traffic flows via either cross connects in a data center or sometimes via metro connections from one data center to another. It is common to share the cost of the cross connects. Often the requester pays for the first connection and then you take turns. But this is always part of the negotiations.

Try to predict whether the changes you would like to implement are reasonable from a cost perspective for your partner. Things to consider here are the evolution of interface speeds. Maybe your network is transforming from 100G to 400G, but your partner takes a bit longer so they will prefer adding more interfaces to the bundles – or vice versa. Try to have a solution ready for that discussion beforehand: Can we move to sites where the right equipment is in place? Can we split the cost of cross connects differently so the party that insists on bundles takes care of the cost alone?

In the case of our example, a potential solution to covering the extra cost of adding a connection in a new location, even though the traffic is not growing much, could be to set up sessions on an IXP in the metro area. Another approach might be to offer to pay the cost of the cross connects no matter whose turn it is to cover it.

Define your BATNA

The last thing to consider is your Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA). What will happen if your peering partner does not want to accommodate the needs that your analysis has uncovered? Is the as-is situation acceptable from your point of view or would it be better to find alternative paths for your traffic by moving it to transit?

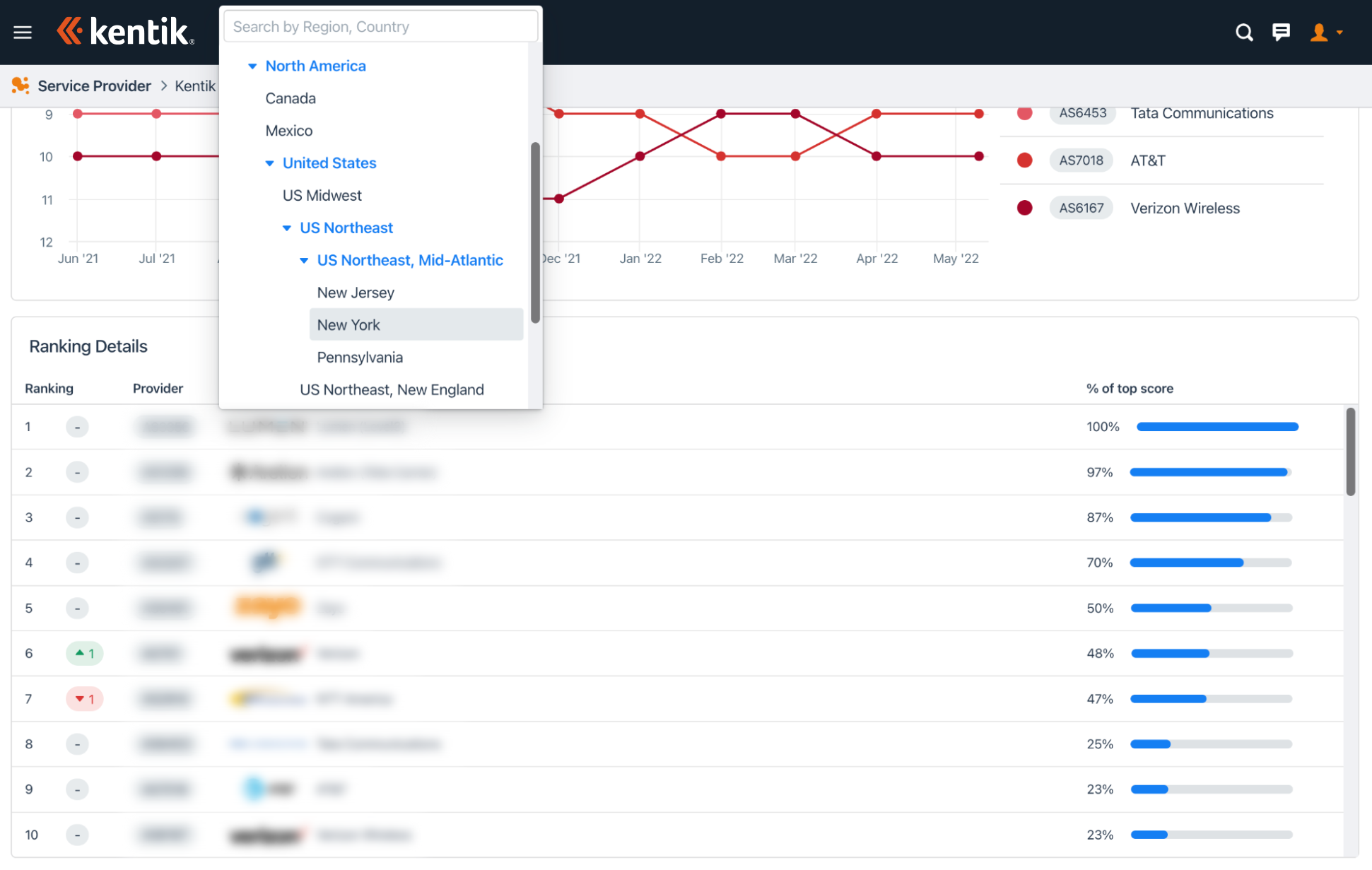

Kentik Market Intelligence (KMI) can help you find a good transit provider for the NYC metro area.

Picking the number one or two provider in the rankings will likely secure you good access to the consumers in the area for your customers, in this example in New York.

Conclusion

Now the game plan is set:

- We have identified a routing issue and documented a hairpin issue in the current setup.

- The solution is a new connection in the NYC metro.

- Since traffic is growing very slowly, there is not an immediate need for more capacity so, if fixing the hairpin is not important for the peer, we can:

- Offer to pay the cross connects, or

- Suggest a session on an IXP in the metro.

- If the status quo is unacceptable to us, our BATNA is to buy local transit and move the traffic to that connection.

Want to know more about this topic? Tune into my new webinar: How to prepare for a peering partner business review.