Summary

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is a policy-based routing protocol that has long been an established part of the Internet infrastructure. Understanding BGP helps explain Internet interconnectivity and is key to controlling your own destiny on the Internet. With this post we kick off an occasional series explaining who can benefit from using BGP, how it’s used, and the ins and outs of BGP configuration.

For an updated version of all four parts of this series in a single article, see “BGP Routing: A Tutorial” or download our Ultimate Guide to BGP Routing.

An effective BGP configuration is pivotal to controlling your organization’s destiny on the internet. Learn the basics and evolution of BGP.

BGP Basics: Routes, Peers, and Paths

Designed before the dawn of the commercial Internet, the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is a policy-based routing protocol that has long been an established part of the Internet infrastructure. In fact, I wrote a series of articles about BGP, Internet connectivity, and multi-homing back in 1996, and two decades later the core concepts remain basically the same. There have been a few changes at the edge (which we’ll cover in future posts), but these have been implemented as the designers anticipated, by adding “attributes” to the BGP specification and implementations. In general, BGP’s original design still holds true today, including both its strengths (describing and enforcing policy) and weaknesses (lack of authentication or verification of routing claims).

Why is an understanding of BGP helpful in understanding Internet connectivity and interconnectivity? Because effective BGP configuration is part of controlling your own destiny on the Internet. And that can benefit your organization in several key areas:

- Preserve and grow revenue.

- Protect the availability and uptime of your infrastructure and applications.

- Use the economics of the Internet to your advantage.

- Protect against the global security risks that can arise when Internet operators don’t agree on how to address security problems.

BGP and Internet connectivity is a big subject, so there’s a lot of ground to cover in this series. The following list will give you a sense of the range of the topics we’ll be looking at:

- The structure and state of the Internet;

- How BGP has evolved and what its future might hold;

- DDoS detection and prevention;

- Down the road, additional topics such as MPLS and global networking, internal routing protocols and applications, and other topics that customers, friends, and readers are interested in seeing covered.

For this first post we’ll get our feet wet with some basic concepts related to BGP: Autonomous Systems, routes, peering, and AS_PATH.

Routes and Autonomous Systems

To fully understand BGP we’ll first get familiar with a couple of underlying concepts, starting with what it actually means to be connected to the Internet. For a host to be connected there must be a path or “route” over which it is possible for you to send a packet that will ultimately wind up at that host, and for that host to have a path over which to send a packet back to you. That means that the provider of Internet connectivity to that host has to know of a route to you; they must have a way to see routes in the section of the IP space that you are using. For reasons of enforced obfuscation by RFC writers, routes are also called Network Layer Reachability Information (NLRI). As of December 2015, there are over 580,000 IPv4 routes and nearly 26,000 IPv6 routes.

Another foundational concept is the Autonomous System (AS), which is a way of referring to a network. That network could be yours, or belong to any other enterprise, service provider, or nerd with her own network. Each network on the Internet is referred to as an AS, and each AS has at least one Autonomous System Number (ASN). There are tens of thousands of ASNs in use on the Internet. Normally the following elements are associated with each AS:

- An entity (a point of contact, typically called a NOC, or Network Operations Center) that is responsible for the AS.

- An internal routing scheme so that every router in a given AS knows how to get to every other router and destination within the same AS. This would typically be accomplished with an interior gateway protocol (IGP) such as Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) or Intermediate System to Intermediate System (IS-IS).

- One or multiple border routers. A border router is a router that is configured to peer with a router in a different AS, meaning that it creates a TCP session on port 179 and maintains the connection by sending a keep-alive message every 60 seconds. This peering connection is used by border routers in one AS to “advertise” routes to border routers in a different AS (more on this below).

Introducing BGP

As explained above, the interconnections that are created to carry traffic from and between Autonomous Systems result in the creation of “routes” (paths from one host to another). Each route is made up of the ASN of every AS in the path to a given destination AS. BGP (more explicitly, BGPv4) is the routing protocol that is used by your border routers to “advertise” these routes to and from your AS to the other systems that need them in order to deliver traffic to your network:

- Peer networks, which are the ASs with which you’ve established a direct reciprocal connection;

- Upstream or transit networks, which are the providers that connect you to other networks.

Specifically, your border routers advertise routes to the portions of the IPv4 and IPv6 address space that you and your customers are responsible for and know how to get to, either on or through your network. Advertising routes that “cover” (include) your network is what enables other networks to “hear” a route to the hosts within your network. In other words every IP address that you can get to on the Internet is reachable because someone, somewhere, has advertised a route that covers it. If there is not a generally advertised route to cover an IP address, then at least some hosts on the Internet will not be able to reach it.

The advertising of routes helps a network operator do two very important things. One is to make semi-intelligent routing decisions concerning the best path for a particular route to take outbound from your network. Otherwise you would simply set a default route from your border routers into your providers, which might cause some of your traffic to take a sub-optimal external route to its destination. Second, and more importantly, you can announce your routes to those providers, for them to announce in turn to others (transit) or just use internally (in the case of peers).

In addition to their essential role in getting traffic to its destination, advertised routes are used for several other important purposes:

- To help track the origin and path of network traffic;

- To enable policy enforcement and traffic preferences;

- To avoid creating routing, and thus packet, loops.

Besides being used to advertise routes, BGP is also used to listen to the routes from other networks. The sum of all of the route advertisements from all of the networks on the Internet contributes to the “global routing table” that is the Internet’s packet directory system. If you have one or more transit provider, you will usually be able to hear that full list of routes.

One further complication: BGP actually comes in two flavors depending on what it’s used for:

- External BGP (eBGP) is the form used when routers that aren’t in the same AS advertise routes to one another. From here on out you can assume that, unless otherwise stated, we’re talking about eBGP.

- Internal BGP (iBGP) is used between routers within the same AS.

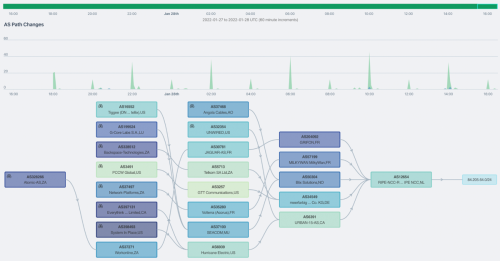

The AS_PATH attribute

BGP supports a number of attributes, the most important of which is AS_PATH. Every time a route is advertised by one BGP router to another over a peering session, the receiving router prepends the remote ASN to this attribute. For example, when Verizon hears a route from NTT America, Verizon “stamps” the incoming route with NTT’s ASN, thereby building the route in AS_PATH. (Note that when a route is advertised between routers in the same AS, using iBGP, the ASN for both routers is the same and thus AS_PATH is left unchanged.)

When multiple routes are available, remote routers will generally decide which is the best route by picking the route with the shortest AS_PATH, meaning the route that will traverse the fewest ASes to get traffic to a given destination AS. That may or may not be the fastest route, however, because there’s no information about the network represented by a given AS: nothing about that network’s bandwidth, the number of internal routers and hop-count, or how congested it is. From the standpoint of BGP, every AS is pretty much the same.

Additional uses for AS_PATH include:

- Loop detection: When a border router receives a BGP update (path advertisement) from its peers it scans the AS_PATH attribute for its own ASN; if found the router will ignore the update and will not advertise it further to its iBGP neighbors. This precaution prevents the creation of routing loops.

- Setting policy: BGP is designed to allow providers to express “policy” decisions such as preferring Verizon over NTTA to get to Comcast.

- Visibility: AS_PATH provides a way to understand where your traffic is going and how it gets there.

Conclusion… and a look ahead

So far we’ve just scratched the surface of BGP, but we’ve learned a few core concepts that will serve as a foundation for future exploration:

- Internet connectivity: the ability of a given host to send packets across the Internet to a different host and to receive packets back from that host.

- Autonomous system (AS): a network that is connected to other networks on the Internet and has unique AS number (ASN).

- Route: the path travelled by traffic between Autonomous Systems.

- Border router: a router that is at the edge of an AS and connects to at least one router from a different AS.

- Peering: a direct connection between the border routers of two different ASs in which each router advertises the routes of its AS.

- eBGP: the protocol used by border routers to advertise routes.

- AS_PATH: the BGP attribute used to specify routes.

In future posts we’ll get deeper into the uses and implications of the above concepts. We’ll also look at single-homed and multi-homed networks, how using BGP changes the connectivity between a network and the Internet, and who can benefit from using BGP. When we’ve got those topics down we can then look at the ins and outs of BGP configuration. Stay tuned…