Summary

This past year was another busy one for the internet. This year-end blog post highlights some of the top pieces of analysis that we published in the past 12 months. This analysis employs Kentik’s data, technology, and expertise to inform the industry and the public about issues involving the technical underpinnings of the global internet and how global events can impact connectivity.

This past year was another busy one for the internet. In this blog post, I will highlight some of the top pieces of analysis that we published in the past 12 months. This analysis employs Kentik’s data, technology, and expertise to inform the industry and the public about issues involving the technical underpinnings of the global internet and how global events can impact connectivity.

These posts are organized into two broad categories: major internet disruptions and BGP routing security.

Internet disruptions

Undersea volcano eruption near Tonga

Credit: Visible Earth/NASA

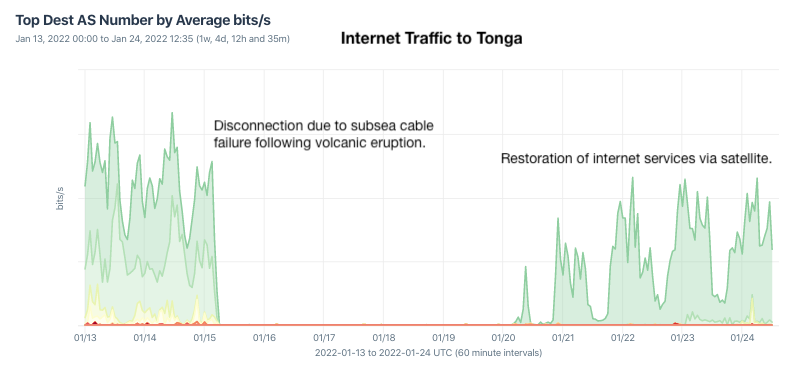

The year began with a bang – literally! The eruption of an undersea volcano on January 15 in the south Pacific devastated the island nation of Tonga, killing three of its people and knocking out voice and internet communications.

I wrote a blog post following the outage, giving some history of connectivity in Tonga, which I had previously covered. I spotted Tonga’s submarine cable first carrying traffic on August 5, 2013. The cable was funded by the World Bank and Asian Development Bank due to its status as a “thin route,” a term for a submarine cable that promises a small (or thin) return on investment. The undersea eruption destroyed this cable, disconnecting Tonga from the world.

On January 20, we saw the first internet traffic to Tonga as the island began restoring its connection to the world via connections from satellite operators Speedcast and Kacific.

Terrestrial outage in Egypt led to global impacts

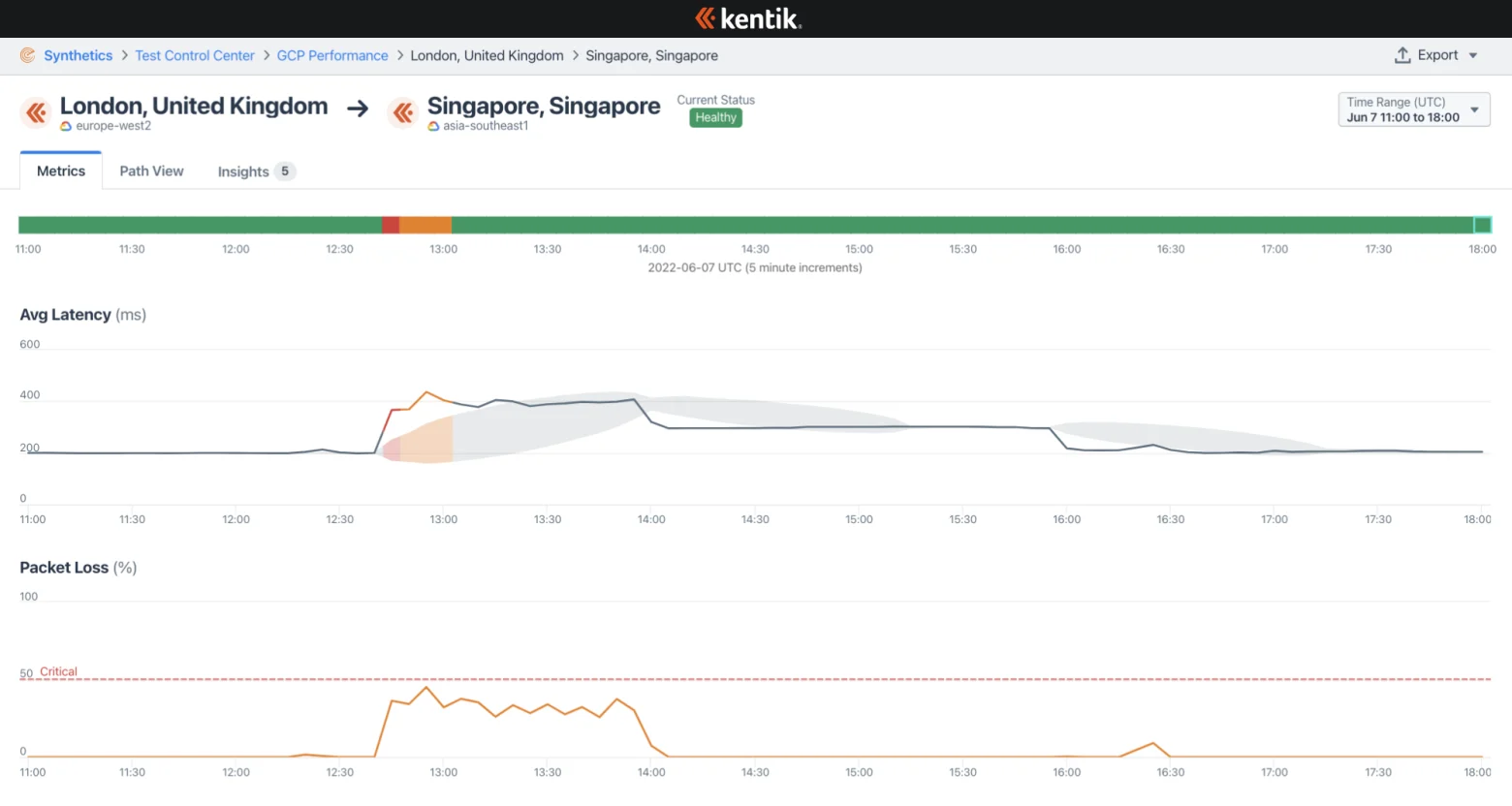

In June, a fiber outage in Egypt’s TransEgypt overland route, which connects submarine cables in the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea, caused international internet disruptions. In this blog post, we covered the outage by combining our data with that from Cloudflare Radar, IODA, and IIJ Research Lab. WIRED magazine later took this content about the history of Egypt’s role as a global internet chokepoint and expanded it into a feature story.

The post also offered a unique view from Kentik’s cloud measurements comparing how the outage impacted intra-cloud connectivity for Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud.

Conflict in Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues to be one of the biggest and most impactful stories of 2022. This brutal conflict has brought death and destruction to the Ukrainian and Russian people, as well as outages, DDoS attacks, and the rewiring of internet transit for the southern city of Kherson.

I covered all of these topics and more in an invited talk at NANOG 86 in Hollywood, California, in October. The talk was well-received and was listed at the top of the list of favorite talks by the program committee.

Additionally, I collaborated with the New York Times this summer to tell the story of the re-routing of internet service in Russian-occupied Kherson from Ukrainian transit to Russian transit. The Times’ story landed on the front page while we published an accompanying blog post that provided more technical detail and some comparisons to Crimea’s switchover to Russian transit in 2014.

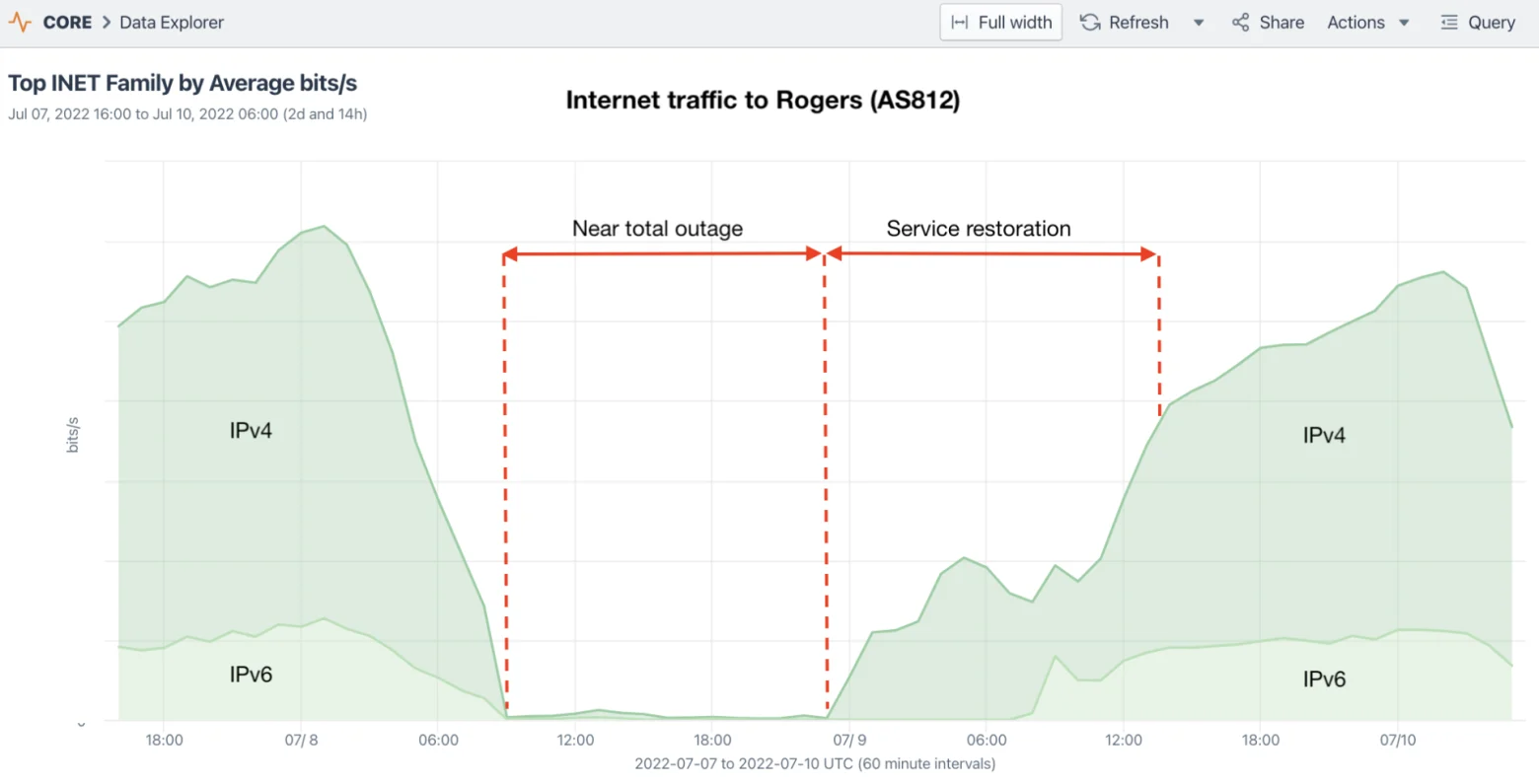

Rogers outage

In July, Canadian telecommunications giant Rogers Communications suffered what is arguably the most significant internet outage in Canadian history. In my blog post on the incident, we highlighted the impacts of the outage and tried to shed some light on the role of BGP, which had been the focus of blame in the initial accounts of the outage.

I’m here to say that BGP gets a bad rap during big outages. It’s an important protocol that governs the movement of traffic through the internet. It’s also one that every internet measurement analyst observes and analyzes. When there’s a big outage, we can often see the impacts in BGP data, but often these are the symptoms, not the cause. If you mistakenly tell your routers to withdraw your BGP routes, and they comply, that’s not BGP’s fault.

A couple of weeks later, the CRTC (Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission) published an explanation of the outage, which blamed an internal route leak. Basically, a filter had been removed, allowing the global routing table to be leaked into Rogers’ interior routing protocol, which overwhelmed their routers with a flood of internal routing updates.

The Rise of the Internet Curfew

Government-directed shutdowns in Cuba and Iran this fall led me to join up with Peter Micek of digital rights NGO Access Now to write a blog post that traced the history and logic motivating “internet curfews,” a tactic of communication suppression in which internet service is temporarily blocked on a recurring basis. We wrote:

The objective of internet curfews … is to reduce the cost of shutdowns on the authorities that order them. By reducing the costs of these shutdowns, they become a more palatable option for an embattled leader and, therefore, are likely to continue in the future.

The practice was first seen in Gabon in 2016 but reappeared in Myanmar last year following the military coup. Similar incidents in Cuba and Iran suggest this is, sadly, a tactic that we will see again in the future.

Protests in Iran

In September, a widespread protest movement had sprung up in cities across Iran following the death of Masha Amini while in police custody. In an effort to combat the protests, the Iranian government directed the three major mobile operators to begin disabling internet service across the country every evening before restoring service in the early hours of the following morning.

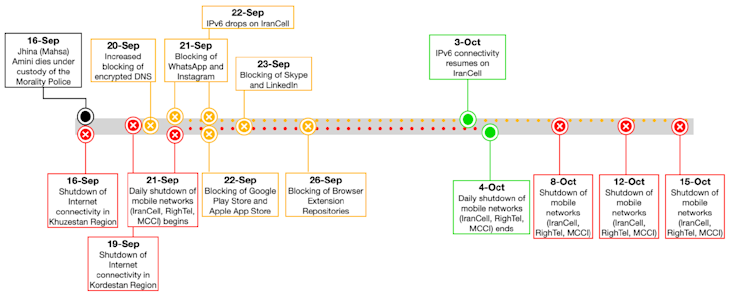

In addition to reporting on the internet disruptions in Iran, we contributed our data and expertise with that of multiple academic, industry, and civil organizations to produce a comprehensive report on the various internet disruptions in Iran in recent months. The timeline below summarizes the events covered in the report.

This joint effort echoed our collaboration with multiple other organizations last year to produce a comprehensive report on the internet disruptions following the military coup in Myanmar. It is work like this that resulted in Kentik being named as one of “the watchdogs guarding internet access” by the US State Department.

BGP routing security

Under the internet’s hood, there was also a lot of talk about BGP routing security this year. In June, I was invited to speak on BGP security at the NAMEX annual meeting in Rome, Italy. The title of the talk updated a local joke about the meaning of the Roman acronym SPQR: Sono Pazze Queste Rotte (they’re crazy, these routes 🤣). Watch the talk on YouTube.

RPKI ROV progress

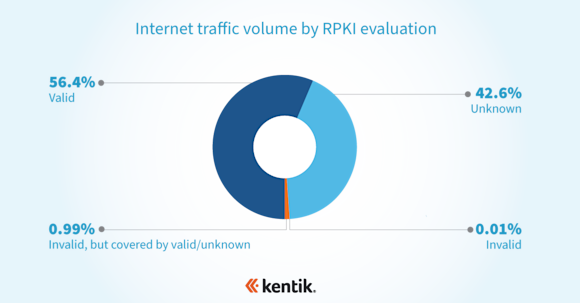

I teamed up with the preeminent routing security expert Job Snijders of Fastly on two analysis projects to shed some light on the progress made on the deployment of RPKI ROV. The first used Kentik’s aggregate NetFlow (annotated with RPKI ROV evaluations) to measure progress in RPKI ROA creation in terms of traffic volume instead of just counting prefixes or IP address space, as had been done in the past.

The conclusion was that, due to RPKI ROV deployments by major content providers and access networks, the majority of internet traffic (measured in bits per second) presently goes to routes with valid ROAs. This means that most internet traffic is eligible for the protection that RPKI ROV provides, further reinforcing the value of rejecting RPKI-invalid routes.

This analysis was presented at NANOG 84 in Austin, Texas, earlier this year:

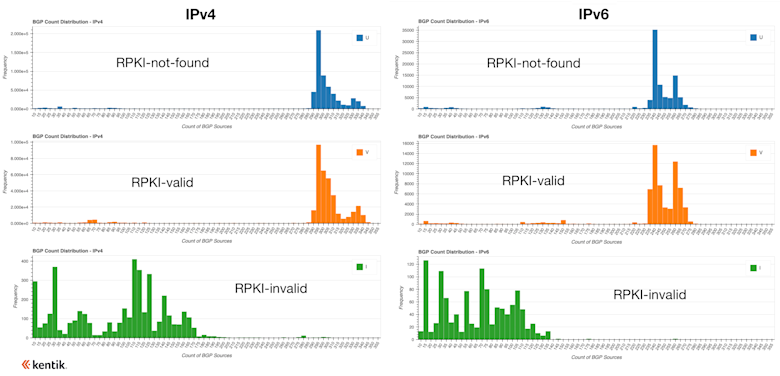

The second part of this analysis looked at the rejection of RPKI-invalid routes. As we wrote in our joint blog post detailing the conclusions:

ROAs alone are useless if only a few networks are rejecting invalid routes. The next step in understanding where we are at with RPKI ROV deployment is to better understand how widespread the rejection of invalid routes is.

So we ran the numbers and found that the evaluation of a BGP route as invalid reduces its propagation by anywhere between one-half to two-thirds! This is the system working as designed. As a result, we can be confident that the propagation of routes from a future origination leak, for example, will be suppressed in favor of the legitimate routes with valid ROAs.

From these histograms, we can see that invalid routes rarely, if ever, experience propagation greater than half that experienced by RPKI-valid and RPKI-not-found routes. In fact, many experience propagation significantly less than half, but the amount of reduction depends on a number of factors, including the upstreams involved in transiting the prefixes. Nonetheless, it is evident that RPKI ROV dramatically reduces the propagation of invalid routes.

Given that most internet traffic now flows towards routes with ROAs, we concluded that RPKI ROV is presently offering a significant degree of protection for the internet in the event of a routing mishap.

BGP hijacks targeting cryptocurrency

While the above analysis demonstrated that progress has been made in RPKI ROV, more sophisticated BGP hijack attacks remain a major unmitigated risk. This year saw two sophisticated attacks using BGP hijacking that were successful in the theft of large amounts of cryptocurrency.

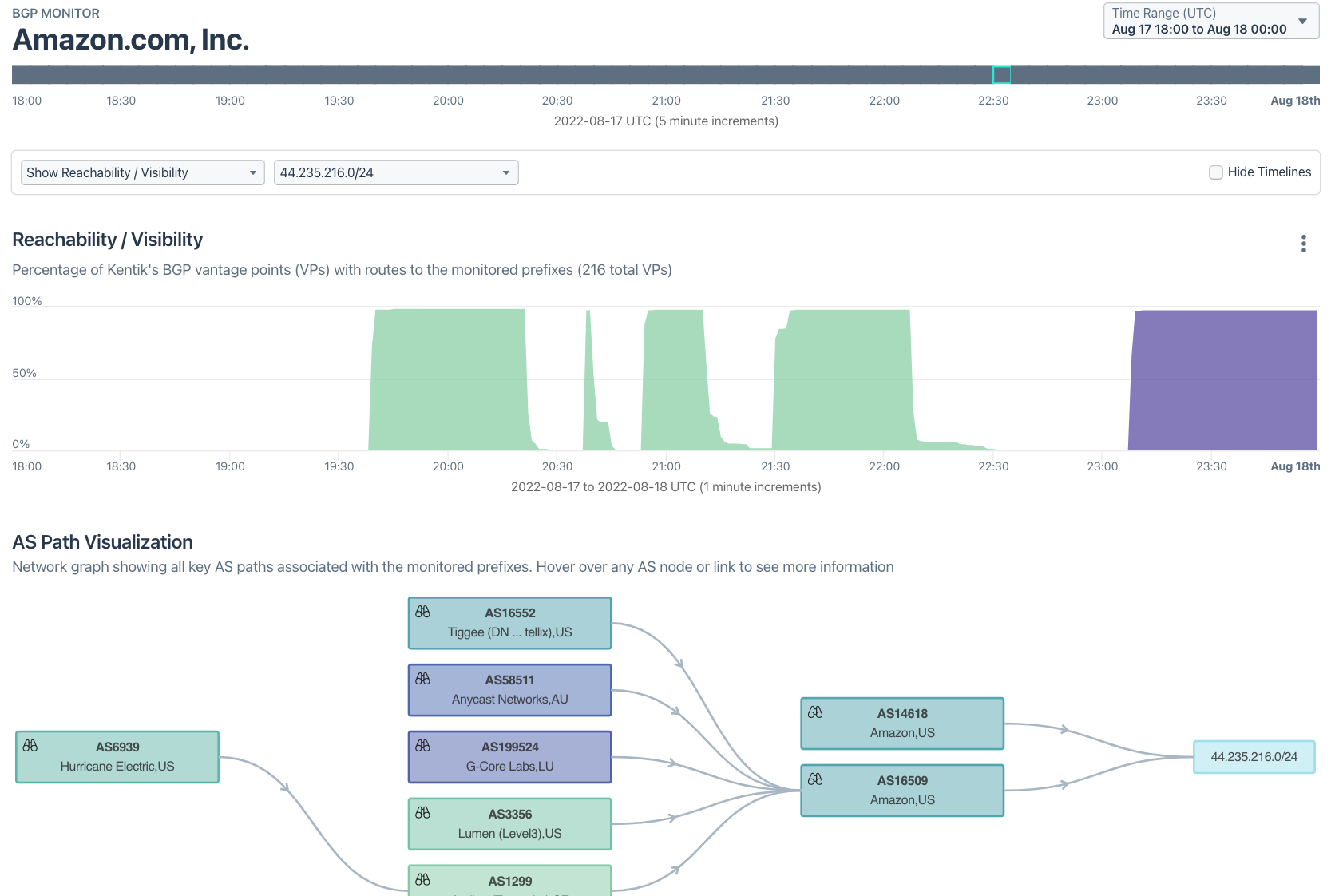

This led to a blog post reviewing the successful BGP hijack against AWS to attack the Celer Bridge, a service that allows users to convert between cryptocurrencies.

After the hijack in August, I tweeted out the following Kentik BGP visualization showing the propagation of this malicious route. The upper portion shows 44.235.216.0/24 appearing with an origin of AS14618 (in green) at 19:39 UTC and quickly becoming globally routed. It was withdrawn at 20:22 UTC but returned again at 20:38, 20:54, and 21:30 before being withdrawn for good at 22:07 UTC.

My conclusion was that although the attackers had effectively eluded RPKI ROV by forging an AS_PATH with Amazon’s ASN, there is reason to believe that tighter ROA definitions and better BGP route monitoring could have limited the efficacy of the attack and reduced the time it took Amazon to respond. Ars Technica was rather harsh on Amazon in their coverage of the incident based on our analysis.

Report collaborations

This year, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development published a series of technology-focused reports called the OECD Digital Economy Papers. Compiled by the OECD’s Directorate for Science, Technology, and Innovation (STI), these papers are intended to “better understand how information and communication technologies (ICTs) contribute to sustainable economic growth and social well-being.”

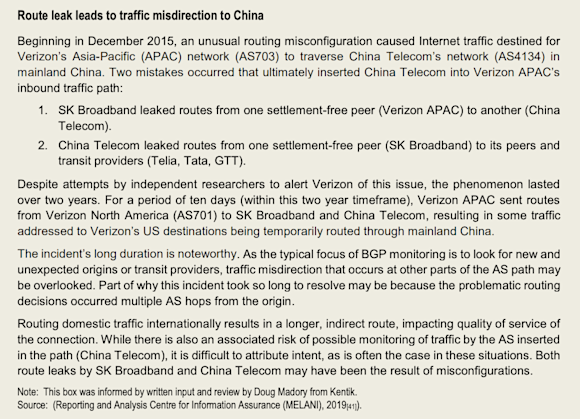

In October, the OECD published Routing security: BGP incidents, mitigation techniques, and policy actions, a report which included some of my prior analysis of BGP leaks and hijacks. One incident in particular that got highlighted was the misrouting of Verizon’s Asia-Pacific network (AS703) through China Telecom (AS4134) from 2015 to 2017.

This incident was also covered in the recent book The Digital Silk Road by Jonathan Hillman, a senior advisor to the US Secretary of State. Chapter 5 of that book is entitled A Crease In the Internet and covers my discovery and remediation of this traffic misdirection which lasted for nearly two years.

In a separate effort, I joined a team of subject matter experts to help the Broadband Internet Technical Advisory Group (BITAG) draft a comprehensive report on BGP routing security. BITAG is an organization that provides technical guidance to the US broadband industry on various topics, and periodically they form Technical Working Groups to draft technical papers intended to influence US policymakers on a technical subject.

In November, our Technical Working Group published Security of the Internet’s Routing Infrastructure, which explains issues surrounding BGP routing from the basics to recent BGP hijacks targeting cryptocurrency. It concludes with recommendations for both network operators and policymakers, such as the following:

- Respect the internet’s multi-stakeholder standards development process. If regulation is considered, set goals rather than specifying technologies.

- Engage the internet community to address regional policy incentive issues that slow the adoption of standardized routing security technologies.

- Fund the long-term monitoring programs needed to understand internet routing and the effects of changes over time.

Looking ahead to 2023

As we look ahead to the new year, there is no shortage of challenges and opportunities for internet connectivity around the world. We intend to continue producing timely, informative, and impactful analysis that helps inform the public and industry about internet connectivity issues.

Follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn to make sure you get notified as we publish posts in the future.