Suppressing Dissent: The Rise of the Internet Curfew

Summary

The populations in Cuba and Iran were only the latest to experience what has become an increasingly common tactic of digital authoritarianism: the internet curfew. This tactic, in which internet service is temporarily disabled on a recurring basis, lowers the costs and thus increases the likelihood of government-directed internet disruptions.

In the evening on September 30, people across Cuba found their internet service cut. The residents of this Caribbean nation had begun protesting their government’s tepid response to Hurricane Ian which had wrought destruction a week earlier. Internet service returned to normal the following morning, but this outage wasn’t caused by storm-related damage. This blackout was a deliberate act, a fact confirmed when service dropped out for the same period of time the following day.

Half a world away, Iranians were struggling with a similar version of episodic internet disruptions. A widespread protest movement had sprung up in cities across Iran following the death of Masha Amini while in police custody. In an effort to combat the protests, the Iranian government directed the three major mobile operators to begin disabling internet service across the country every evening before restoring service in the early hours of the following morning.

The people of Cuba and Iran were only the latest to experience what has become an increasingly common tactic of digital authoritarianism: the internet curfew. The word curfew has traditionally been used in the context of keeping people indoors during evening or nighttime hours. However, in the world of internet shutdowns, it has taken on a new meaning. In this blog post, we will discuss the origins and logic of this increasingly utilized tactic.

Evolution of a tactic

Egypt’s internet shutdown in the 2011 Arab Spring was a watershed moment for the internet community, but it was also extremely disruptive to the country’s economy. While the internet blackout was intended to disrupt the organization and coverage of the anti-government protests, it also disabled the government’s ability to communicate as well as crippled the operations of Egypt-based companies. An Egypt-style total internet shutdown involves significant collateral damage and can incur significant costs for the government, as well.

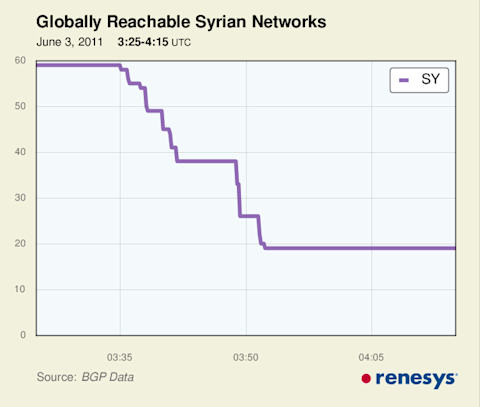

By the time Syria experienced their first internet shutdown five months later, the approach of taking down the internet appeared to have evolved. Instead of taking down all of the country’s internet communications, the embattled Syrian government only took down most of the country’s BGP routes. Routes belonging to mobile and residential networks were pulled, while those belonging to the government were left untouched.

The logic was presumably to focus on suppressing the communication of the Syrian citizens who were revolting while letting the Assad government and its allies continue to conduct business as usual. This was an early attempt at limiting the collateral damage of an internet shutdown.

First appearance in Gabon

Years later in September 2016, the West African nation of Gabon disabled its internet service for four days following a contested presidential election which led to deadly riots. When service returned, it came with a catch. Service was only up during the day, but was mostly taken down in the evening and at night.

These daily 12-hour national outages in Gabon were soon being referred to as an internet curfew. It marked the latest evolution in blocking access to the internet while minimizing blowback to the president, who continued to tweet his defense while everyone else in the country was either offline or blocked from reaching social media.

Afterward, the Hertie School’s Anita Gohdes, who researches political violence and state repression, concluded the following about the internet disruptions in Gabon:

The fact that the authorities in Gabon have limited the shutdowns to the evenings and nights speaks to their simultaneous fear of increasing unrest and their need to provide digital infrastructure to keep their citizens content. The fact that they are continuously doing it amidst unrest and uncertainty suggests the incumbent administration is going to continue its course of violent repression to maintain power.

Return in Myanmar

Then again, last year, in the aftermath of the coup in Myanmar, the military junta running the country issued multiple restrictions on the internet. Social media was blocked (leading to an inadvertent BGP hijack of Twitter), a weekend total shutdown, and later, another internet curfew: nightly internet blackouts of mobile internet service throughout the country.

Last year, we teamed up with the Open Observatory for Network Interference (OONI), Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), and Censored Planet to jointly publish an academic paper documenting the various disruptions in Myanmar using our combined datasets. The paper, A multi-perspective view of Internet censorship in Myanmar, was published in ACM SIGCOMM 2021 Workshop on Free and Open Communications on the Internet and relies on Kentik’s traffic data to document the internet curfew in Myanmar.

Latest internet curfews

In September 2022, widespread anti-government protests broke out in Iran after the death of a young woman in police custody. As a result, the Iranian government directed a series of actions to block the Iranian people’s access to multiple types of internet services.

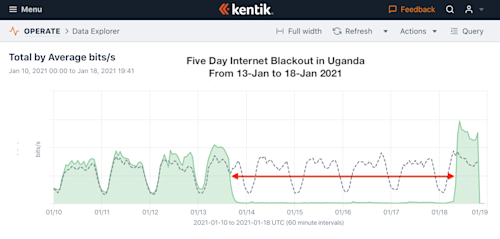

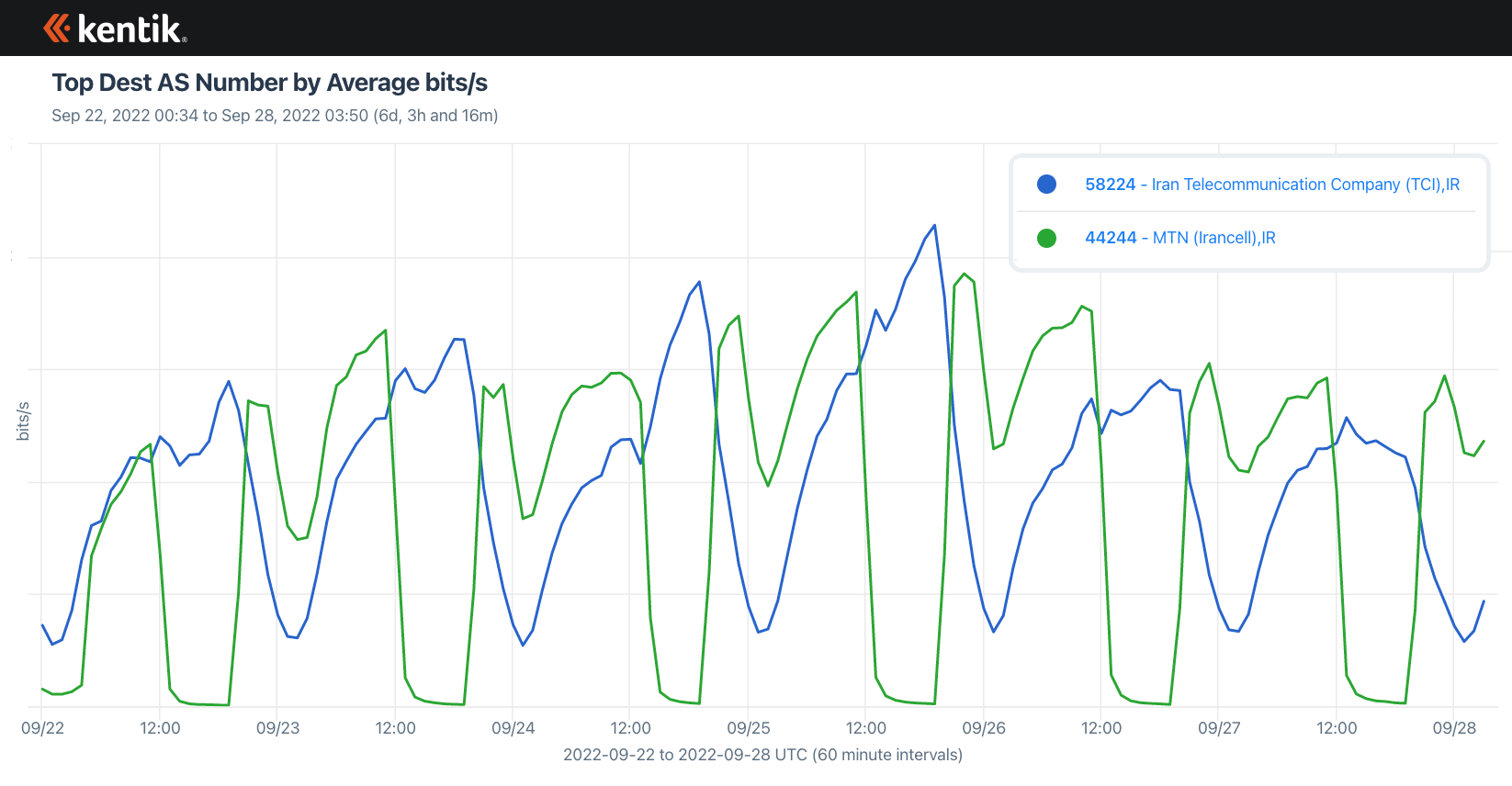

On September 21, the Iranian government directed the three major mobile operators of Iran (Irancell, Rightel, and MCCI) to block access to the internet from around 4pm to midnight local for almost two weeks. As was the case in the previous internet curfews, this tactic was intended to target the protestors in the streets while allowing the government and industry to continue to communicate.

In general, fixed-line services remained up during this period of time. In fact, we were able to observe a small uptick in traffic volume on fixed line service during the mobile shutdowns as some Iranians were able to find alternative sources of connectivity. However, this small increase in traffic was nowhere near enough to make up for the overall loss of traffic due to the nightly mobile shutdowns.

Additionally, while fixed line services might still have been connected, they also suffered from interference. Specific websites like Instagram and WhatsApp were blocked nationally and the region of Sistan-Baluchestan suffered a complete outage.

The graphic above shows the traffic volume in bits/sec seen to the largest mobile operator by traffic (Irancell, AS44244) and the largest fixed line operator by traffic (TCI, AS58224) during the first few days of the Iranian internet curfew. Note the slight increases in fixed line service (blue line) when the mobile service drops out (green line).

Making shutdowns more likely

When deciding on the method of suppressing communication, the authoritarian state must balance the disruptive aspects of internet shutdowns with its political goals of maintaining control over its population. If there is a possibility of being deposed from power, then any cost is acceptable for an authoritarian ruler.

However, not all civil unrest poses this level of risk to the authoritarian state. In the years following the complete disconnection in Egypt, there was hope that similar total disruptions might occur with less frequency due to the severe collateral damage they caused.

The thought continued that authoritarian governments may instead turn to a more surgical approach of just censoring social media and other unwanted internet services. However, increases in innovation and awareness of censorship circumvention technology over the past decade may have rendered this approach less effective, at least for those technically savvy internet users.

In the cat-and-mouse game of communication suppression, this innovation may have had the unintended consequence of making complete disruptions again seem necessary despite the costs: you can’t circumvent censorship if you are completely without internet service.

Over the past decade, Iran has been building a National Internet Network (NIN), ostensibly to allow the country to continue to function in the event that it was cut off from (or elected to cut itself off from) the outside world. Amir Rashidi, Director of Digital Rights and Security at the human rights organization Miaan Group has argued that Iran’s development of the NIN meant “cutting off access to the global internet is much less costly for the Iranian government—and thus more likely.”

The objective of internet curfews, like Iran’s NIN, is to reduce the cost of shutdowns on the authorities that order them. By reducing the costs of these shutdowns, they become a more palatable option for an embattled leader and, therefore, are likely to continue in the future. The task for civil society and organizations like Access Now is to maintain pressure on these governments by finding ways to increase costs for disrupting people’s access to the internet, and expose the hidden damage that these shutdowns inevitably cause to marginalized and vulnerable communities.