Summary

In this post, we dig into the impacts from the latest submarine cable cuts in the Red Sea from loss of transit for regional providers to the increase in latency for the major public clouds.

This past weekend saw the latest round of submarine cable cuts to impact internet connectivity between Europe and Asia. And once again they took place in the Red Sea, an historic problem area for subsea cables. In this post, I review some of the impacts that we observed in both the loss of transit in affected countries as well as increased latencies between public cloud regions using Kentik’s Cloud Latency Map.

Here we go again

Last year, we teamed up with WIRED magazine to publish a joint analysis into the timing and location of multiple undersea cable cuts in the Red Sea. The work lent additional support to the prevailing theory that a derelict ship, having been struck by Houthi missiles fired from Yemen, had dragged its anchor, cutting the cables.

In my post at the time, I described the Red Sea as a “dangerous place for submarine cables”:

Cargo vessels in the Red Sea awaiting their turn to traverse the nearby Suez Canal will drop anchor in the sea inlet’s relatively shallow depths. The possibility of an anchor snagging one or more submarine cables is very real and has occurred in the past.

In February 2012, three submarine cables were cut in the Red Sea due to a ship dragging its anchor. At the time, I wrote about the impacts on internet connectivity in East Africa, focusing on how much connectivity had survived what would have previously been a cause for a complete communications blackout in the region.

Well, here we are again. At the time of this writing, the cause and the exact location of the cable cuts has not been confirmed, although the prevailing theory is a ship anchor. Public reports have identified SMW-4 and IMEWE as impacted cables and private information points to additional breaks on the EIG and FALCON cables.

Let’s try to fill in a bit of this information vacuum.

Cloud impacts

Microsoft, to their credit, published a notice over the weekend alerting customers that “network traffic traversing through the Middle East may experience increased latency due to undersea fiber cuts in the Red Sea.” The timing Microsoft mentioned (“05:45 UTC on 06 September 2025”) doesn’t align with any impacts that I have observed, but there are multiple moving parts here.

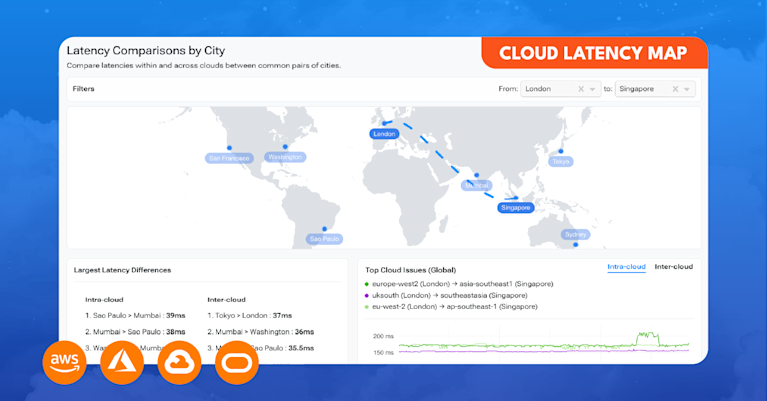

Due to the aforementioned information vacuum, initial media coverage of the cuts has focused on the impact to Microsoft’s cloud Azure, but other clouds were also impacted. In fact, Azure might have been one of the least impacted clouds based on measurements collected and published in Kentik’s Cloud Latency Map. Let’s run through some of the impacts that we observed.

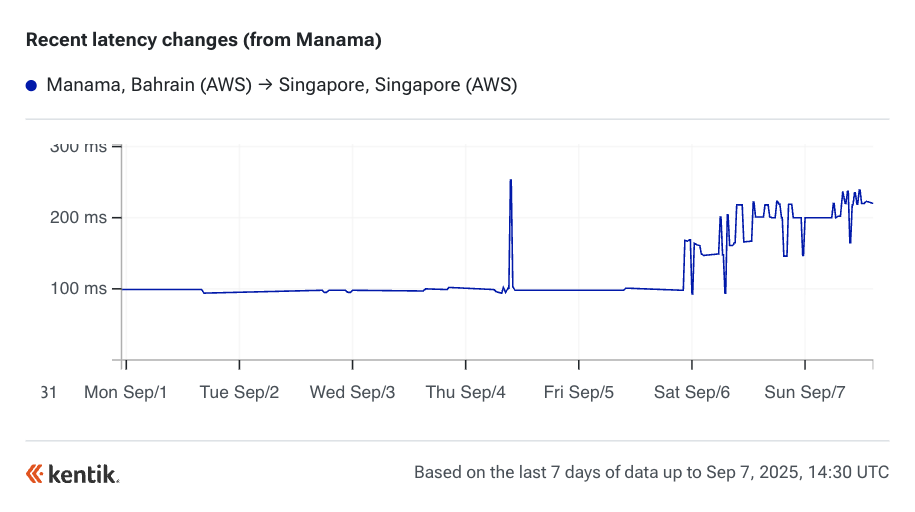

AWS’s cloud region in Manama, Bahrain me-south-1 experienced latency spikes to other cloud regions in the Gulf as well as AWS locations outside of the geographic region, including the example below to AWS in Singapore ap-southeast-1, which begins just after 22:30 UTC on September 5:

As a general rule, inter-cloud traffic, exchanged between different public clouds, experiences performance impacts greater than intra-cloud traffic, where a single cloud’s networking team controls both ends of the connection and can better re-engineer traffic to utilize backup routes, minimizing any impact.

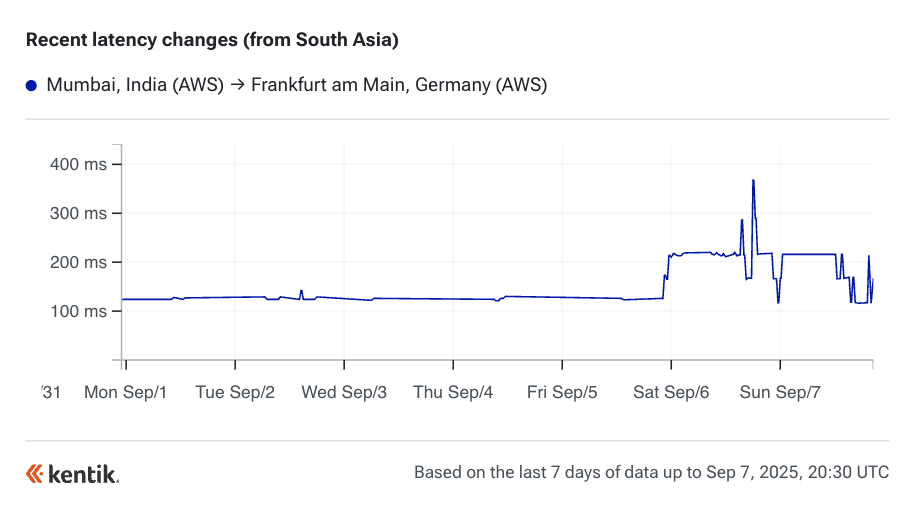

However, in this case, we’re seeing many examples of intra-cloud measurements experiencing latency spikes on the order of days, such as the measurement below between AWS’s ap-south-1 in Mumbai, India, and eu-central-1 in Frankfurt, Germany.

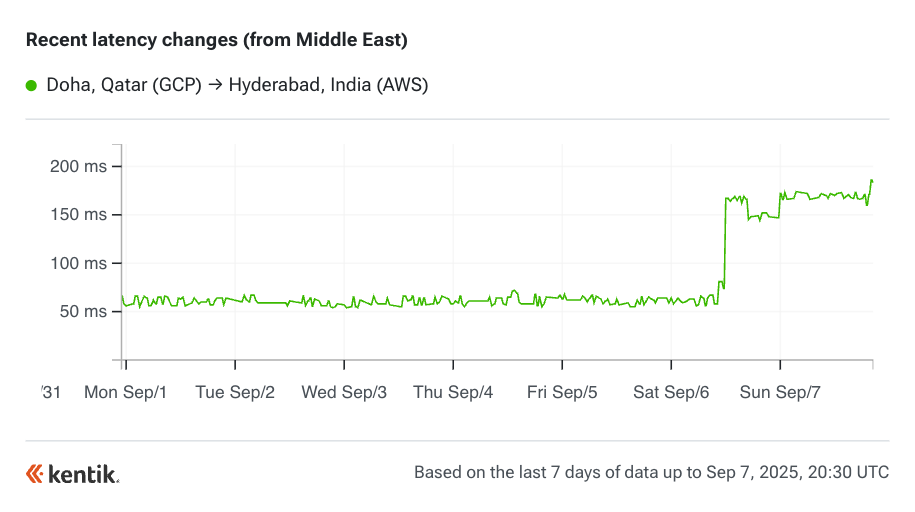

Measurements to and from GCP’s me-central1 region in Doha, Qatar, experienced a jump in latency to other cloud regions in the Gulf as well as to those in Europe and South Asia, such as the example below to AWS ap-south-2 in Hyderabad, India which experienced a latency increase around 11:00 UTC on September 6, hours after the impacts seen elsewhere in this section.

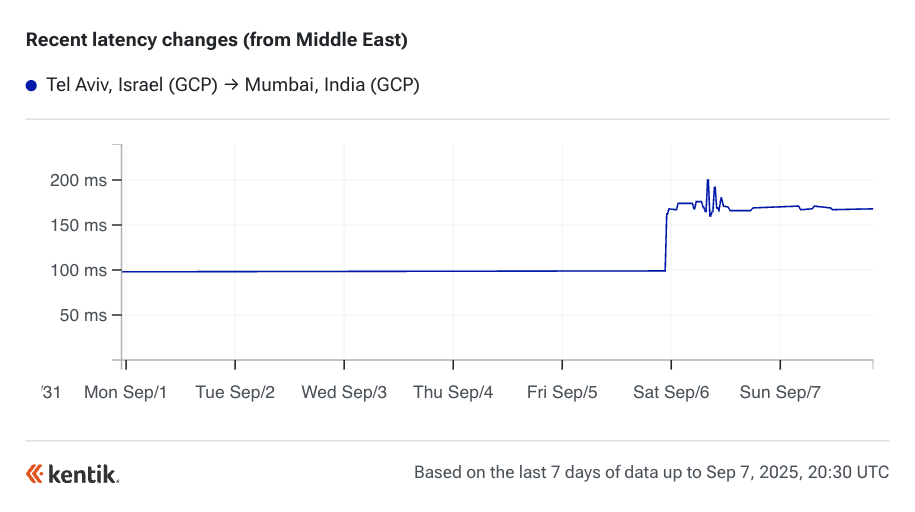

GCP’s me-west1 in Tel Aviv, Israel, experienced a jump in latency to asia-south1, their cloud region in Mumbai, India, as illustrated below.

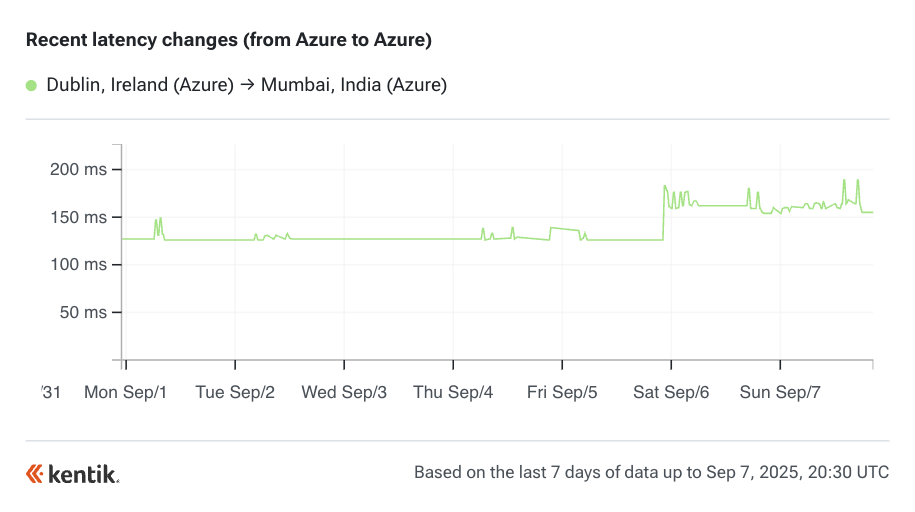

And, of course, as advertised, Azure experienced increased latency for some routes that pass through the Red Sea, such as the connection between northeurope (Dublin, Ireland) and westindia (Mumbai, India), illustrated below.

The observed impact between switzerlandnorth (Zurich, Switzerland) and centralindia (Pune, India) is another example of increased latency between two Azure cloud regions.

The lesson here is that, despite their size and strength, the hyperscalers must rely on the same submarine cable infrastructure that the rest of us little people do.

Transit impacts

Yemen was the focus of last year’s Red Sea cable cuts, so let’s begin there. As you may recall, the country (as well as its internet) is divided in two, with the Houthi-controlled government holding Sanaa and thus YemenNet (AS12486, AS30873), while the former government holds Aden and has established Aden Net (AS204317) as their source of connectivity.

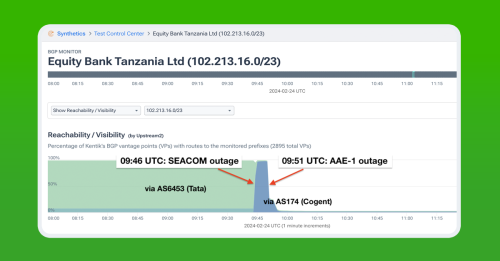

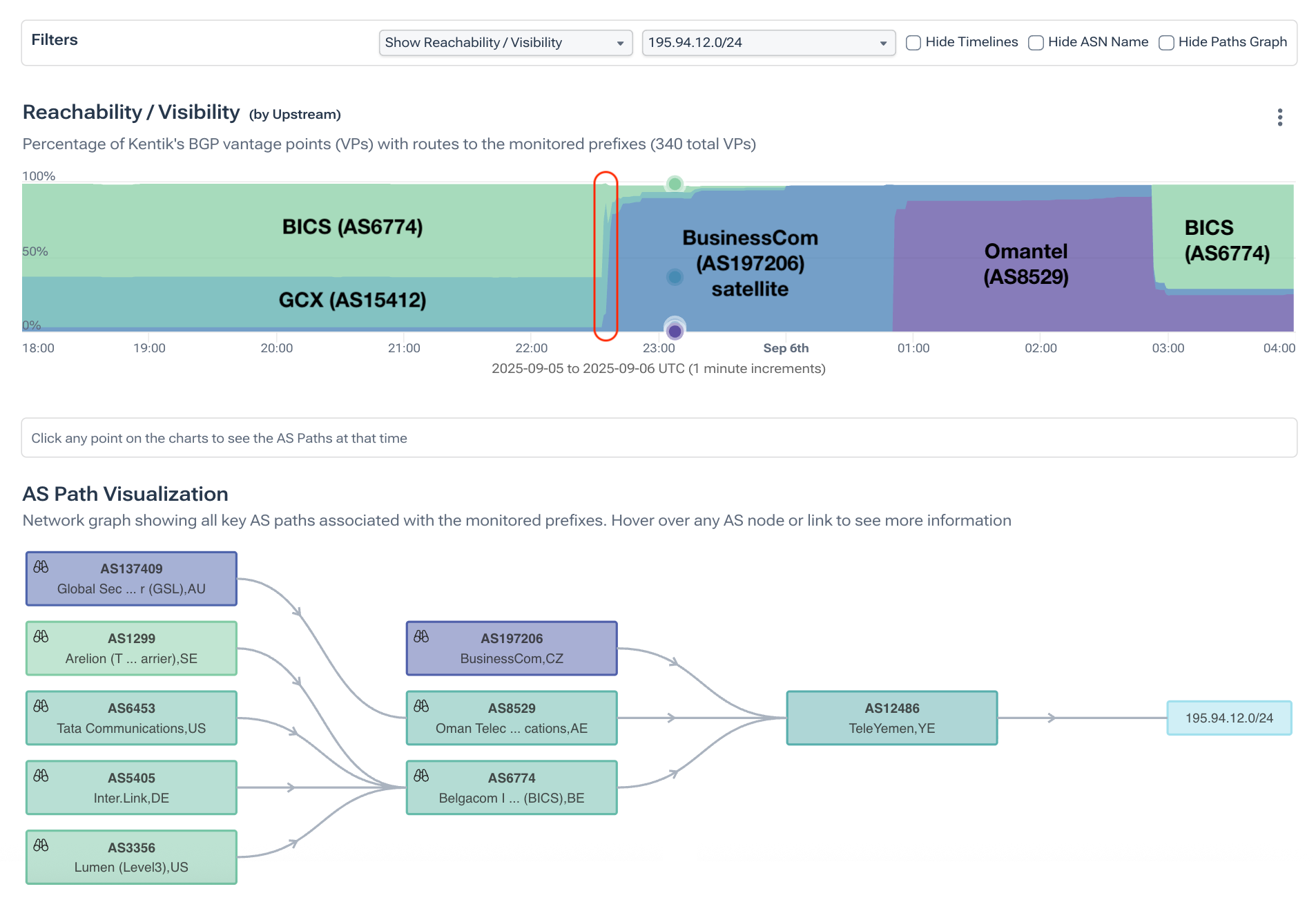

At the primary moment of disruption, we saw YemenNet (aka TeleYemen) lose transit from BICS (AS6774) and Global Cloud Xchange (AS15412) at 22:32 UTC and revert to satellite service from BusinessCom (AS197206) in the case of the network illustrated below:

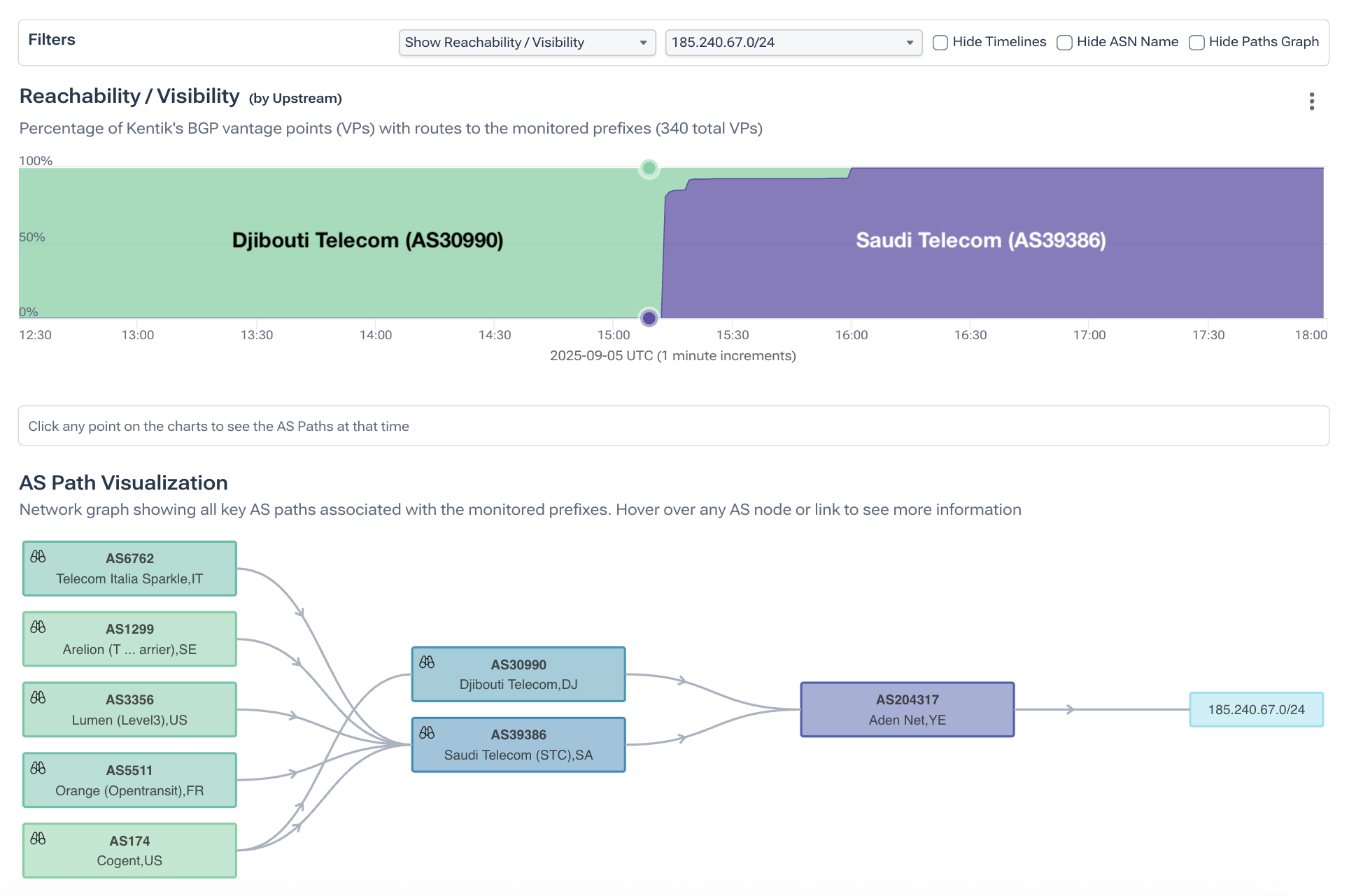

Aden Net also experienced an impact from the cable cuts, losing their transit from Sudatel across the Red Sea. At 15:13 UTC on September 5, AS204317 lost transit from Djibouti Telecom (AS30990), reverting to Saudi Telecom, their primary transit provider.

This change occurs hours earlier than most of the other impacts, but with four separate cable failures, it’s hard to rule out what might not be a minor impact of the loss of one of those cables.

United Arab Emirates

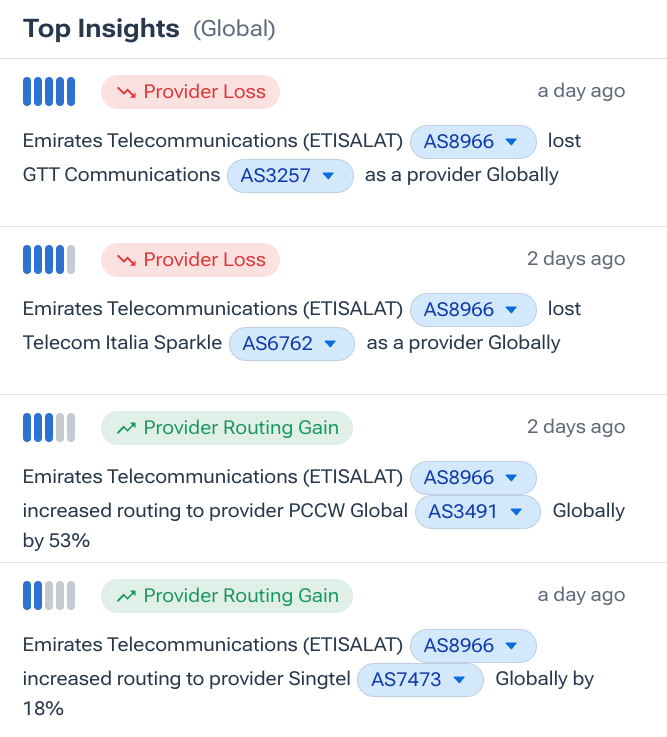

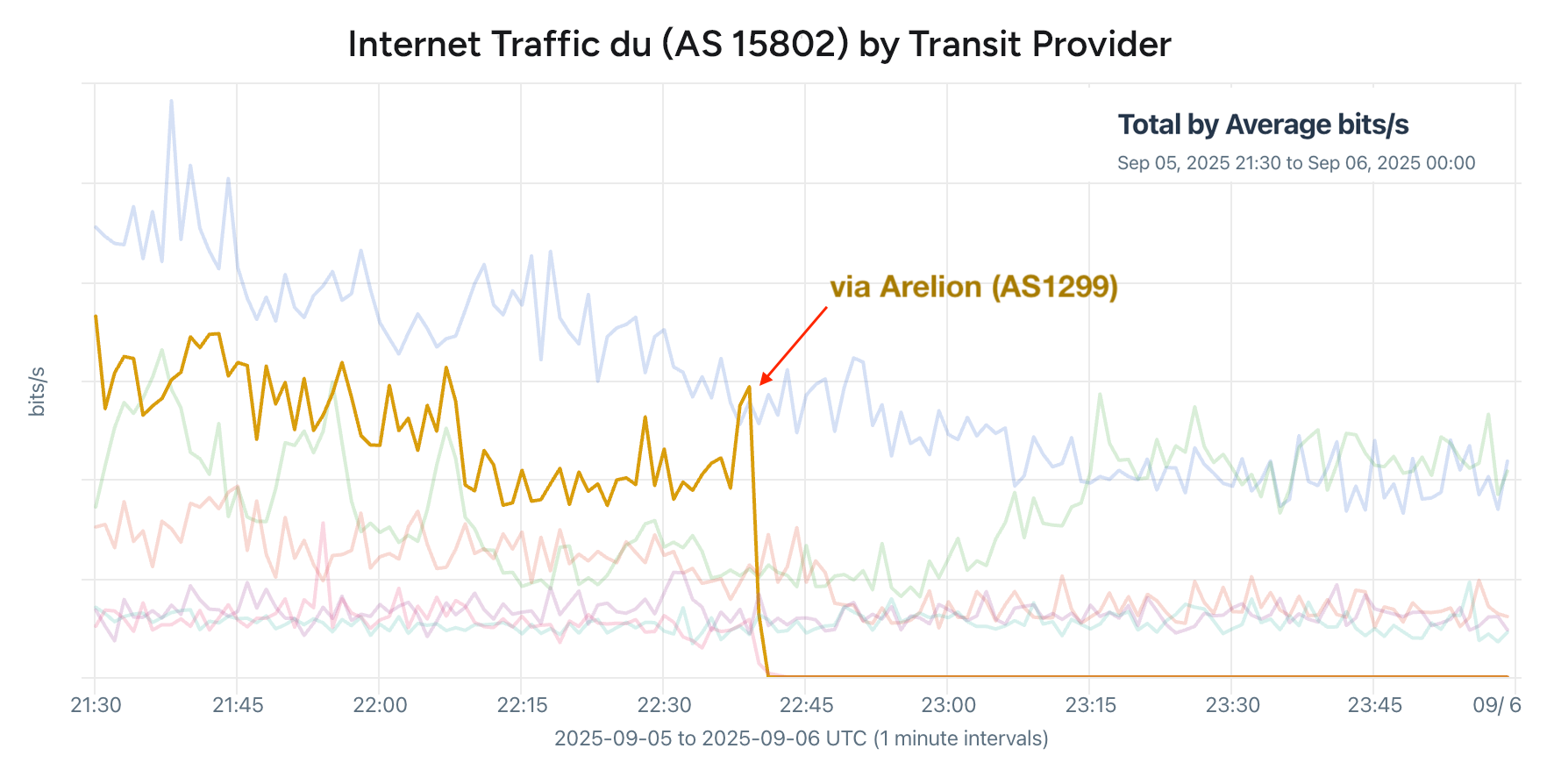

The United Arab Emirates market is dominated by Etisalat and du, each of which lost transit carriers due to the cable breaks. Etisalat (AS8966) lost transit from Telecom Italia (AS6762) and later GTT (AS3257), while du (AS15802) lost transit from Arelion (AS1299) and Tata (AS6453), all occurred just after 22:30 UTC on September 5.

Below is a screenshot from Kentik Market Intelligence reporting the loss of two of Etisalat’s transit providers followed by increased routing from two of their remaining providers.

We can also see the impact from a traffic standpoint. The screenshot below highlights traffic from Arelion (AS1299) to du (AS15802) around the time of the cut. It goes to zero, along with traffic from Tata (AS6453), at 22:40 UTC on September 5 as a result of the cable cuts.

India

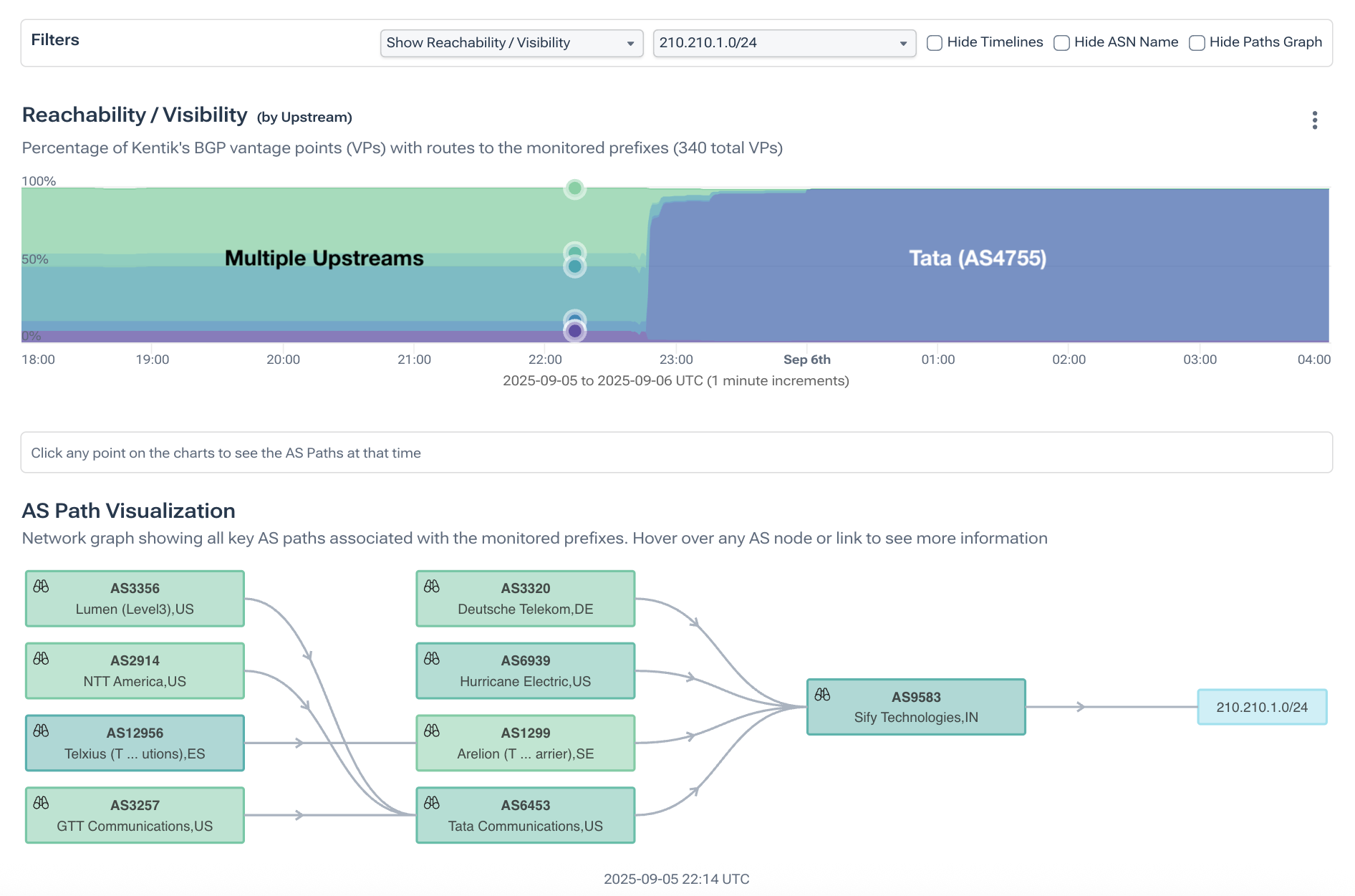

Sify (AS9583) lost multiple transit providers, including Cogent (AS174) and Tata (AS6453) at 22:47 UTC on September 5. The visible impacts to AS9583 were varied, but the screenshot below shows one network (210.210.1.0/24) being shifted over to Tata (AS4755) at the time of the cable cut.

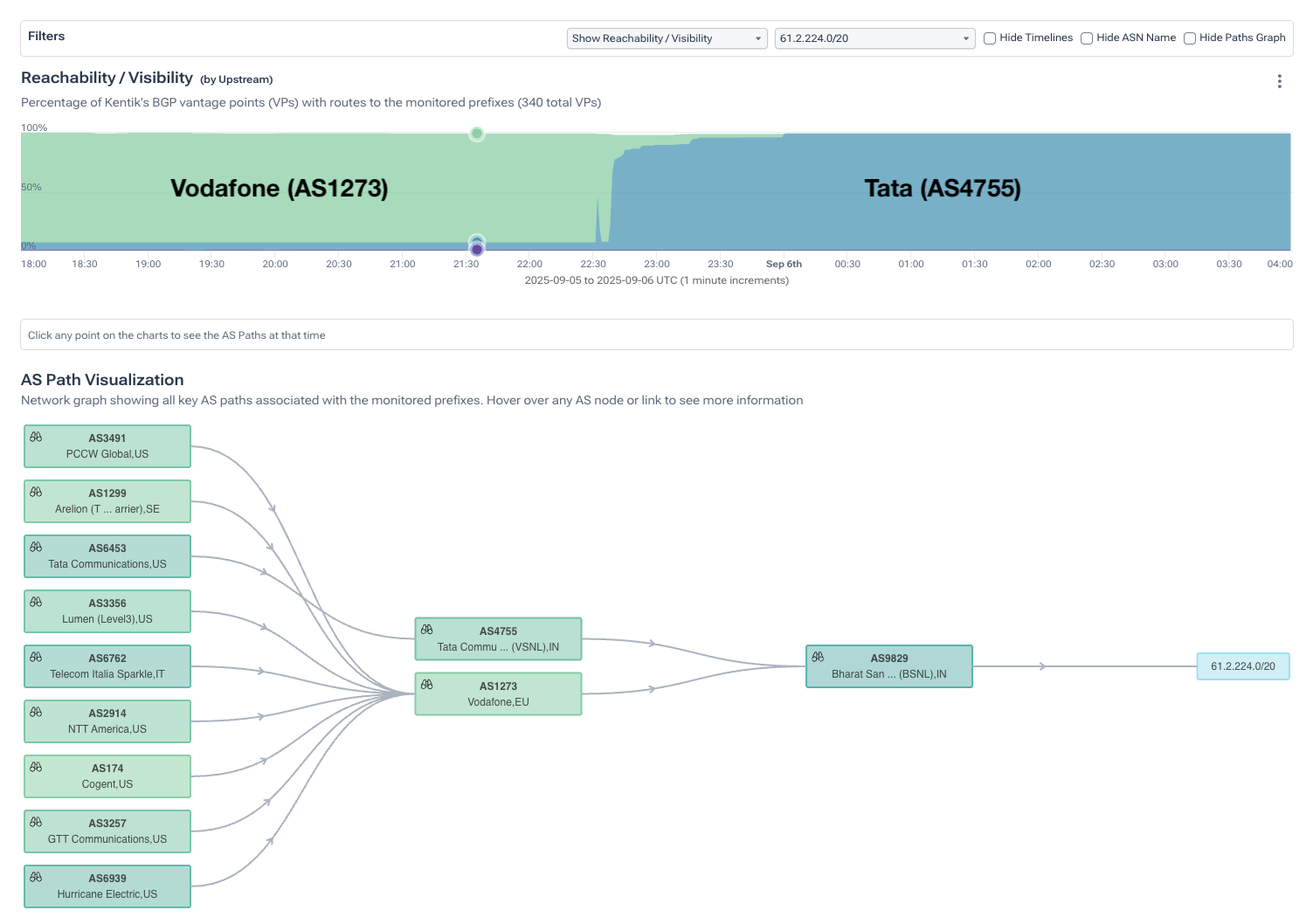

BNSL (AS9829) lost transit from Vodafone (AS1273), GTT (AS3257), and Tata (AS6453) as a result of the cable cuts. The BGP visualization below shows one route (61.2.224.0/20), originated by AS9829, switching from AS1273 transit to AS4755 at 22:32 UTC, like in the previous example.

Conclusion

Despite multiple submarine cable cuts in the Red Sea, traffic is still flowing between Europe and Asia. Numerous major cables continue to operate along this route completely unscathed, including SMW-5, AAE-1, and PEACE cables. As a result, the overall impact to traffic levels in affected countries has been subtle, primarily manifested as the loss of a subset of transit options for regional providers.

As is often the case with submarine cable incidents, there’s been no public communication directly from the cable operators themselves. As a result, an information vacuum forms and gets filled with rumors and conspiracies, which are unhelpful to improving the public’s understanding of incidents like these and what people should think about them.

Additionally, that vacuum causes a company like Microsoft to be essentially punished for its responsible communication, while its competitors avoid bad press by remaining silent about the real impacts of the cable cuts on their operations.

Earlier this year, the South China Morning Post published an alarming story about a new Chinese submarine cable cutter that “could reset the world order” due to its ability to sever deep-sea submarine cables. Upon further inspection, the cable cutter at the center of the story was actually a standard cut-and-hold grapnel that has been standard equipment in the cable repair and maintenance industry for decades.

If we have any hope to improve the public’s understanding about the role submarine cables play and how to better protect them from damage, accidental or otherwise, we’ll need better engagement from the submarine cable operators or the ICPC when these major cable cuts take place.