Iraq Blocks Telegram, Leaks Blackhole BGP Routes

Summary

This past weekend, the government of Iraq blocked the popular messaging app Telegram, citing the need to protect Iraqi’s personal data. However, when an Iraqi government network leaked out a BGP hijack used for the block, it became yet another BGP incident that was both intentional, but also accidental. Thankfully disruption was minimized by Telegram’s use of RPKI.

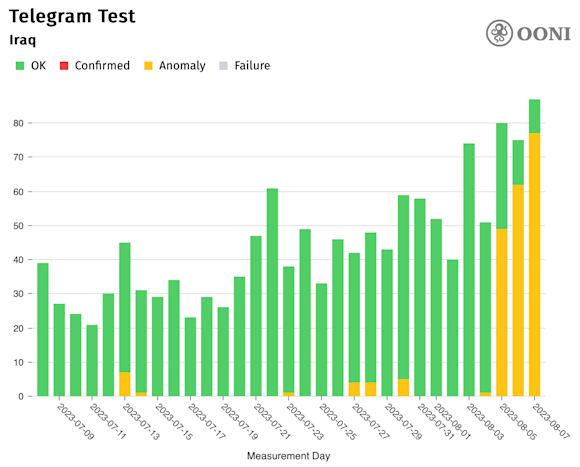

This past weekend, the government of Iraq took the step to block the popular messaging app Telegram, citing the need to protect the personal data of Iraqi users following a leak of confidential information. According to data from our friends over at Tor’s Open Observatory for Network Interference (OONI), the block was implemented by blocking Telegram’s IP addresses.

Evidently, when the Iraqi government began blocking Telegram, it started by using BGP to hijack traffic destined for IP addresses associated with the messaging service, redirecting them to the proverbial bitbucket. And, as has happened before on numerous occasions, these hijack BGP routes leaked out of the country.

However, despite this technical error, no Telegram disruption was reported outside of Iraq, in part, due to the fact that Telegram had created Route Origin Authorizations (ROAs) for its routes allowing ASes outside of Iraq to automatically reject the hijacks. A ROA is a record in RPKI that specifies the AS origin that is authorized to originate the IP address range.

Intentional, but also accidental

Perhaps the most famous BGP hijack ever was Pakistan’s hijack of YouTube in 2008 (also see The Internet’s Biggest BGP Incidents). In that case, the Pakistani government ordered a block of Youtube in the country. The Pakistani state telecom, PTCL created BGP routes to hijack traffic destined for Youtube and blackhole it. However, the hijacks leaked out of Pakistan, leading to a global disruption of Youtube. Over the years, there have been many such leaks of BGP hijacks meant to censor content, such as those in Ukraine and Iran.

More recently, during the initial weeks of the Myanmar military coup in 2021, the military junta in charge ordered social media to be blocked. To comply with the order, one Myanma ISP elected to use BGP in order to hijack local Twitter traffic and drop it. Unfortunately, their hijack route was inadvertently leaked out of Myanmar, causing disruptions to Twitter around South Asia.

And finally, last year, during Russia’s crackdown on social media and independent journalism following their invasion of Ukraine, a Russian ISP elected to use BGP to blackhole traffic to Twitter by hijacking the exact same prefix (104.244.42.0/24) that was hijacked a year earlier in Myanmar.

However, there was a difference between the two hijacks of Twitter’s 104.244.42.0/24 by Myanmar in 2021 and then again by Russia in 2022. In the intervening year, Twitter deployed RPKI, creating ROAs in RPKI for nearly all of its routes. By doing so, it enabled ASes which reject RPKI-invalid routes to automatically reject the hijack routes, limiting the disruption to Twitter.

As Twitter’s CISO wrote at the time, “a bunch of the point of having security is to keep your systems from breaking all of the time” and in this case, it kept a BGP hijack from breaking access to Twitter for users outside of Russia. The Russian hijack propagated slightly less than the hijack from Myanmar, but it is hard to directly compare since the hijacks were announced from different places on the internet, and there are numerous factors which can influence BGP route propagation.

Anecdotally, I would say that after my NANOG 86 presentation on the internet impacts due to the war in Ukraine, one of Twitter’s network engineers shared that, from a traffic standpoint, they observed significantly less disruption due to the Russian hijack. They believed the difference was due to RPKI.

The recent episode in Iraq is similar to the aforementioned cases because it was a BGP incident that was intentional, but also accidental. The network accidentally leaked out a BGP hijack that they intentionally created.

The hijacks from Iraq

Except for the networks in the semi-autonomous region of Kurdistan, all Iraqi internet service must go through AS208293, a government network which serves as the country’s international gateway. AS208293 normally doesn’t originate any routes; it only connects the country’s telecoms to international transit providers.

However, at 13:52 UTC on 5 August 2023, AS208293 started originating the following prefixes:

| 151.106.160.0/19 | 95.161.64.0/20 |

| 95.161.0.0/17 | 91.108.8.0/22 |

| 91.108.0.0/18 | 91.108.4.0/22 |

| 149.154.160.0/20 | 149.154.164.0/22 |

| 91.108.56.0/22 | 149.154.160.0/22 |

All but the first are address ranges used by Telegram. 151.106.160.0/19 was last utilized by the now-defunct Subspace network, so the reason for its inclusion is unclear.

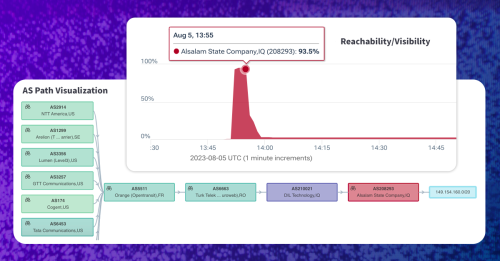

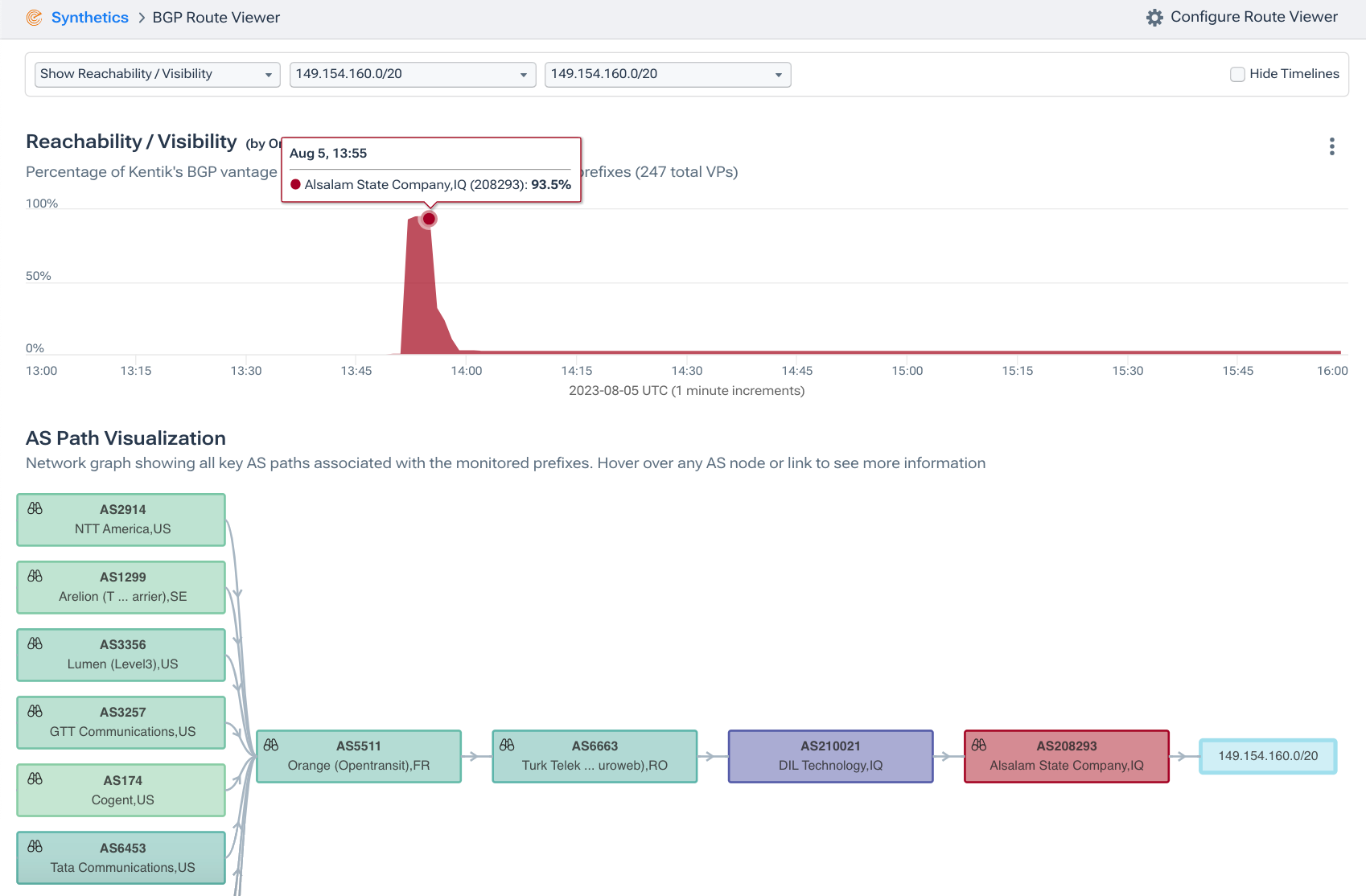

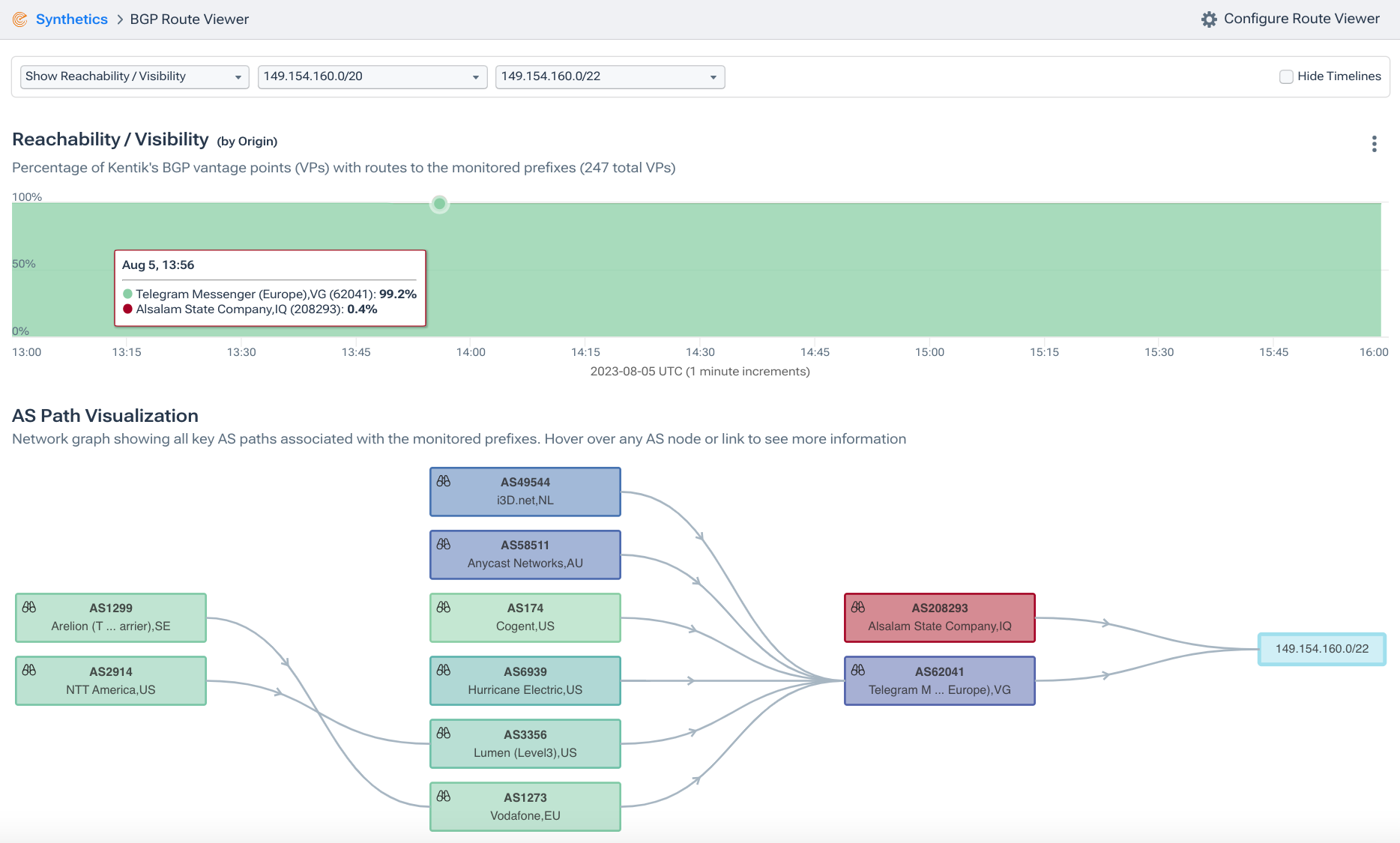

Illustrated in Kentik’s BGP Route Viewer below, 149.154.160.0/20 was originated by AS208293 and attained global circulation for two reasons. The first was that there was no competing route in circulation — 149.154.160.0/20 is “less-specific” to existing Telegram routes. Secondly, there was no matching ROA in RPKI to give ASes who have deployed RPKI a reason to reject it.

Conversely, when we look at the propagation of the corresponding “more-specific” 149.154.160.0/22, we see that nearly the entire internet believed (correctly!) that AS62041 (Telegram) was the origin. While AS208293 shows up in red in the ball-and-stick diagram along the bottom, it can hardly be seen in the upper stacked plot, which depicts route propagation by origin.

The lack of propagation of a BGP route with AS208293 as the origin of 149.154.160.0/22 is due to the fact that there was already an existing route to compete with (originated by AS62041), but also because the route from Iraq was RPKI-invalid, dramatically limiting its reach.

Conclusion

The challenge of measuring the positive impact of any security mechanism is that it often requires knowledge of the incidents that didn’t occur as a result of its use. RPKI is no different. While it likely didn’t have the potential to be another Pakistan/YouTube incident, BGP non-events like this are what RPKI success looks like.

Of course, this is little solace to the Iraqi users who must now employ a VPN to circumvent this IP-level blockage. Censoring Telegram will do little to protect the personal data of any Iraqis, but it does cut them off from a popular communication tool and source of news and information.