From Stealth Blackout to Whitelisting: Inside the Iranian Shutdown

Summary

Iran is in the midst of one of the world’s most severe communications blackouts. This post uses Kentik data to detail how this historic event unfolded, where this event lies in the context of previous Iranian shutdowns, and finally discusses what might be in store next for Iran.

For nearly two weeks, Iran has been enduring one of the most severe internet shutdowns in modern history. The theocratic regime’s decision to restrict communications coincided with a violent nationwide crackdown on a growing protest movement driven by worsening economic hardship.

In this post, I explore the situation in Iran using Kentik’s aggregate NetFlow data, along with other sources.

The big picture

At the time of this writing, a near-complete internet shutdown has persisted for almost 14 days. Along with internet services, international voice calling has also been blocked (there have been a couple of periods when limited outgoing calls were allowed), and domestic communication services have experienced extended disruptions, including Iran’s National Information Network. For a country of 90 million people, the combined blocking of these communication modes makes this blackout one of the most severe in history.

To learn more about the conditions that lead to the check out this special episode of Kentik’s Telemetry Now podcast with Iranian digital rights expert Amir Rashidi, Director of Digital Rights and Security at the human rights organization Miaan Group:

Some background first

For decades, the internet of Iran has been connected to the world via two international gateways:

- Telecommunication Infrastructure Company (TIC) (AS49666, previously AS12880, AS48159)

- Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences (IPM) (AS6736)

IPM, primarily a university and research network, was the country’s original internet connection in the 1990s, a story covered in the excellent book The Internet of Elsewhere by Cyrus Farivar. Years later, the state telecom TIC got into the business of providing internet service and today handles the vast majority of internet traffic into and out of Iran.

Despite TIC’s dominance, IPM has maintained a technologically independent connection to the outside world, though it has never been immune from Iranian government censorship and surveillance. This distinction matters because each gateway behaved differently during the shutdown.

January 8, 2026

In the days leading up to January 8, there were many reports of localized internet blockages around the country, but these incidents weren’t big enough to register on any of our national traffic statistics for Iran.

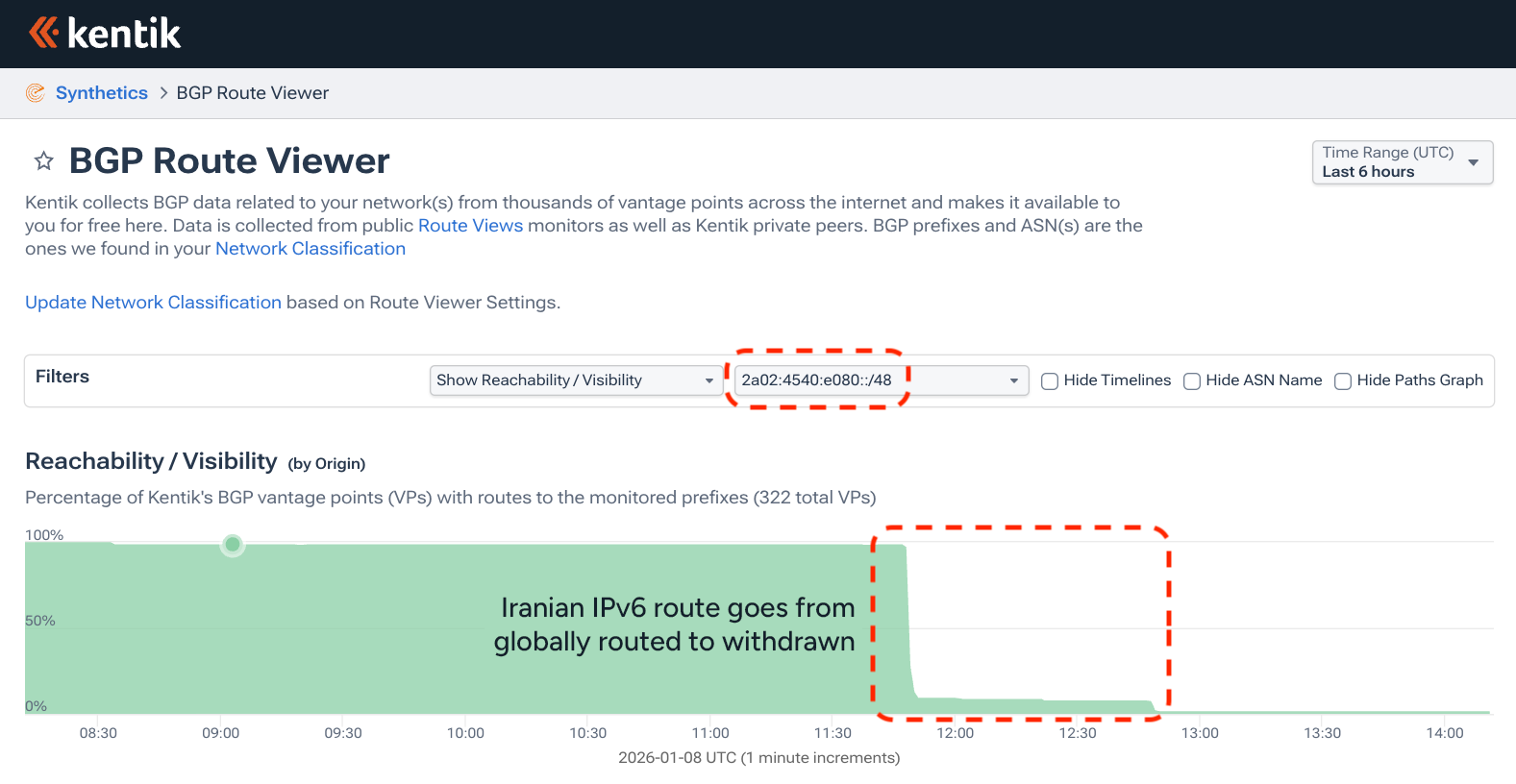

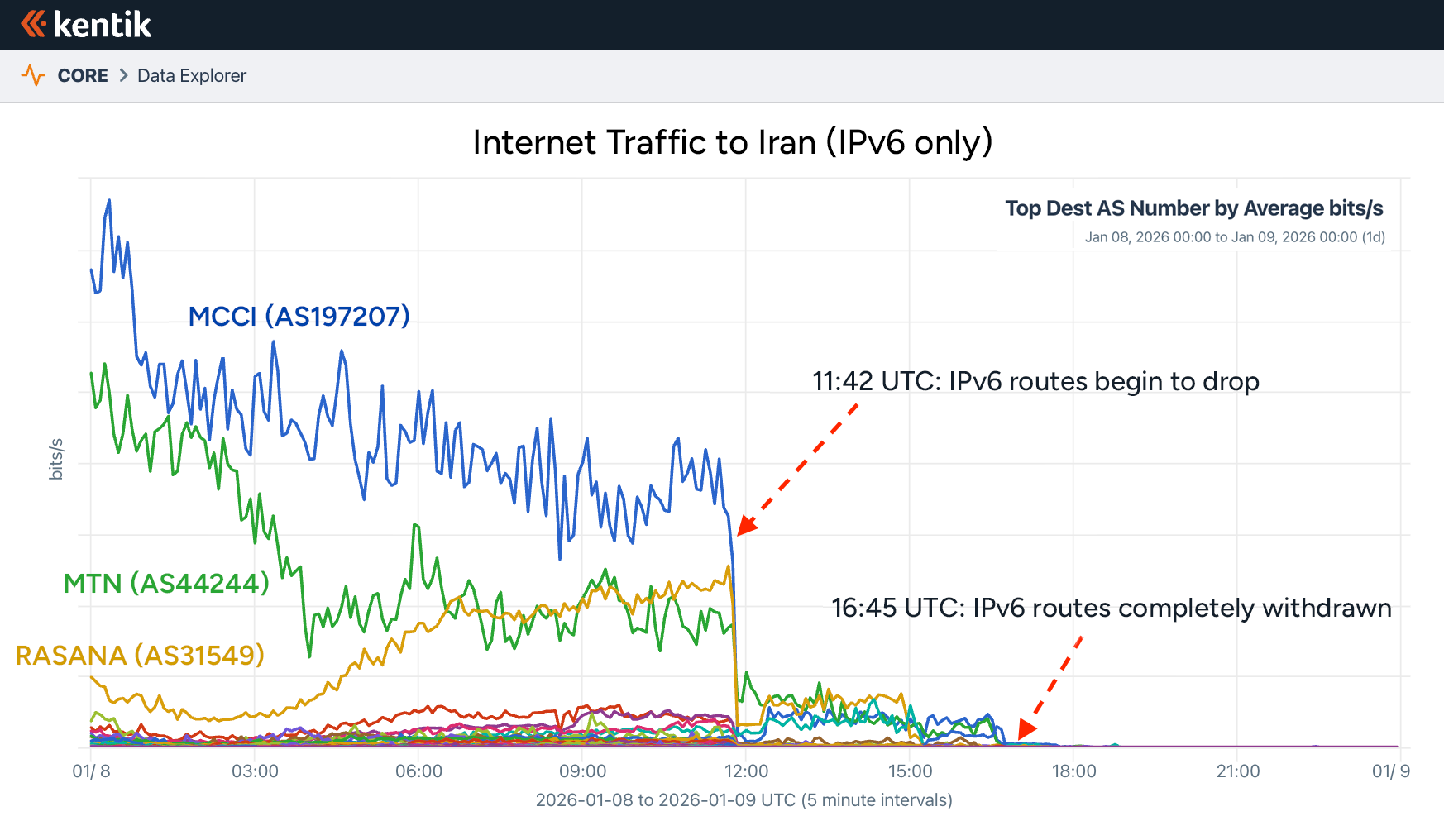

The first major development occurred at 11:42 UTC on January 8, 2026, when TIC (AS49666) began withdrawing its IPv6 BGP routes from its sessions with other networks. Within hours, nearly all of Iran’s IPv6 routing had disappeared from the global routing table.

From our perspective, this is what IPv6 traffic to Iran looked like on January 8.

However, based on our aggregate NetFlow, IPv6 traffic normally amounts to less than 1% of the overall traffic (in bits/sec) into Iran, so the average Iranian was unlikely to be affected by this issue. Regardless, the withdrawal of IPv6 routes appeared to be an early indication of what was to come later in the day.

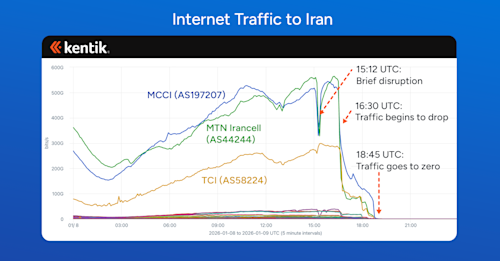

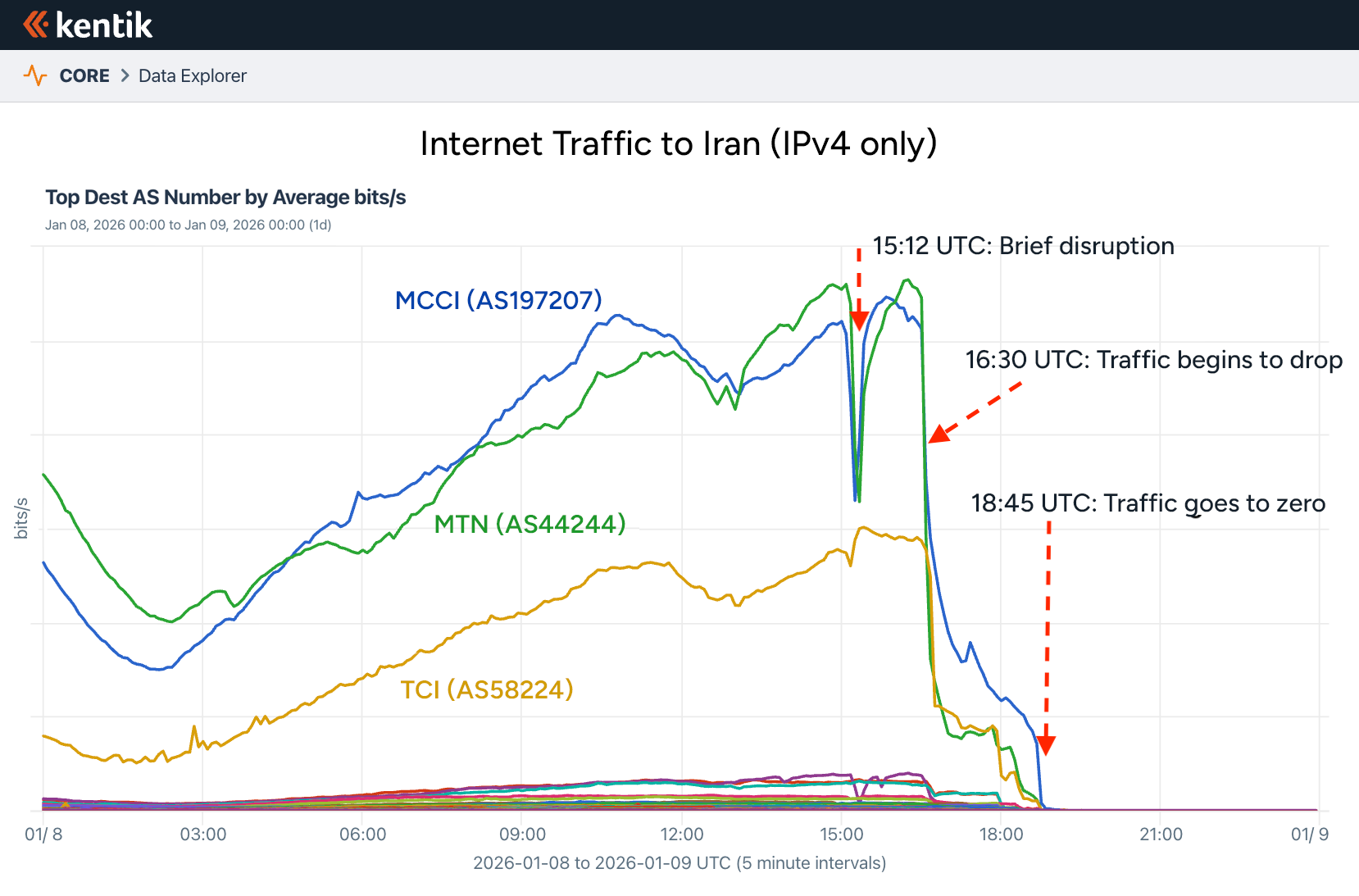

Following a brief disruption, we observed internet traffic levels begin to plummet at 16:30 UTC (7pm local). The drop continued until internet traffic into Iran had all but ceased by 1845 UTC, as illustrated below. It took over two hours to stop all internet traffic into and out of the country.

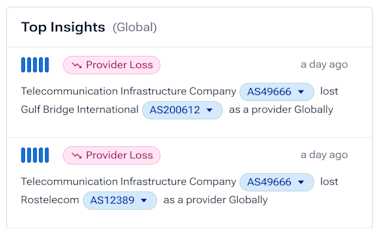

At 19:00 UTC, we observed TIC disconnecting from a subset of its transit providers, including Russian state telecom Rostelecom (AS12389) and regional operator Gulf Bridge International (AS200612), and all of its settlement-free peers.

Despite the loss of numerous BGP adjacencies for AS49666 (TIC), the vast majority of Iranian IPv4 routes continued to be routed globally. The drop in Iranian IPv4 traffic, therefore, could not be explained by reachability issues; another mechanism was at work at the network edge blocking traffic.

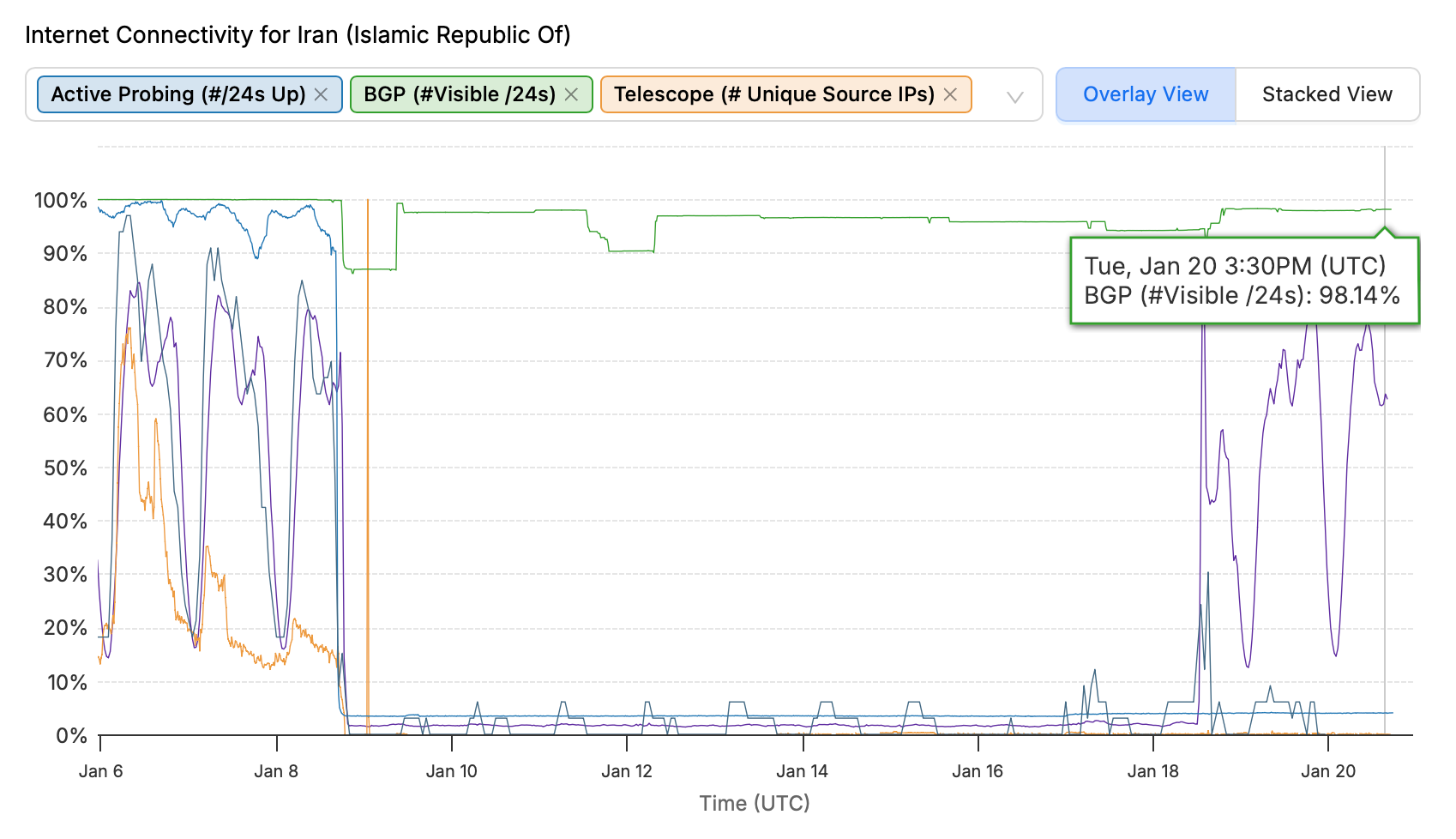

Georgia Tech’s IODA tool captures this divergence well. In the below screenshot, active probing (blue) drops to zero as traffic is blocked, while routed IPv4 space in BGP (green) is almost completely unscathed (98.14%).

Although IPv4 routes remained online, internet traffic stopped for roughly 90 million Iranians. This distinction is central to Iran’s next step: internet “whitelisting,” in which an Iranian version of the Chinese Great Firewall allows only approved users or services while blocking all others. Had authorities withdrawn IPv4 routes, as they did with IPv6, Iran would have become completely unreachable, as Egypt was in January 2011. By keeping IPv4 routes in circulation, Iranian authorities can selectively grant full internet access to specific users while denying it to the broader population.

Limited connectivity

As mentioned above, the internet shutdown in Iran is not complete. There has been a tiny amount of traffic still trickling in and out as a small set of Iranians continue to enjoy internet access.

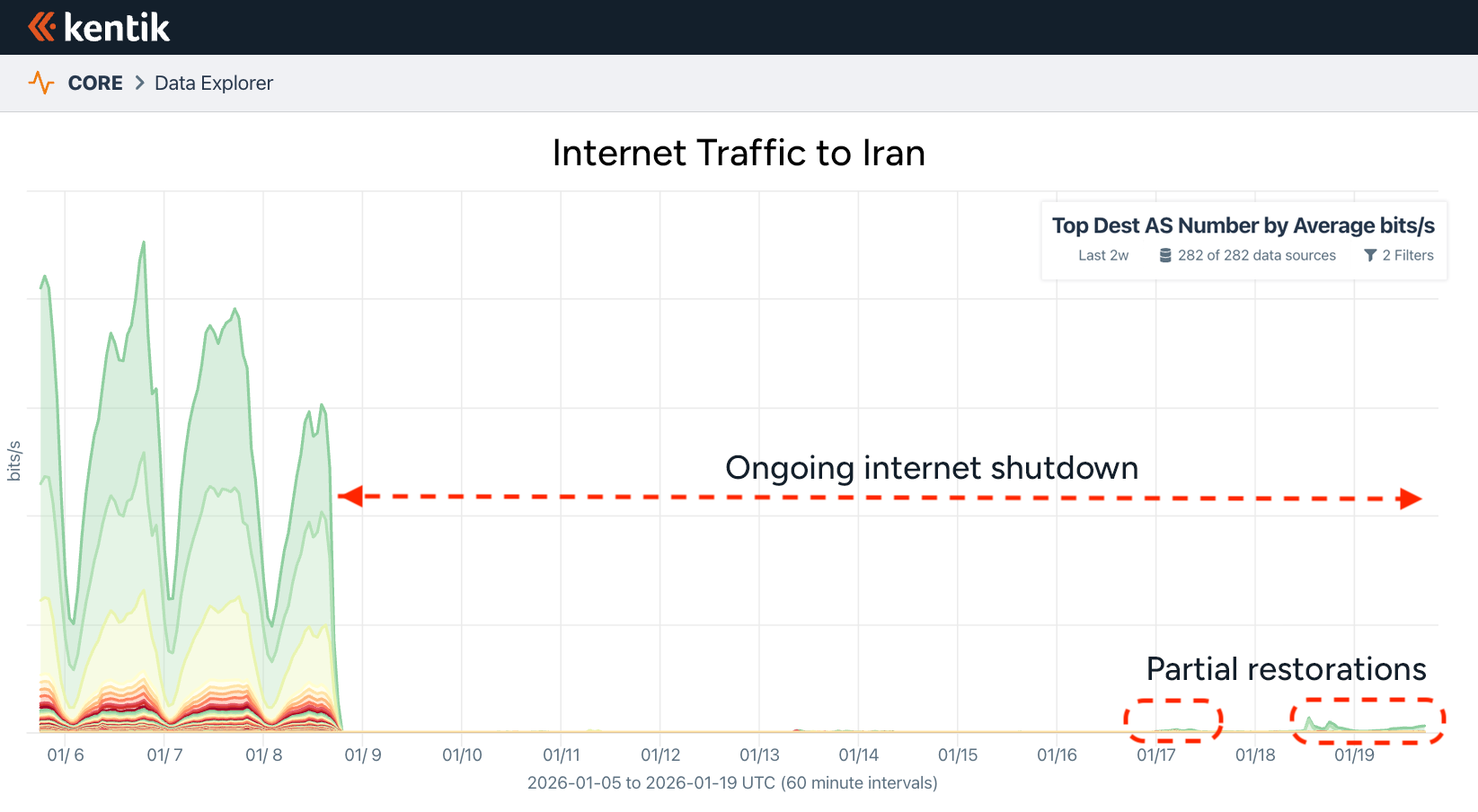

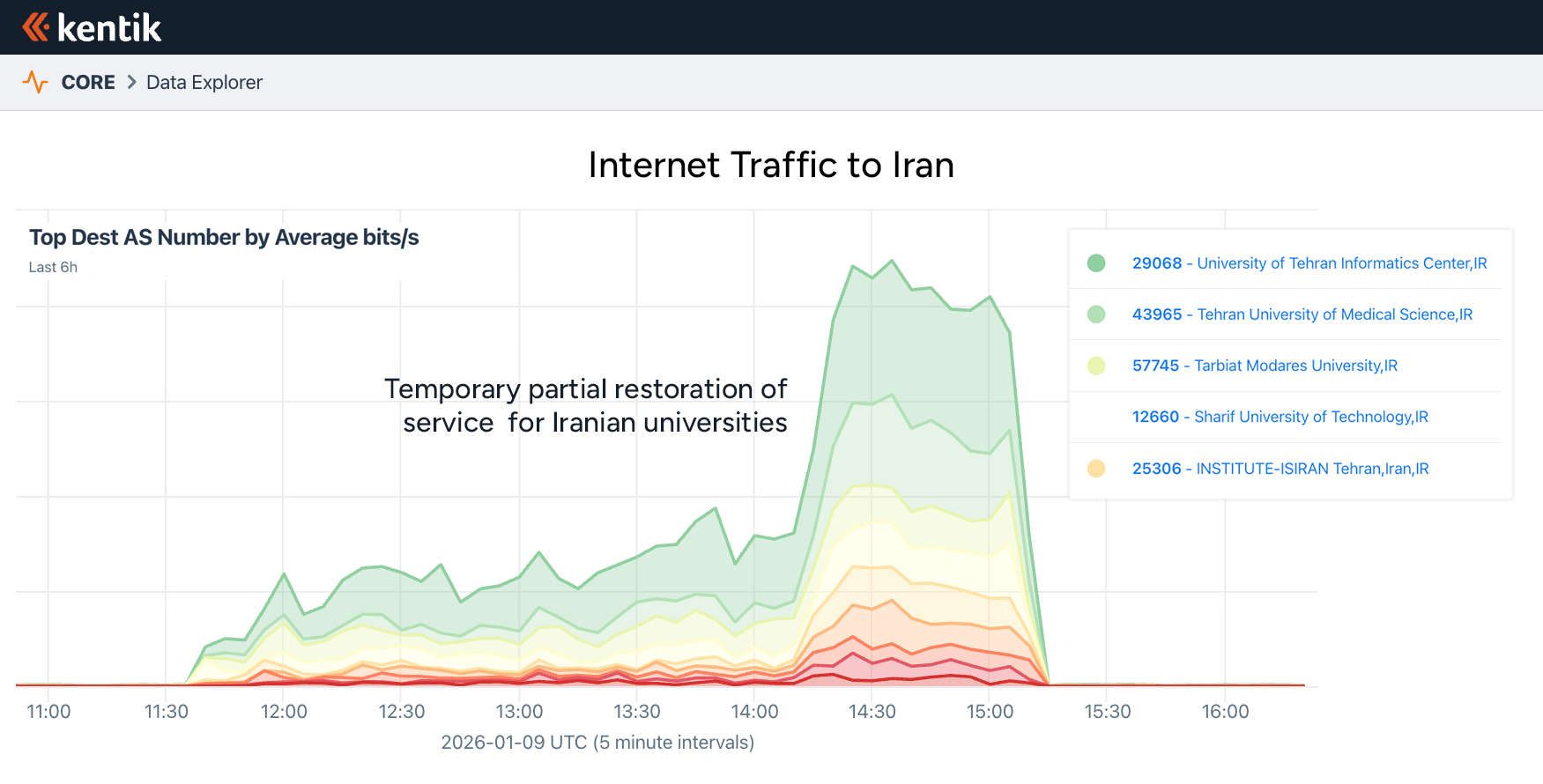

There have also been a few temporary partial restorations of service, such as a multi-hour restoration of service to Iranian universities via AS6736 on January 9th, and a more recent small surge in traffic.

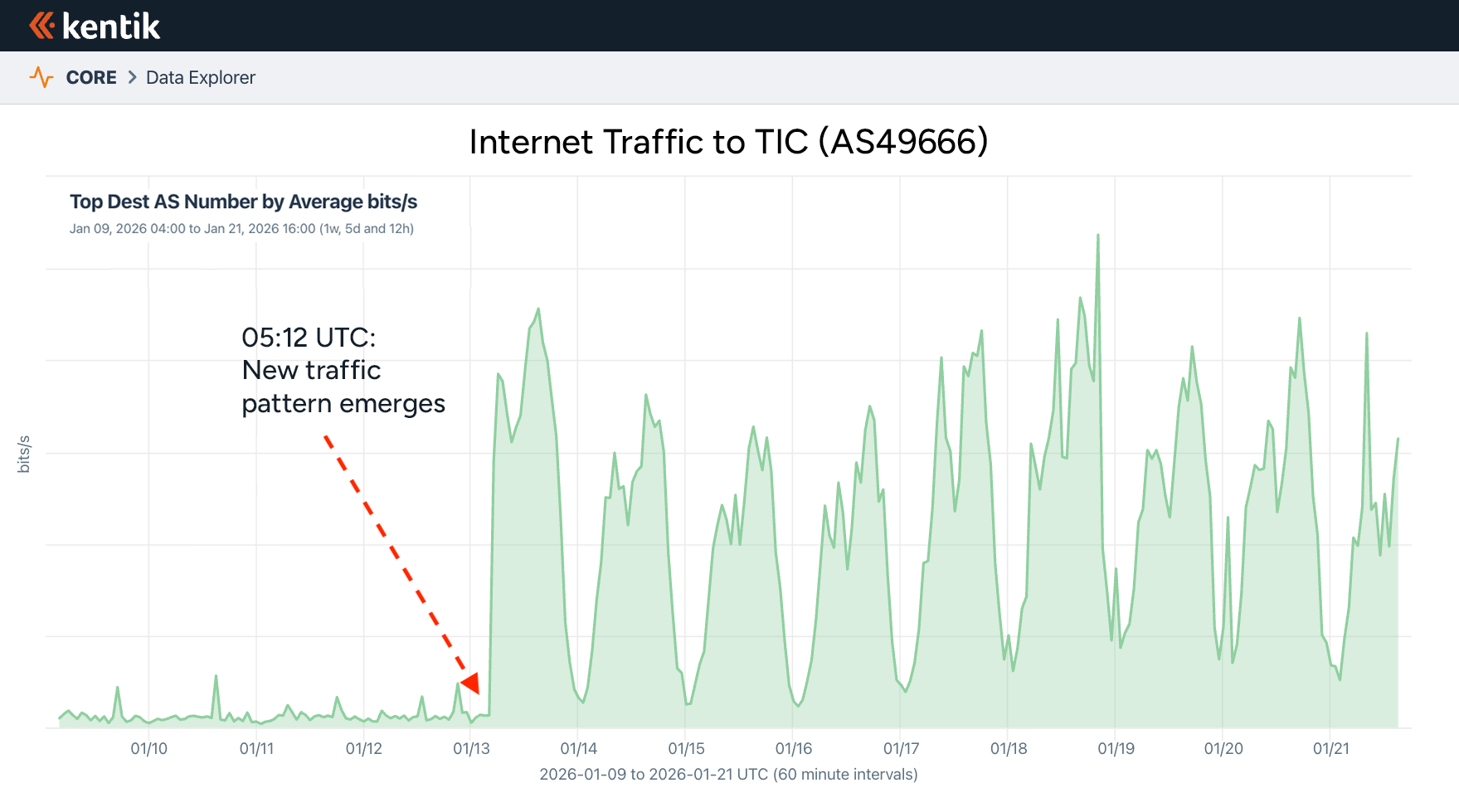

From our data, we have also observed the emergence of a diurnal pattern of traffic to AS49666 emerge on January 13. AS49666 is not typically a major terminus for internet traffic to Iran, so this traffic is likely proxied traffic from whitelisted individuals or services.

As of late, we’ve seen a few measures like the restoration of transit from Rostelecom and the return of routes originated by IPM, as the country appears to be moving towards a partial restoration. At the time of this writing, the plan appears to be to operate the Iranian internet as a whitelisted network indefinitely.

Evolving calculus of shutdowns in Iran

Back in 2012, Iran was in the beginning stages of building its National Information Network (NIN), ostensibly built to allow the country to continue to function in the event that it was cut off from the outside world. At the time, I teamed up with Iran researcher Collin Anderson to investigate. With access to in-country servers, we mapped Iran’s national internet from the inside (research published here).

We found that the NIN had been implemented by routing RFC1918 address space (specifically 10.x.x.x) between Iranian ASes within the country. By doing so, they could be assured that devices connected to the NIN would not be able to receive connections from the outside world, as those IP addresses are not routable on the public internet.

In 2019, I reported on Iran’s internet shutdown following the government’s decision to raise gas prices. At the time, it was the most severe shutdown in the country’s history—until this month. It involved withdrawing BGP routes of some networks while blocking traffic of others, and lasted for almost two weeks.

Government-directed shutdowns in Cuba and Iran in 2022 led me to join up with Peter Micek of the digital rights NGO Access Now to write a blog post that traced the history and logic behind “internet curfews,” a tactic of communication suppression in which internet service is temporarily blocked on a recurring basis.

The article described internet curfews as another means of reducing the costs of shutdowns, not unlike the development of the NIN, according to Iranian digital rights expert Amir Rashidi. In that post, we wrote:

The objective of internet curfews, like Iran’s NIN, is to reduce the cost of shutdowns on the authorities that order them. By reducing the costs of these shutdowns, they become a more palatable option for an embattled leader and, therefore, are likely to continue in the future.

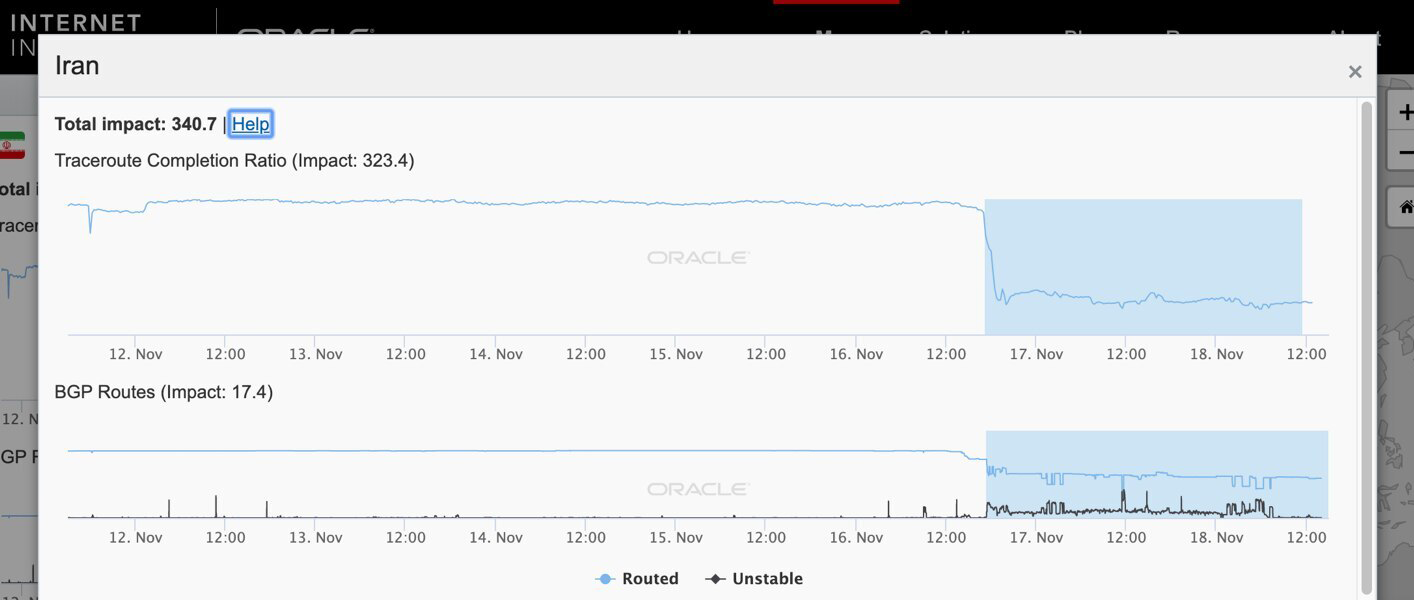

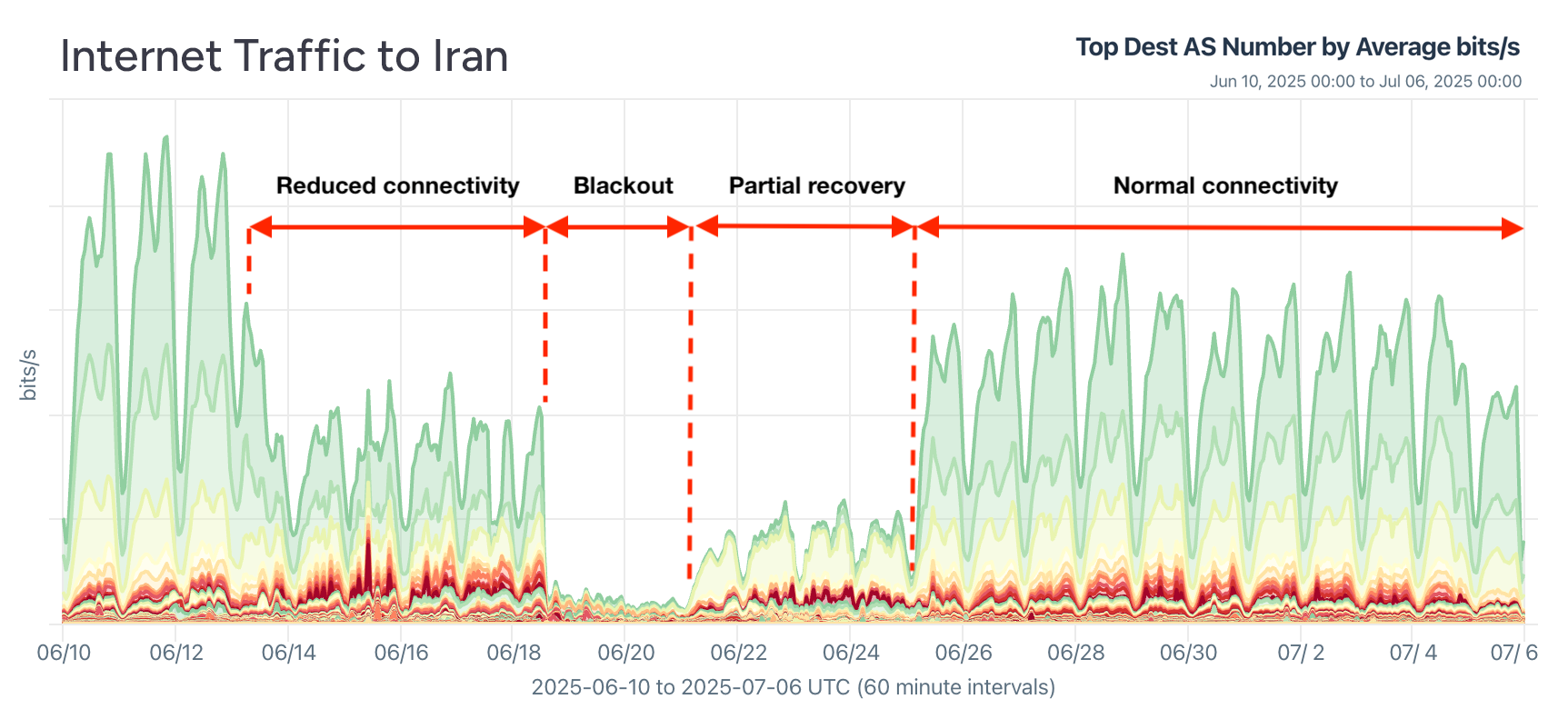

During the Twelve-Day War between Israel and Iran this June, Iran partially or fully shut down its internet, ostensibly to defend against cyberattacks and drone strikes. We, along with other internet observers, documented the shutdown’s phases and contributed to a detailed report by Rashidi’s team, which dubbed the shutdown as a “stealth blackout” due to the fact that traffic was disrupted without withdrawing any BGP routes.

The outage demonstrated Iran’s newfound ability to block traffic nationwide without manipulating BGP routes, signaling a higher level of sophistication in its internet filtering. This summer’s Stealth Blackout ultimately foreshadowed the ongoing shutdown Iran is now enduring.

Help from above

In the aftermath of the 2022 protests, Starlink began allowing connections from Iran. Satellite internet operators like Starlink must typically clear, at a minimum, two legal hurdles to operate in a country: a telecom license and radio spectrum authorization from the local government. Starlink has been operational in Iran for over three years at this point without either, and the Iranian government has taken note.

The ITU Radio Regulations Board (RRB) is a quasi-judicial United Nations body that interprets and applies the Radio Regulations, to include satellite emissions. It exists to resolve disputes between countries and oversees compliance with the international radio frequency register, but, in the end, has no direct enforcement power.

Since 2023, the Iranian has been pleading their case to the ITU that the Starlink service in Iran needed to be disabled. The 100th meeting of the ITU RRB took place in November, and on the topic of Starlink, the board decided to:

- “Request the Administration of the Islamic Republic of Iran to pursue its efforts, to the extent possible, to identify and deactivate unauthorized STARLINK terminals in its territory,

- Strongly urge the Administration of Norway to take all appropriate actions at its disposal to have the operator of the Starlink system immediately disable unauthorized transmissions of its terminals within the territory of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

Regardless of the decisions of this body, Starlink continues to operate in the country. (Note: The US and Norway share responsibility for Starlink’s ITU registration.)

Despite a recent Iranian law that would equate the use of Starlink with espionage, punishable by death, Iranian digital rights activists have been working for years to smuggle in terminals and build communication infrastructure to extend the internet services within the country. The recent front-page New York Times article I collaborated on described these efforts, which now must contend with a novel form of jamming Starlink service in some urban areas of Iran.

Other governments are watching, learning

In the decade and a half since the internet shutdowns of the Arab Spring, we’ve observed the practice of suppressing communications evolve as authoritarian governments learn tactics from one another. In the ongoing shutdown in Iran, multiple such tactics are on display.

To mitigate the costs of its shutdown, the Iranian government has created an internal national internet and appears to be in the process of building a “whitelisting” system to allow certain individuals and services internet access while blocking the rest. If these measures successfully enable an unpopular Iranian government to remain in power, we can expect to see them replicated elsewhere.

On the other side, the digital rights activists have also been building tools, funded in large part by the now-embattled Open Technology Fund, to allow communications to continue during a shutdown like this. However, no amount of circumvention tooling can restore service to 90 million people.

The fight for open and free communications does not have an end. As long as authoritarian governments exist, this game of cat-and-mouse will continue. Ours is only to decide which side we’re on and to throw our support (financially and otherwise) to those working on solutions to these problems.