Cloud Observer: Subsea Cable Maintenance Impacts Cloud Connectivity

Summary

In this edition of the Cloud Observer, we dig into the impacts of recent submarine cable maintenance on intercontinental cloud connectivity and call for the greater transparency from the submarine cable industry about incidents which cause critical cables to be taken out of service.

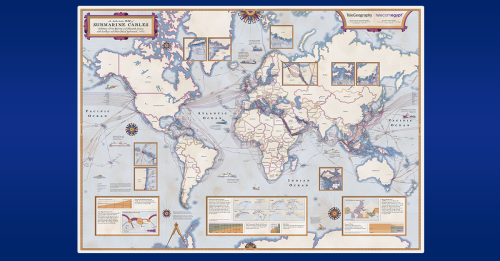

In recent weeks, two of the internet’s major submarine cable systems were down for repairs, impacting internet traffic between Europe and Asia. As we’ve pointed out in the past, the major public clouds rely on the same submarine cable infrastructure as us regular internet users, so when a cable incident occurs, cloud connectivity is also affected.

In this edition of the Cloud Observer, we’ll take a look at what we observed when Sea-Me-We-5 (SMW-5) and IMEWE were recently down for repairs.

Cloud synthetic measurements

The Cloud Observer is a recurring series focused on analyzing inter-regional cloud connectivity. These posts utilize Kentik’s continuous measurements between our agents in over 110 cloud regions in the world’s largest cloud providers: AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud. Configured in a full mesh, these agents perform ping and traceroute tests to every other agent providing a continuous picture of interconnectivity within the cloud.

SMW-5 downtime

Sea-Me-We-5’s name is an acronym that traces the geographic path the cable takes: Southeast Asia (SEA), Middle East (ME), Western Europe (WE). It was designated as ‘ready for service’ (RFS) in 2016 and is the fifth edition of a consortium-owned intercontinental submarine fiber optic cable carrying a large portion of the internet traffic between Europe and Asia.

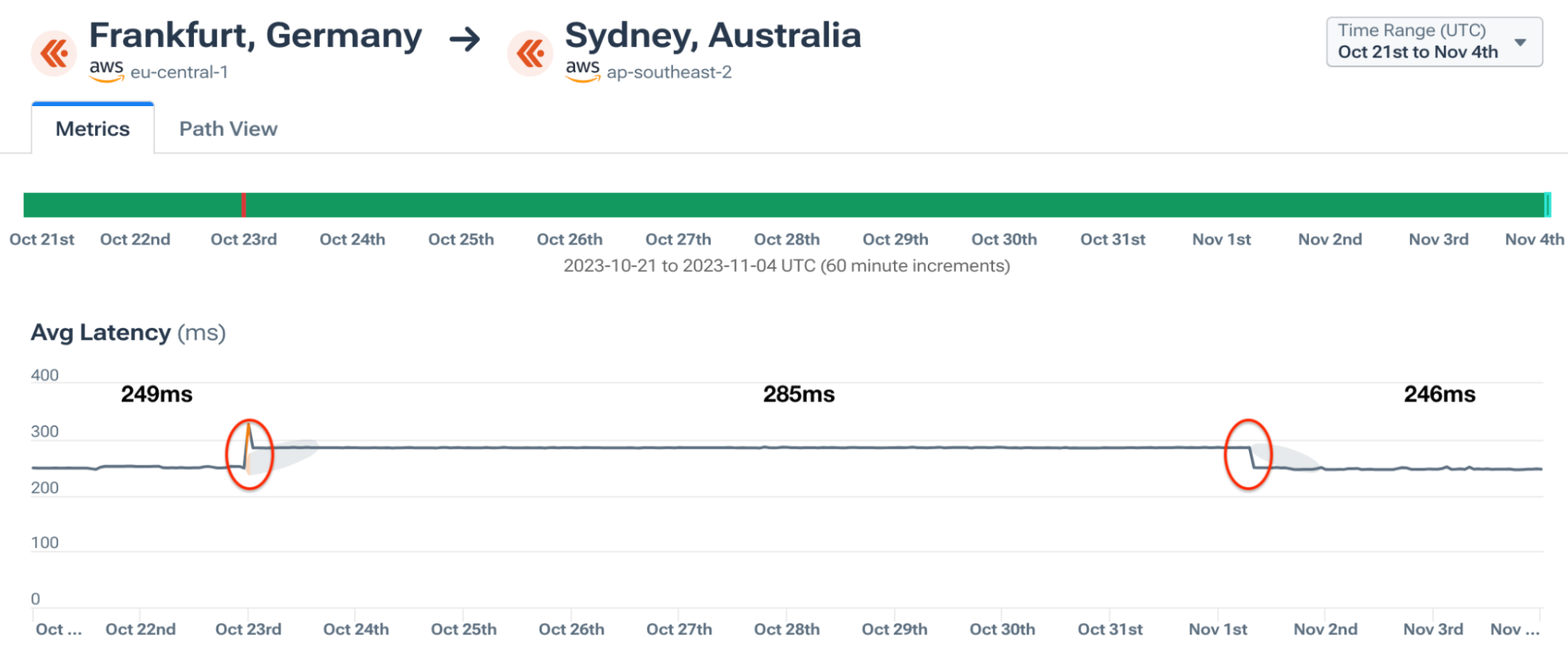

As I described in a brief post last month, at 00:00 UTC on October 23, SMW-5, the major submarine cable connecting Asia to Europe, was taken down to repair a shunt fault. A shunt fault occurs when sea water breaches the cable’s insulation, causing a short circuit in the cable’s electrical feed.

Submarine cables contain an electrical system that carries thousands of volts of electricity to power the amplifiers (often referred to as repeaters) that are placed every 70 km or so to maintain signal strength. Normally, a cable can continue operating despite suffering a shunt fault, but must be repaired as soon as possible.

My friend Philippe Devaux describes himself as “a keen observer of the global submarine cable systems industry” and has a knack for piercing through the secretive world of submarine cables (occasionally reaching the ship crews themselves) to find insiders willing to confirm details of submarine cable repairs.

In a recent LinkedIn post for the SMW-5 repairs, he identified the cable ship (CS) Asean Restorer as the vessel performing the repairs of the shunt fault disrupting Europe-to-Asia internet traffic.

The loss of the major route between Asia and Europe was picked up on the latency measurements between our agents in cloud regions. Numerous routes experienced latency increases of around 40 ms. The criticality of SMW-5 was evident as all three major public clouds experienced latency changes due to the loss of the cable. Let’s take a look at some of the impacts caught in Kentik’s cloud measurements.

Amazon Web Services

Google Cloud

Azure

The impacts for AWS and GCP revealed a stable shift in latency, likely owing to a longer geographic path while SMW-5 was undergoing repairs. Alternatively, the measurements involving the Azure regions showed periodic latency increases that align with work days, as pictured below. This may suggest that Azure would shift a portion of its traffic to a longer path only during busy working hours.

And, of course, it wouldn’t be a submarine cable analysis without providing an example of a case when latencies improved due to the loss of a submarine cable. The graphic below illustrates the impact of the loss of SMW-5 on the latencies from AWS’s eu-west-3 in Paris to Azure’s uaenorth in Dubai — a drop from 114ms to 90ms.

Why would latency drop as a result of the loss of a submarine cable? I addressed this in my blog post from August about the submarine cable cuts off the west coast of Africa:

While this may seem counterintuitive, this is a phenomenon I have often encountered when analyzing submarine cable cuts... Essentially a higher latency route becomes unavailable, and traffic is forced to go a more direct path. Why would traffic be using the higher latency path in the first place? What you can’t see in these visualizations are factors like cost.

In that example, latencies between Cape Town and Seoul dropped when the WACS cable was cut and AWS had to redirect traffic over a more direct path through the Indian Ocean. In that case, there simply may not be a business case to justify paying a premium to ensure the lowest latency between those two distant locations.

That logic would seem to hold less weight in the case of latencies between Dubai and Paris. Network engineers in the Middle East typically try to optimize latencies to Europe, the main source of global transit for the region. In this case, we’re looking at a traffic handoff between two clouds (AWS and Azure). As we will explore in future posts in this series, it is not uncommon to find suboptimal latencies between two clouds each operated by a different networking team with its own interconnection strategy.

IMEWE downtime

Similar to SMW-5, IMEWE’s name derives from its route, heading east to west: India (I), Middle East (ME), Western Europe (WE) and was RFS in 2010. In a talk I gave at MENOG in Muscat, Oman in 2011, I presented evidence of IMEWE’s activation for the country of Lebanon.

In a LinkedIn post, Phillippe Devaux again identified the vessel performing the repair as the cable ship (CS) Maram, presently in the Gulf of Aden. Phillippe added:

CS Maram departed Salalah 27OCT23, currently positioned about 60km off Aden, where she has been mostly stationary since 03NOV23, likely busy repairing IMEWE fault. (ETR Expected Time to Repair: 12NOV23)

We could see the impacts of this cable maintenance in a couple of places in our tools. Latency between AWS’s eu-south-1 in Milan and me-south-1 in Manama, Bahrain, dropped by 31ms during the IMEWE outage.

Additionally, Kentik Market Intelligence (KMI) reported impacts, including the loss and subsequent return of transit from Telecom Italia Sparkle (AS6762) for Pakistani incumbent PTCL (AS17557).

Below is a visualization from transit data from KMI over time showing the disappearance of AS6762 in peach on November 2nd, followed by an increase in transit from TMnet (AS4788 in maroon) before seeing a return of AS6762 transit for AS17557 on the 10th.

Incidentally, I have a connection to the cable ship performing this repair. At a submarine cable conference in 2016, the event provided a tour of the newly christened CS Maram docked in Dubai. Below is a picture of me in the bay of the CS Maram in front of a QTrencher 400, a massive remotely operated vehicle (ROV) for subsea trenching and cable maintenance.

A call to action

Submarine cables require regular maintenance and repair, and as I mentioned in my post about the submarine cable cuts in Africa: the seafloor can be a dangerous place for cables.

The loss of submarine cable connectivity can have profound impacts on the international flow of internet traffic, but unfortunately, the submarine cable industry isn’t communicative to the general public on events like this, and this is a problem. Typically, cable operators only report downtime and outages to their direct customers. If those customers fail to notify a broader audience, the general public is left to speculate on the causes of internet outages.

In 2017, I wrote a blog post about Telecom Heroics in Somalia, which told the story of how the ISPs in Mogadishu faced down a terrorist threat to activate their first submarine cable landing. In that piece, I also covered an incident where the lack of communication from a cable operator could have gotten people hurt.

Somalia held a presidential election earlier this year, and as the candidates were getting ready for their first nationally televised debate, the country’s primary link to the global internet went out. Many Somalis were understandably concerned:

However, despite its tremendously unfortunate timing, this Internet outage was due to emergency downtime on the EASSy cable, which was needed to repair a cable break that occurred the previous week near Madagascar... Regardless, 12 presidential candidates walked out on the debate believing the outage was a political dirty trick.

Most recently, YemenNet suffered a multi-hour outage, leading to speculation that the internet blackout was retaliation for missiles fired from Yemen at Israel’s key Red Sea shipping port of Eilat.

The speculation led cable owner GCX to publish a rare statement of explanation the following day:

With reference to the recent internet outage in Yemen reported in some media outlets, GCX can confirm that a scheduled maintenance event took place on 10th November on the FALCON cable system in conjunction with the Yemen cable landing party. This maintenance event had been in planning for the past 3 months and was notified to all relevant parties and was completed successfully within the agreed maintenance window.

The secrecy around submarine cable maintenance events does not serve the public interest. It is long overdue for the submarine cable industry to develop a practice of widely disseminating (beyond just direct customers) advanced notice on any scheduled cable maintenance activity that could lead to a widespread internet blackout.

In a time of heightened tensions around the world, not doing so could have grave consequences.