Data-Driven Defense: Exploring Global Cybersecurity and the Human Factor

Summary

A data-driven approach to cybersecurity provides the situational awareness to see what’s happening with our infrastructure, but this approach also requires people to interact with the data. That’s how we bring meaning to the data and make those decisions that, as yet, computers can’t make for us. In this post, Phil Gervasi unpacks what it means to have a data-driven approach to cybersecurity.

A security breach often manifests itself in some sort of performance degradation of services — a slow network, an application that isn’t behaving correctly, or in some scenarios, a complete hard down. But this isn’t always the case. Especially when an attacker is interested in covert data exfiltration, a breach may go unnoticed for weeks, months, or even years.

So how can we ever know if we’re under attack when a determined adversary can go unnoticed for so long?

The answer isn’t purely technical. There is no silver bullet that can solve all of our security problems and prevent any and all would-be attackers from carrying out an attack. Instead, to be as effective as possible, a cybersecurity defense posture has to be a two-pronged approach.

It must be data-driven and consist of the appropriate volume and types of telemetry necessary for situational awareness from a high level to the most granular. It also needs the human factor, or in other words, the subjective and critical decision-making ability of a human being.

A data-driven approach

A strong security posture means constant vigilance, which means the continuous collection and analysis of telemetry from various sources. This includes infrastructure devices involved with running and delivering services and applications, as well as the code underlying those services.

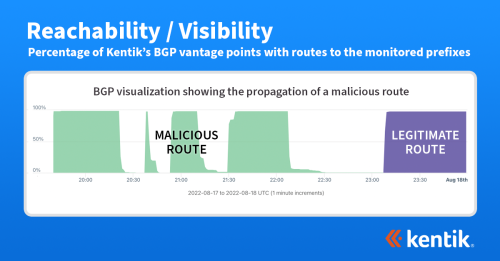

This could encompass packet captures, flow records, server logs, routing advertisements, file access records, etc. In a large organization, this is both a huge volume and a massive variety of data to process, analyze, and store.

For example, a threat feed can tell us what a particular attack looks like. Using appropriate data analysis methods, we can analyze a large volume of telemetry in real-time to find evidence for that attack. We can look at flow records, interface utilization, server logs, and more to see what type of attack we’re experiencing, who it’s affecting, when it started, and so on.

However, this is only part of the process. A data-driven defense also means a subjective component — the human factor.

The human factor

In a recent episode of Telemetry Now, TJ Sayers, Manager of the MS and EI-ISAC’s Cyber Threat Intelligence team at the Center for Internet Security, explains that almost 85% of incoming alerts, alerts for a potential attack, are reviewed by actual human beings to judge if the alert warrants further action. As much as a sophisticated data science workflow can augment the threat hunting and analysis process, the actual human interaction with the data still provides a true understanding of the data.

In this case, it takes a human being to determine if a threshold that was exceeded, or a file that was accessed outside of business hours, is significant and meaningful. TJ explained that a big part of a strong security posture is simply open communication among teams. With good communication, a security analyst looking at some strange behavior just needs to ask the network engineer, application owner, or sysadmin if that event is indeed something to worry about.

Although the industry is working on systems to do this programmatically, adding this subjective component to a machine learning workflow is no small feat. Yes — a statistical analysis algorithm and an ML model can significantly help us, especially with organizing data, identifying patterns, and detecting anomalies. However, those technologies still need to improve in providing the subtle and subjective insight only a human can provide.

For example, consider an alert for link utilization reaching 100% on a pair of active/standby data center WAN ports. This behavior is unexpected and seems to correlate with a known active DDoS attack occurring against similar organizations in the region.

With this information, a system could automatically kick off a mitigation workflow, but a SOC engineer might approach this differently. With a quick call to the data center team, an L1 SOC engineer would learn that the team just kicked off a replication task across the WAN but didn’t notify anyone. Ultimately, this was not a security incident but poorly planned maintenance.

Data and people

People processes, communication, and incident response workflows aren’t necessarily data themselves but are part of a data-driven approach to cybersecurity. Otherwise, the data is simply more noise leading to alert fatigue, security breaches, and attackers having their way with our networks.

We need the data for situational awareness and the assistance of programmatic workflows to help us sort, organize, and analyze that data. However, a data-driven approach to cybersecurity also requires people — human beings — to interact with the data bringing meaning, finding significance, and making those decisions that machines still need to be genuinely able to make.