Summary

This year-end wrap-up covers topics from BGP security (including ASPA and excessive AS-SETs) and the geopolitical (Ukraine’s IPv4 exodus, the Iran internet shutdown, and Red Sea cable cuts) to the year’s most significant outages (TikTok, the Spain/Portugal blackout, and cloud failures at AWS, Azure, and Cloudflare). Plus, we explore Starlink’s new Community Gateways, and revisit the evolving landscape of AS ranking and OTT service tracking.

We’ve made it through another year, and it’s time for our end-of-year wrap-up highlighting the key analyses we published in 2025. If you enjoy reading through these highlight reels of internet measurement, take a look at the previous editions for 2022, 2023, and 2024, as well as our list of the top outages from 2021.

As we did in previous editions, we’ll group the analysis into a few categories. This year’s report will again center on BGP security, geopolitics, and outages, ending with a couple of special topics.

Let’s dig in!

BGP security

This year, we continued our series examining BGP route leaks entitled Beyond Their Intended Scope with a post about a leak from Brazil, as well as one by a DDoS mitigation provider. The leak covered in the first post was a “path leak,” which concluded by making the case for the routing security mechanism Autonomous System Provider Authorization (ASPA) since “origin-based solutions like RPKI ROV would not be in a position to help.”

The second piece set up the topic of problematic AS-SETs. The leaker in this case has an AS-SET that expands to over a million entries, largely defeating the purpose of the mechanism and incurring computational waste along the way. This was a topic I returned to in a later post, The Scourge of Excessive AS-SETs.

I presented on the AS-SET issue at NANOG 94 in Denver, APRICOT in Kuala Lumpur, and AUSNOG in Melbourne. Our friends at Cloudflare continued the analysis of excessive AS-SETs with their own blog post and in their talk at NANOG 95 covering route leaks.

Additionally, we covered a couple of mishaps involving RPKI this year. North Korea became the first on the Korean peninsula to create ROAs for all of their address space — still just four /24’s. But unfortunately, due to a fairly common ROA misconfiguration, they rendered their routes invalid, knocking their tiny internet offline. The hermit kingdom’s self-inflicted outage confirmed that invalid routes get filtered — and that forgetting to check your ROA prefix lengths is a great way to unplug yourself from the internet.

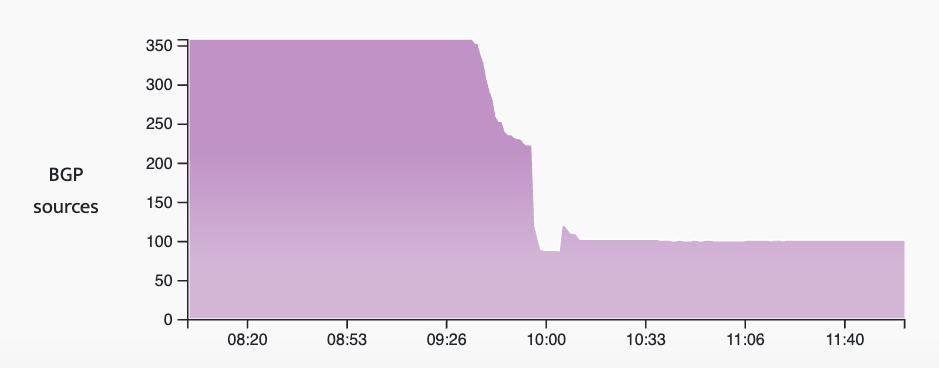

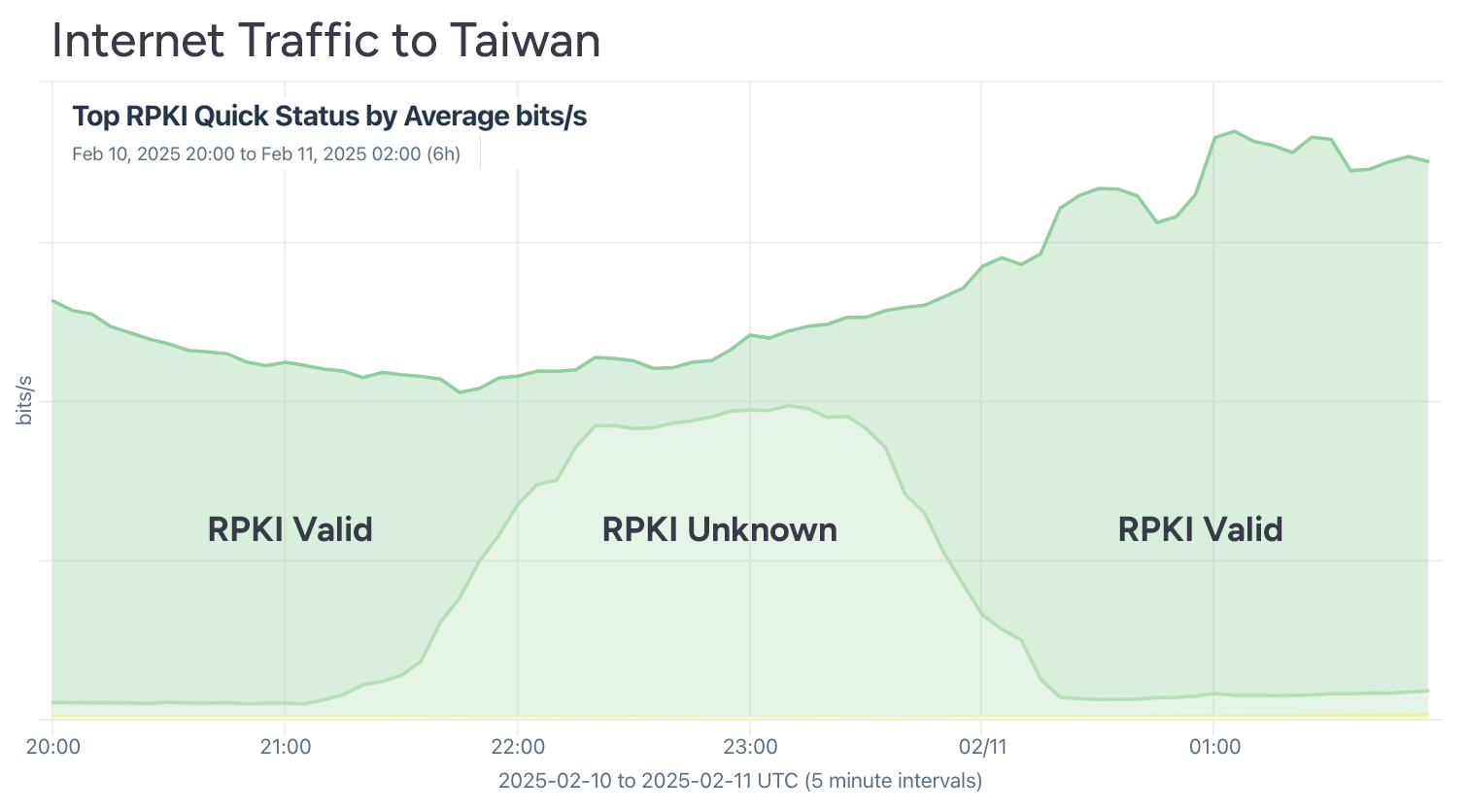

In February, Taiwan experienced an RPKI breakdown when all of the objects that Taiwan NIC publishes accidentally expired. On the bright side, no traffic was disrupted during the outage (visualization below), showcasing RPKI’s fail-open philosophy. Of course, during this brief incident, Taiwanese routes would not have been able to employ ROV to fend off hijacks.

For an overview of our stats and perspective on the state of routing security and RPKI ROV adoption, be sure to check out this LinkedIn Live Event hosted by IPXO, my podcast with APNIC, as well as this routing security webinar from April.

Geopolitics

In my piece Exodus of IPv4 from War-torn Ukraine, I analyzed how much IPv4 space had migrated out of Ukraine since the Russian invasion of February 2022. In the process of reporting this development, I was able to reach some Ukrainian providers, including incumbent Ukrtelecom, who confirmed to me that they were leasing out their IPv4 space as part of an effort to secure desperately needed financial support to fund their operations.

The analysis received some media attention and spurred legendary security journalist Brian Krebs to dig deeper into the proxy services using these leased Ukrainian address ranges. More to come on this topic in the coming year…

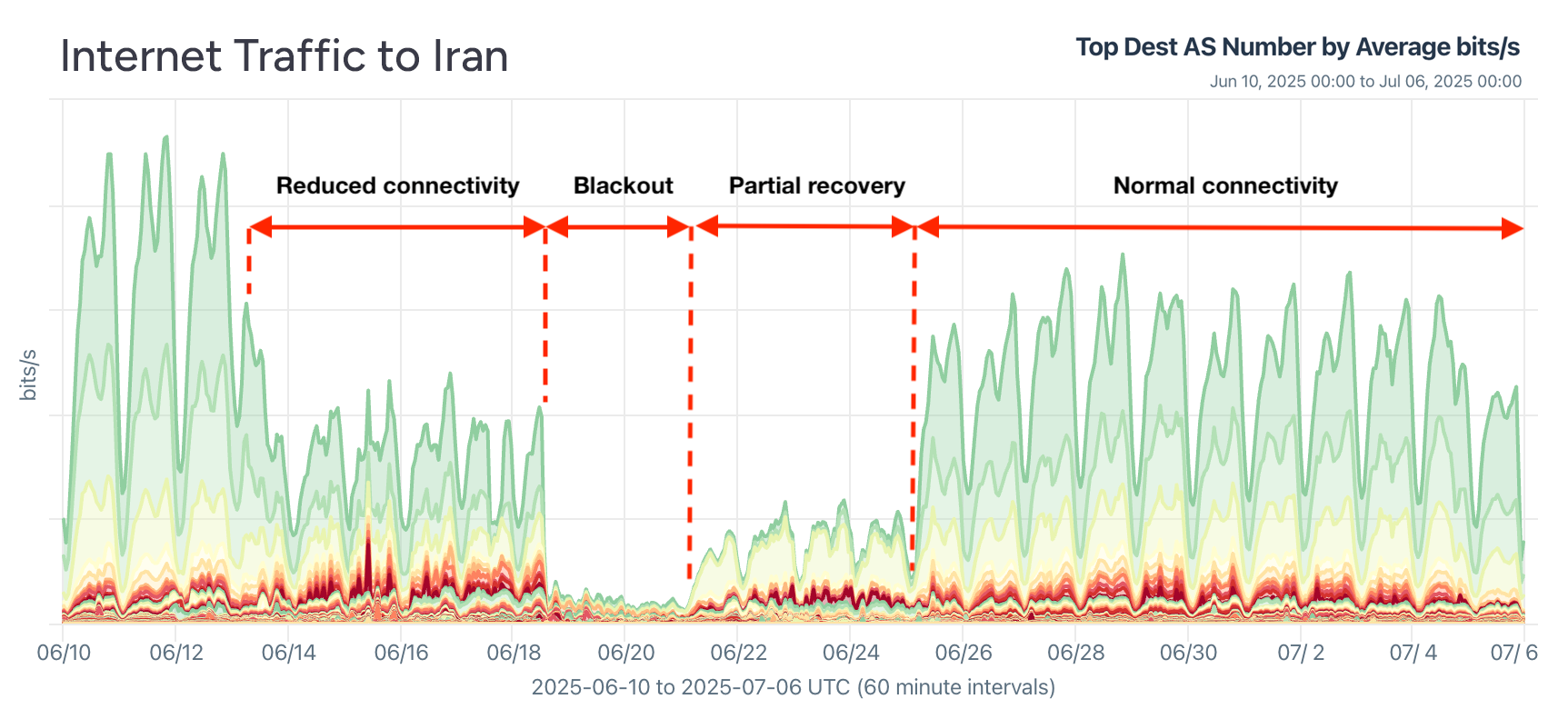

During the Twelve-Day War between Israel and Iran this June, Iran shut down parts or all of its internet, purportedly to defend themselves from cyber attacks and drone strikes. We, along with other internet watchers, reported on the various stages of the shutdowns in Iran and contributed to a lengthy report on the incident by the Miaan Group, an organization that works to support internet freedom and the free flow of information in Iran and the wider Middle East.

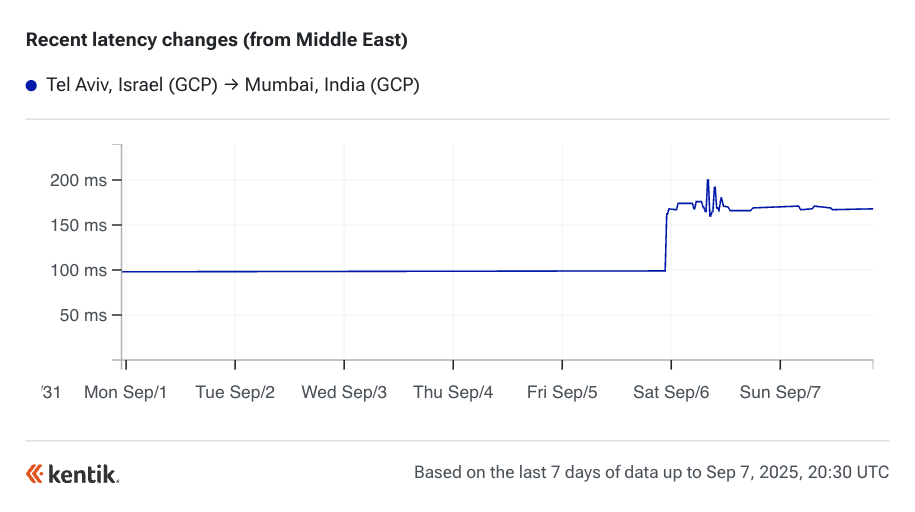

In Subsea Cables Parted in Red Sea Again, I analyzed the impacts of the latest submarine cable cuts in this problematic body of water. Focusing on internet disruptions between Europe and Asia, I employed Kentik’s public Cloud Latency Map (CLM) to document the impacts observed between the regions of AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud, as shown below. (More CLM analysis can be found here).

This round of submarine cable cuts got a lot of attention in the Middle East. I was interviewed by the Associated Press, Fast Company, The Independent, and for a podcast from Dubai-based outlet The Agenda.

This year, Afghanistan imposed its first nationwide internet shutdown, cutting off connectivity to “prevent immorality” — a blow to digital freedoms, education, and media already under severe strain since the Taliban’s 2021 return. It was my second time covering the internet situation in Afghanistan since my 2021 post immediately following the departure of the US military. As I discussed with German broadcaster Deutsche Welle, the shutdown realized many fears following the Taliban’s return to power.

Other geopolitical-related outages in 2025 included a shutdown in Tanzania, pulsing disruption in Cameroon, and some unusual blocking activity from China’s Great Firewall.

Outages

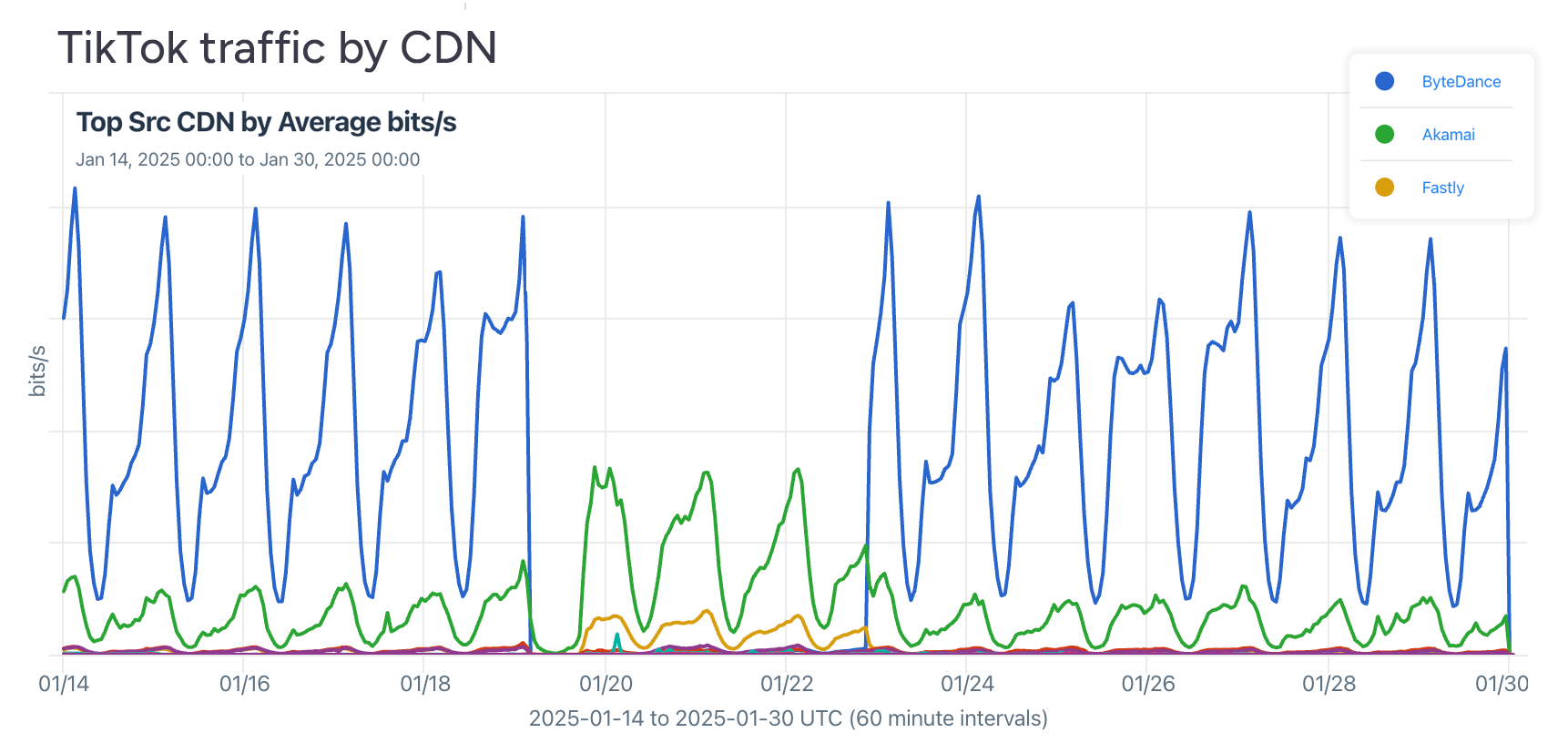

This year began with a 14-hour outage of the popular short-form video service TikTok. I wrote a post on the outage of TikTok and, using Kentik OTT service tracking, I was able to show how its restoration briefly came without the support of parent company ByteDance’s US CDN. Today TikTok remains operational despite a ban written into law passed by Congress, signed by a president, and unanimously upheld by the Supreme Court.

On April 28, Spain and Portugal experienced the largest electrical blackouts in their histories, knocking out power across the Iberian Peninsula and causing widespread disruption to daily life and critical services. Our analysis showed that the corresponding internet outage began around 10:34 UTC, with traffic in Spain and Portugal dropping dramatically as electricity failed, underscoring how fundamentally the internet depends on reliable power.

The outage’s effects rippled beyond the Iberian Peninsula, impacting international connectivity in countries like Morocco and even as far as Angola, due to dependencies on Spanish and Portuguese transit links. We also highlighted how satellite internet provider Starlink was affected in Spain as users were rerouted to ground stations outside the country to maintain connectivity.

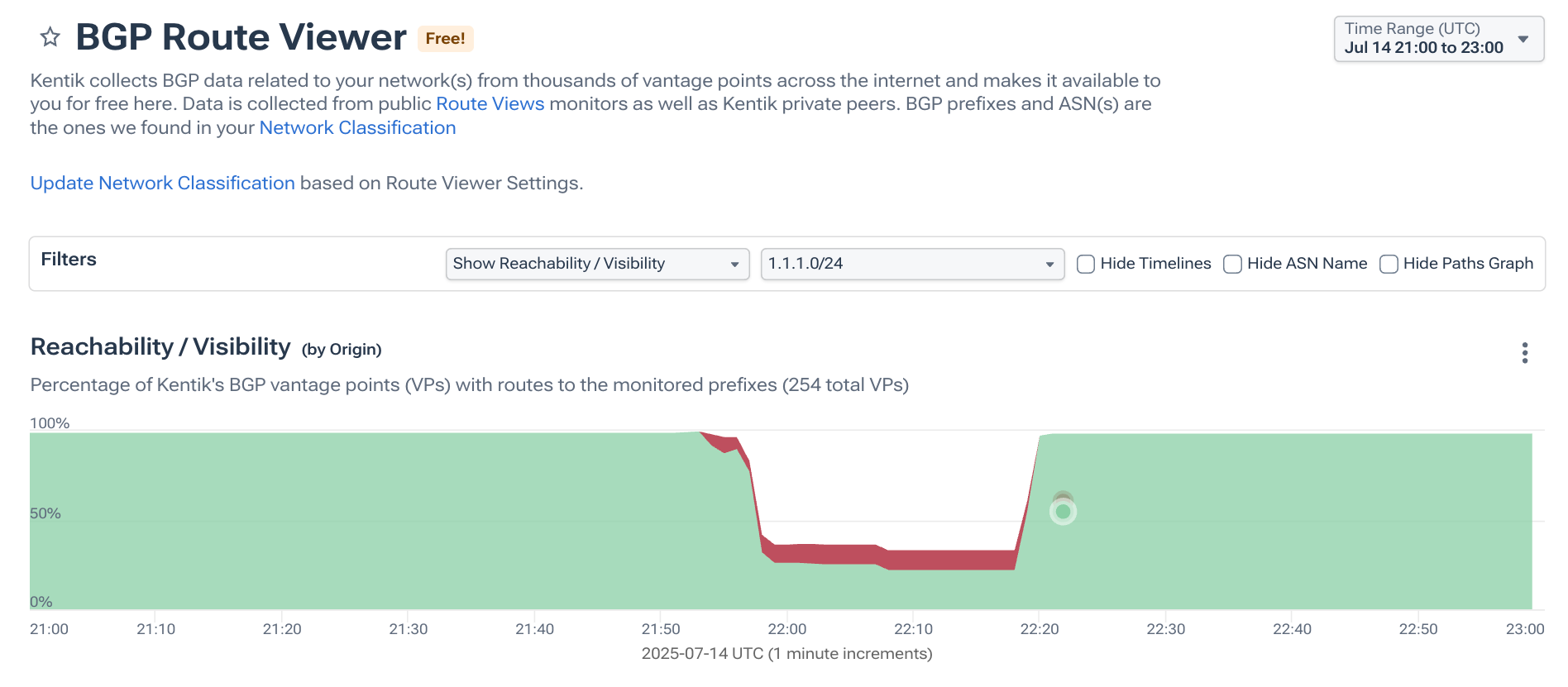

In July, Cloudflare’s popular public DNS resolver, 1.1.1.1, suffered a major global outage, and almost immediately, the internet rumor mill pointed to a BGP hijack as the culprit. In my post on the incident, I explained that the theory never held up. Instead of an attack, the outage stemmed from Cloudflare itself withdrawing its DNS prefixes, which effectively made the service unreachable for many networks.

In the post, I expanded on why 1.1.1.0/24 is such an unusual block. Thanks to years of widespread internal use, it’s especially prone to strange routing behavior whenever legitimate announcements disappear. In this incident, RPKI ROV helped limit the spread of a bogus route from India, but couldn’t prevent the outage created by the withdrawals themselves.

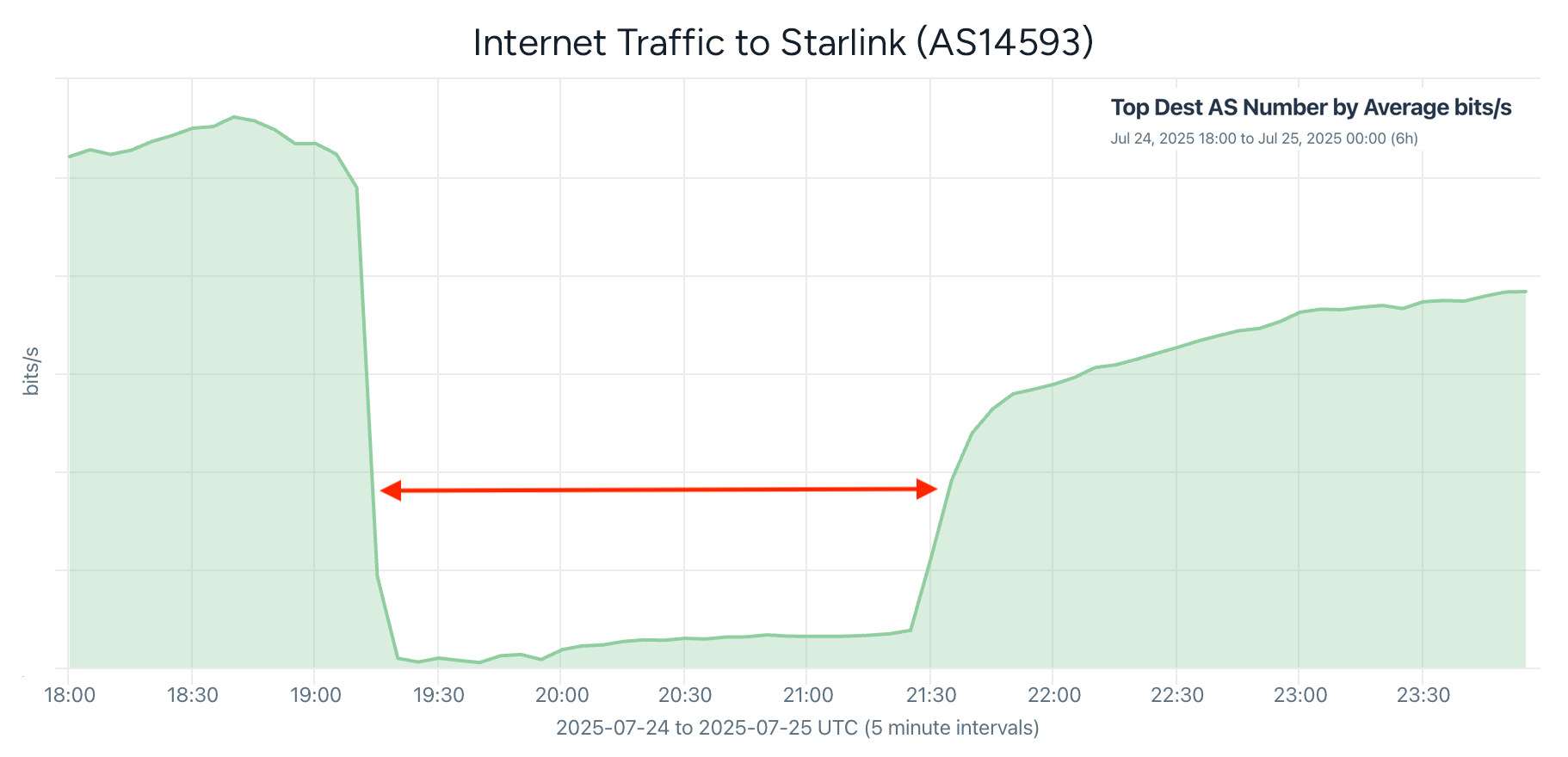

Later in July, Starlink suffered its largest outage in years — a worldwide disruption that lasted more than two hours and took millions of users offline. Our analysis looked at the outage and how Starlink’s expanding Community Gateway service, which provides internet transit to remote locations, was affected when the core network went dark.

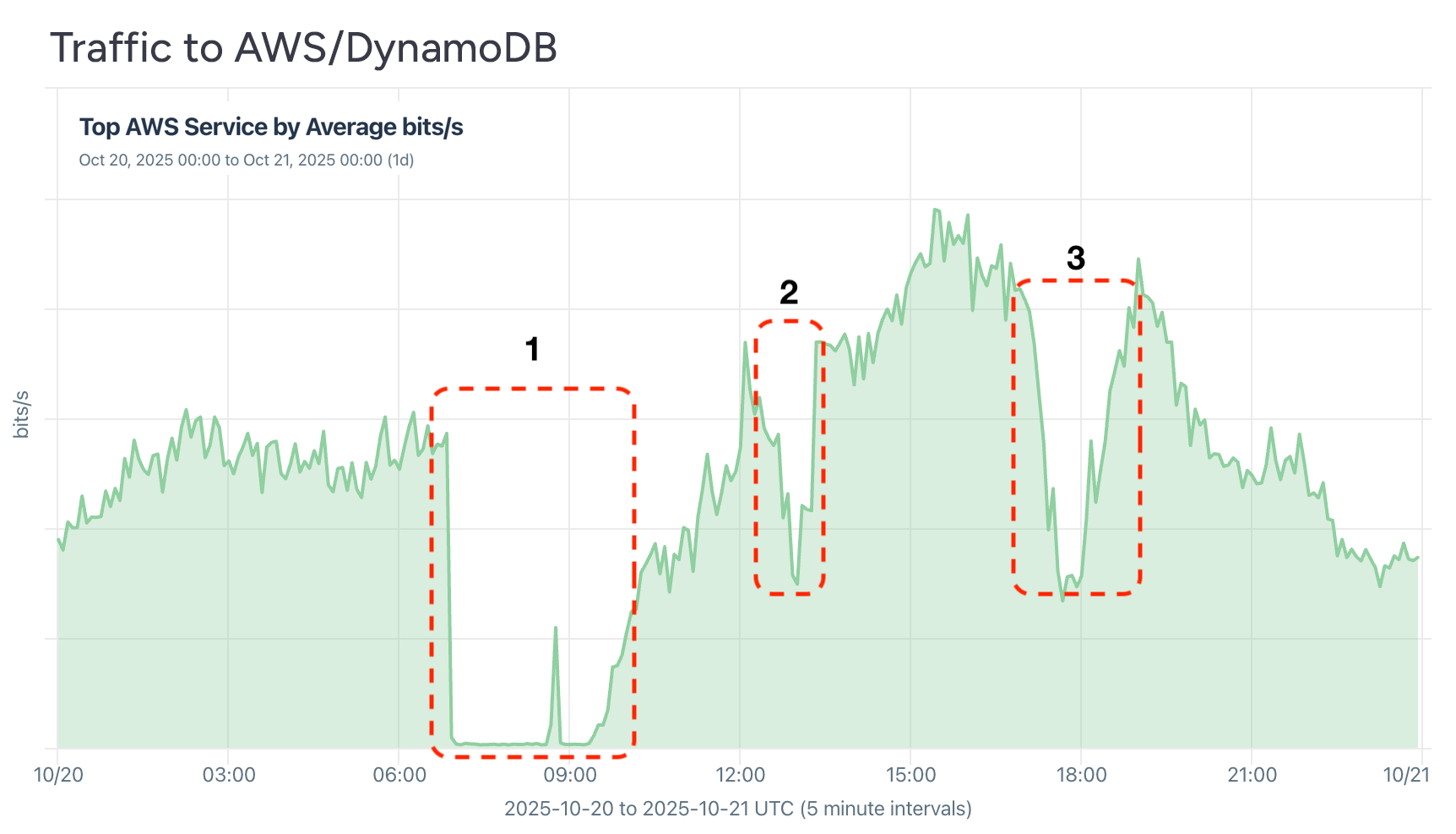

This year’s most talked-about outages were definitely the major cloud disruptions that struck the internet in the final quarter of the year. This first, and perhaps most disruptive, was the big AWS failure on October 21st. It was the latest big outage to be caused by a bug in automation software.

According to the post-mortem, the culprit was the software managing Domain Name System (DNS) for AWS’s DynamoDB managed database service. During the incident, AWS systems and customer apps couldn’t correctly translate hostnames into network addresses, so they couldn’t connect to DynamoDB. Below is the drops in the traffic from Kentik customers to DynamoDB as the service suffered multiple outage throughout the day.

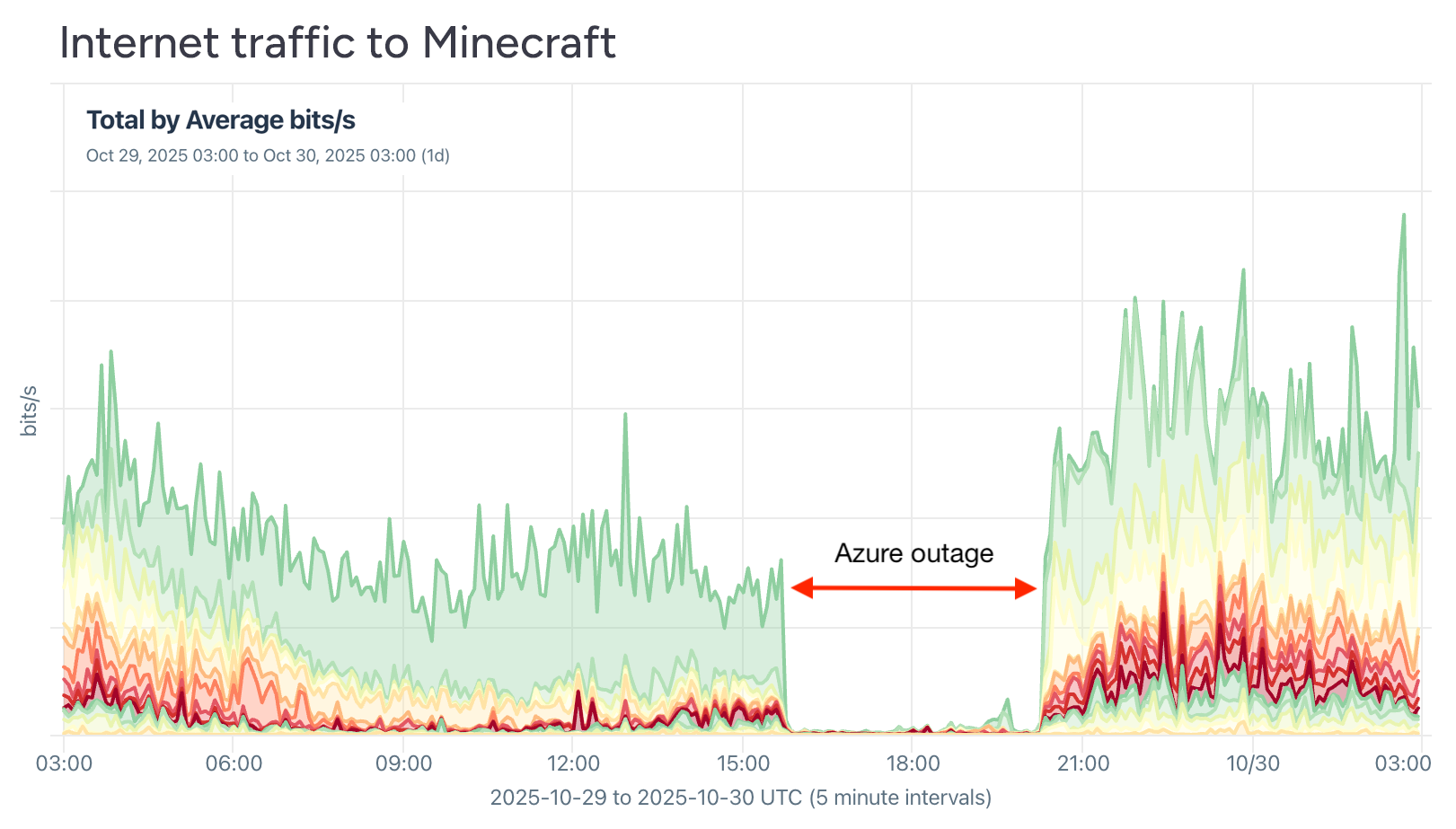

Within days the massive AWS outage, Microsoft had its own cloud-wide outage. According to the incident retrospective, a customer made a valid configuration change across two different Azure Front Door (AFD) control-plane build versions, which generated incompatible configuration metadata. When this metadata propagated globally, it triggered a latent bug in the AFD data plane, causing widespread crashes and disrupting internal DNS resolution at edge sites.

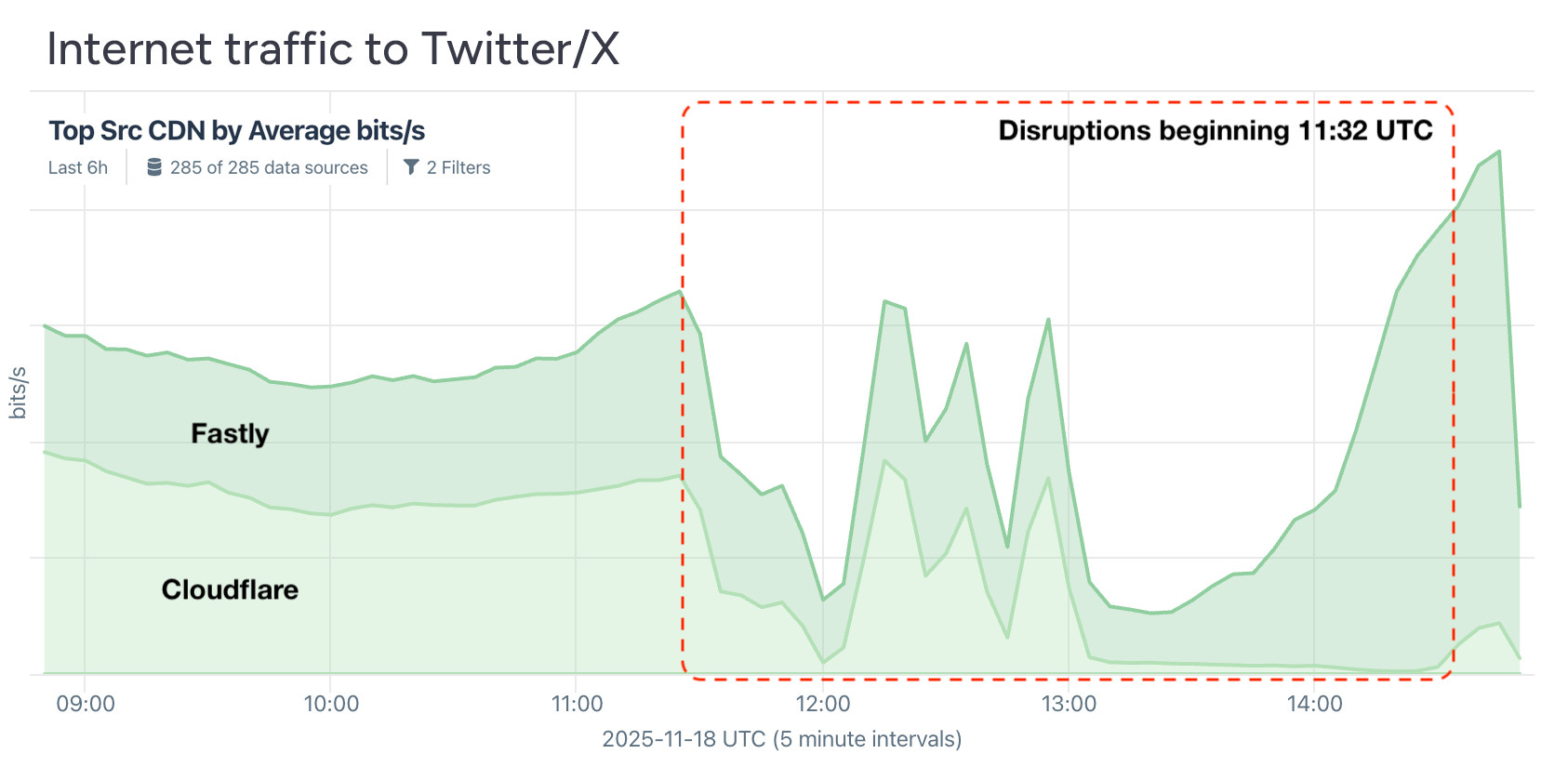

Then Cloudflare had its own big outage on November 18th when a seemingly small permissions change in one of their database systems caused the generation of a feature-file used by their Bot Management system that was twice its normal size. When that oversized file propagated across their global network, it exceeded limits within a core proxy module and triggered a widespread failure. At first glance, the symptoms resembled a large-scale DDoS attack, which added to the initial confusion.

To put it all into context, I spoke with Zoe Turner of Data Center Dynamics in a festive end-of-year chat. Much has been made about the consolidation in the hosting space: just a handful of companies provide the services that power nearly every aspect of our digital lives. When one goes down, it can feel like the whole internet is broken.

However, I’d like to remind everyone of what things didn’t break. In each of these big incidents, no fiber optic cables or other physical media were broken, and the global (as opposed to internal) DNS and BGP systems continued operating just fine. In other words, the fundamental layers of the internet, famously designed to survive a nuclear blast, never experienced an outage.

Each major cloud provider experienced its own outage at different times. During the AWS, Azure, and Cloudflare incidents, the other clouds (along with Google, Facebook, and their various services like WhatsApp, YouTube, and Instagram) remained online, giving people plenty of places to complain about what wasn’t working.

For years, automation bugs — not cyberattacks — have been the leading cause of large-scale outages. Operating at this scale requires automation, but the constant push for new features increases complexity and, with it, the risk of catastrophic failure.

Services that can’t afford a multi-hour outage every year or two will need to diversify their hosting. Everyone else will simply have to endure the downtime — but thanks to consolidation, at least you’ll have plenty of company.

Additional incidents we weighed in on this year included the Vodafone UK outage, the electrical blackout in Chile, Hurricane Melissa in Cuba, and a disruption caused by an earthquake in Kamchatka, one of the easternmost regions of Russia.

Starlink

This year, I spent some time investigating the low-earth orbit (LEO) satellite internet service provider Starlink. The service is an object of fascination to a lot of people, and I am no exception. It is the most innovative development in internet delivery in decades.

In March, I wrote about Starlink’s expansion of services into the transit market using something they are calling Community Gateways. These configurations reuse idle Ka-band bandwidth, typically reserved for high-capacity downlinks to ground stations, and apply it to high-capacity uplinks for service providers in remote regions.

Starlink makes use of its unique optical inter-satellite links (OISLs) to route traffic across its satellite constellation to another downlink, enabling the service to become a transit provider to bandwidth-starved locales like remote islands and frigid parts of the Arctic.

This year, I published latencies we measured to the tiny island nation of Nauru in the South Pacific, showing the discontinuities as the antennae jump from satellite to satellite. In addition, I posted the first evidence of the activations of Community Gateways in the Galapagos Islands and Nome, Alaska.

Another angle I took on Starlink was to analyze the geolocation file they publish. As I described in a two-part feature for the Internet Society’s Pulse blog (Part 1, Part 2),

Soon after the arrival of Starlink service in Ukraine, I began downloading Starlink’s IP geolocation file every two hours. This month, I passed three and a half years of snapshots of these files — likely the largest collection of Starlink IP geolocation data outside of Starlink itself.

The most interesting material may be in Part 2, which highlights some intriguing changes we observed, concluding with an interactive visualization that we’ve continued to update since publication. Buried in the visualization is a table that compares the date of the first appearance of a geolocation entry and when the service was officially announced, showing the correlation between updates in the geolocation file and real-world events. My posts announcing Starlink’s first geolocation entries for Vietnam and India come from this dataset.

AS ranking

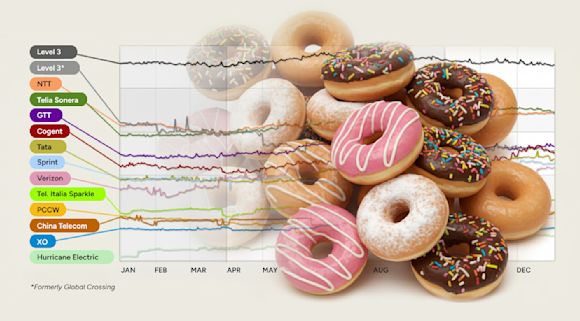

Back by popular demand, I revisited the old Baker’s Dozen blog series that my former colleagues at Renesys used to publish. Those analyses would rank the top transit ASes of the internet, but this time I extended it to illustrate, using an interactive visualization, how those top ASes changed over 20 years.

It discusses how the role of traditional transit has evolved as content delivery and peering relationships now carry the bulk of traffic, and how de-peering and the default-free zone (DFZ) can lead to internet partitions.

Finally, the post puts transit into context by delving into a sample breakdown of traffic volume for a typical mid-sized US service provider by connectivity type: transit vs peering vs embedded cache vs IXP. Bottomline: regardless of how it’s sourced, it’s practically all content, which is why Kentik built its OTT Service Tracking capability.

OTT Service Tracking

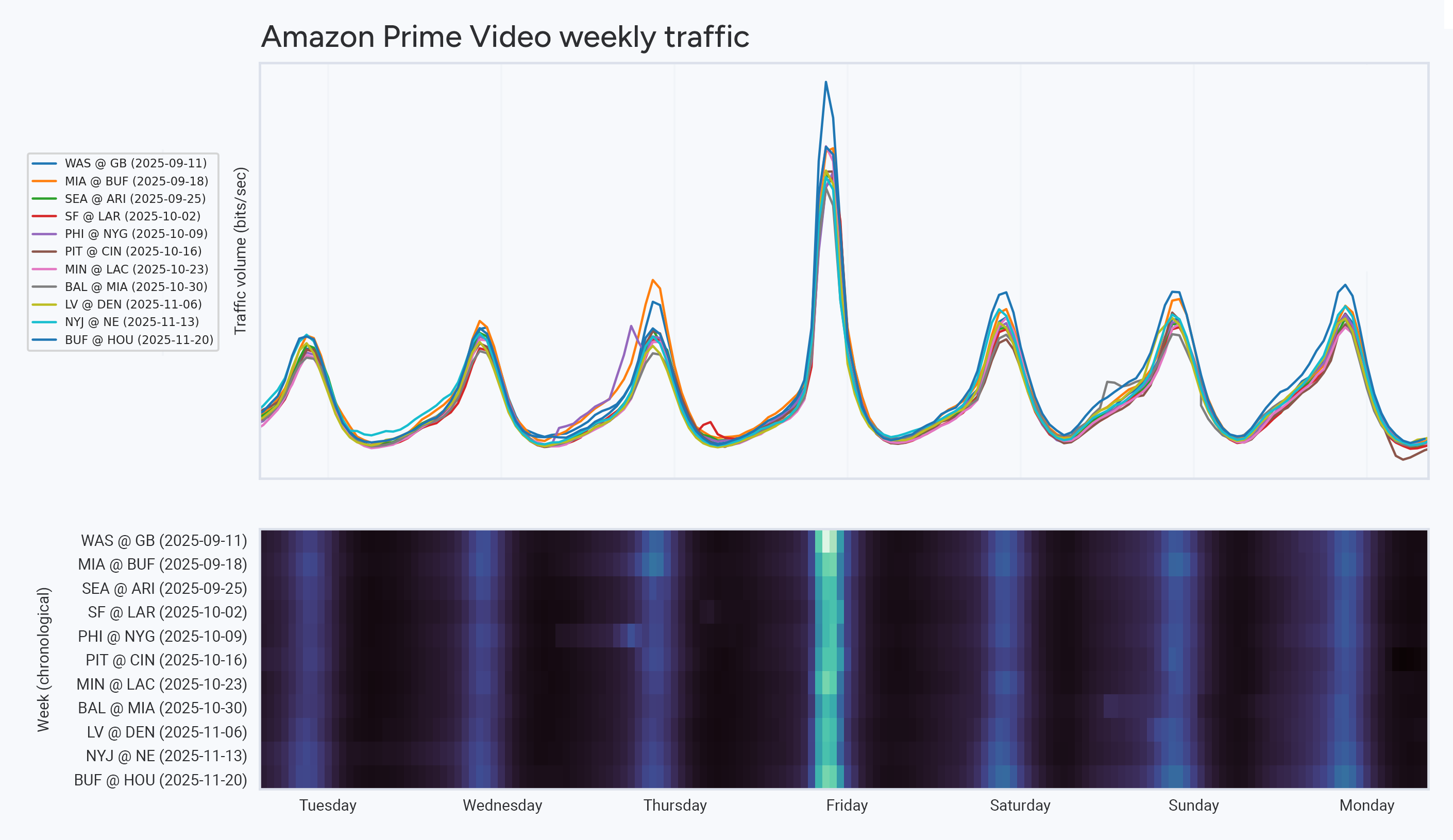

In our continuing Anatomy of an OTT Traffic Surge series, I covered Netflix’s new streaming deal with professional wrestling as well as another look at Thursday Night Football (TNF) on Amazon’s Prime Video.

In the latter analysis, I showed how TNF is the most popular thing on the streaming service (when measured by bits/sec). The visualization below is a game-by-game weekly breakdown showing the peaks of traffic on Thursday night for Prime Video.

Onward to the new year!

It was another eventful year, and we tried to cover it all. If this is a area that interests you, check out my interview entitled Seeing the Internet With Doug Madory on the Total Network Operations podcast published in the spring.

And finally, special thanks to the RouteViews project at the University of Oregon and RPKIViews.org by Job Snijders. Their data and services make BGP research accessible to me and many others. Thank you!