From Ukraine to the Cloud: Stories of IPv4 Migration

Summary

This post expands on our analysis from last year that revealed that as much as 20% of IPv4 space has migrated out of Ukraine in the years following the Russian invasion in February 2022. This update reveals that AT&T (a popular destination for Ukrainian IPs) has since implemented a policy ridding itself of customers using AS7018 to originate their routes, often to support residential proxies.

In May, I published an analysis detailing the 20% decline in the amount of IPv4 space announced by Ukrainian providers since the Russian invasion in February 2022. Much of this decline can be attributed to IPv4 space that is now being leased out as part of an urgent effort to cover the costs of maintaining internet connectivity under wartime conditions.

After I published my analysis, security journalist Brian Krebs produced a detailed follow-up examining how some of that exported address space was being monetized. As Krebs reported, a substantial share of the Ukrainian IPv4 blocks that moved abroad ended up powering commercial “residential proxy” networks — services that enable its users to tunnel traffic through nodes that appear to be ordinary consumer mobile and broadband connections.

Residential proxies are problematic because they are often used to launder illicit activity through legitimate household IP addresses. By leveraging residential IP space instead of data center ranges, these services evade traditional geolocation, fraud-prevention, and IP-reputation systems that might otherwise flag suspicious behavior.

Krebs’s piece also zeroed in on a detail I had observed — that the iconic American telecom AT&T (AS7018) was a popular destination for leased Ukrainian IPv4 ranges that were later used for residential proxies. When contacted by Krebs, a representative from AT&T explained that the company was already at work addressing this issue.

Specifically, AT&T put in place a new policy that required its customers to use their own ASNs to originate customer-provided IP space instead of AT&T’s AS7018. For residential proxy operators, this was a big problem. The IP space they were passing off as part of AT&T’s mobile or broadband networks had to appear to be routed identically to the legitimate IP space. Forcing customers to use their own ASNs made the IP space look different, enabling other networks to identify and, if they choose to, filter traffic associated with those services.

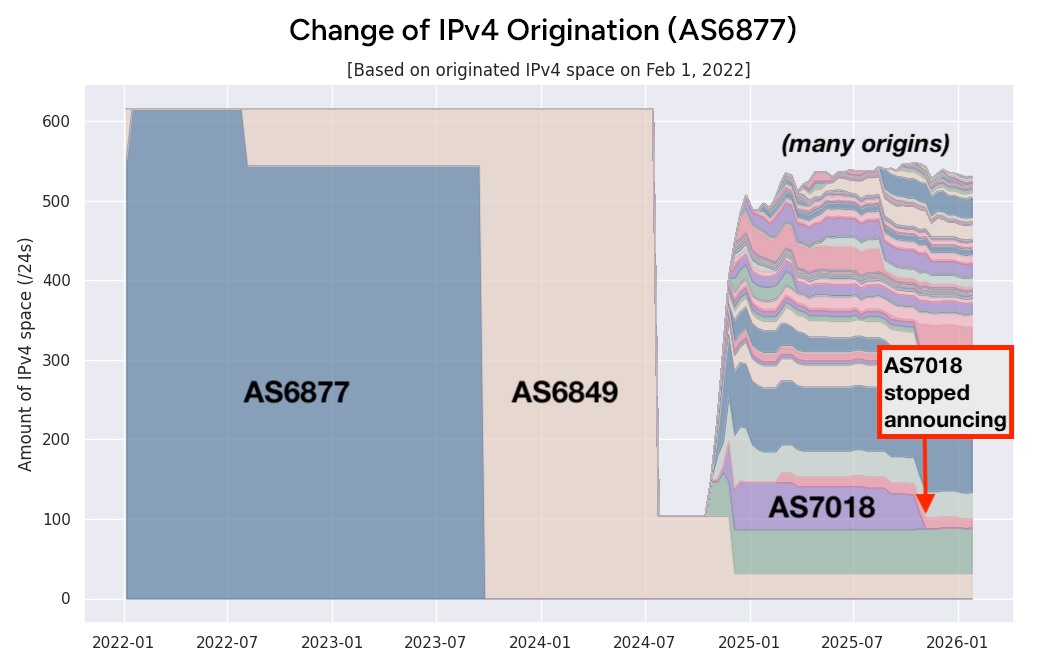

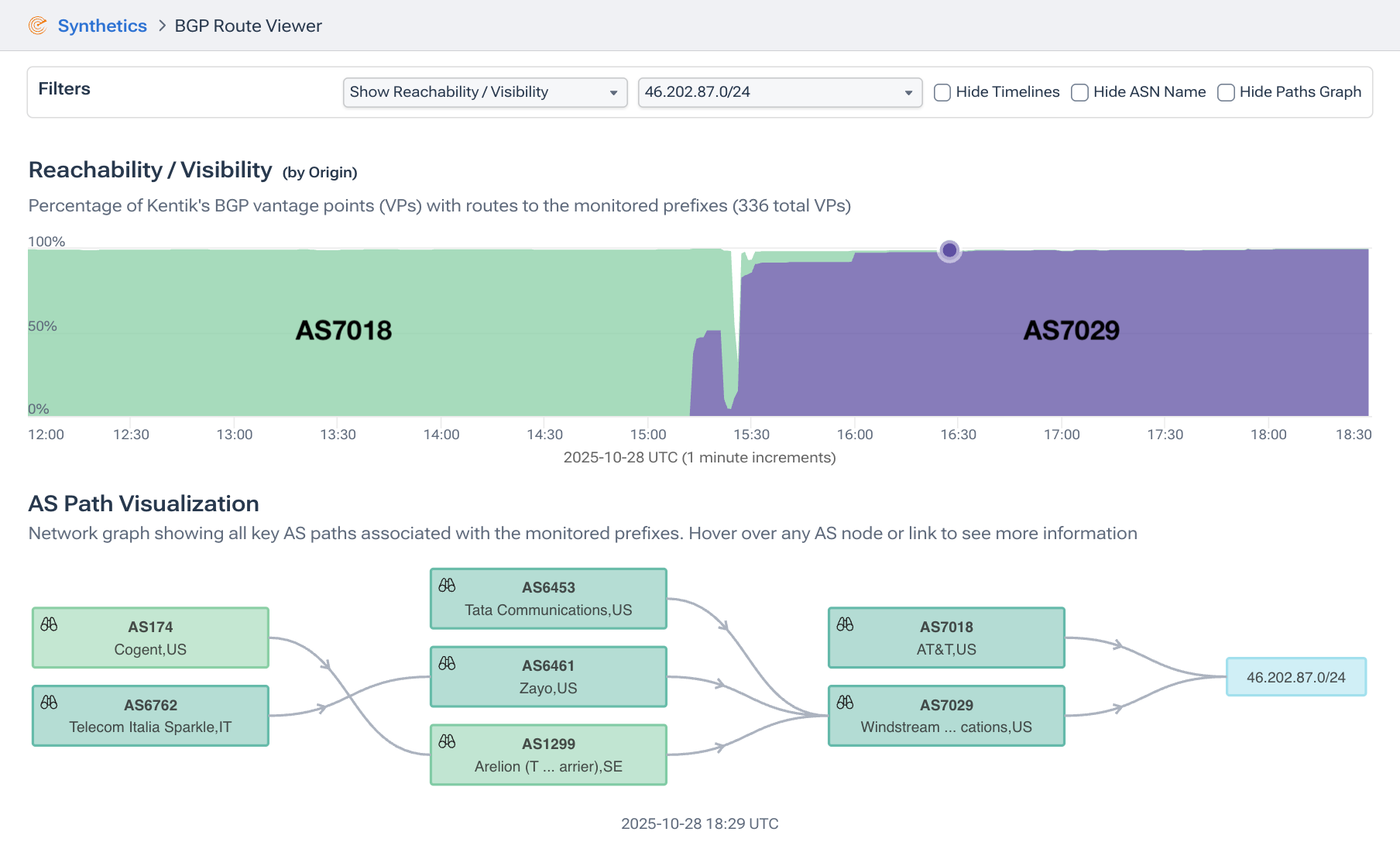

When I recently reran my analysis of the IPv4 space originated by Ukrtelecom’s AS6877 over the past few years, we can see that AS7018 stopped announcing this IP space in late October of this year.

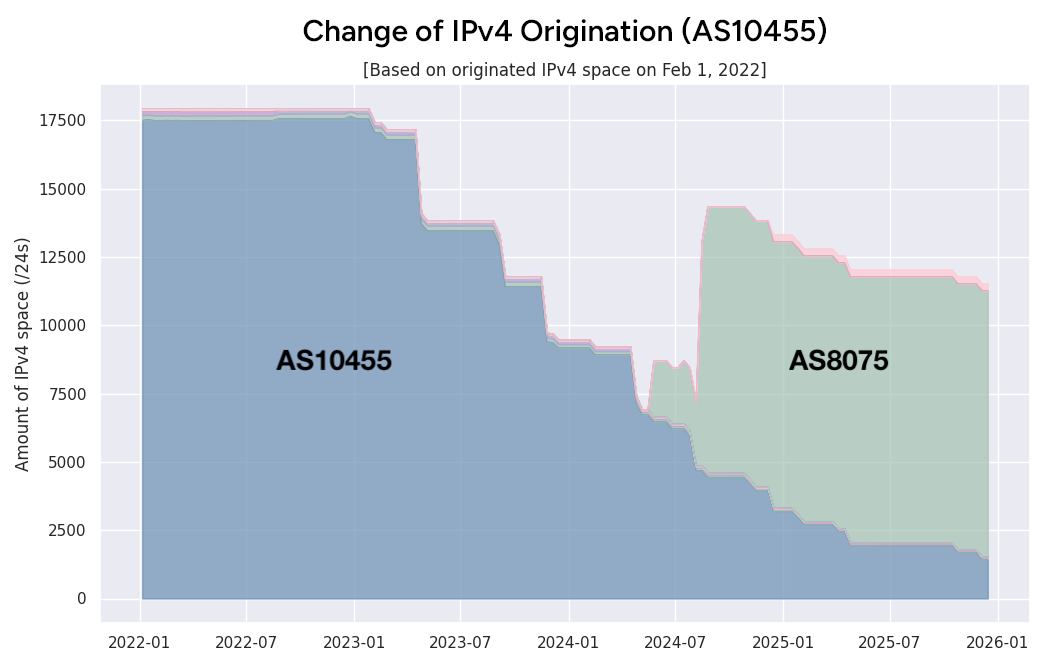

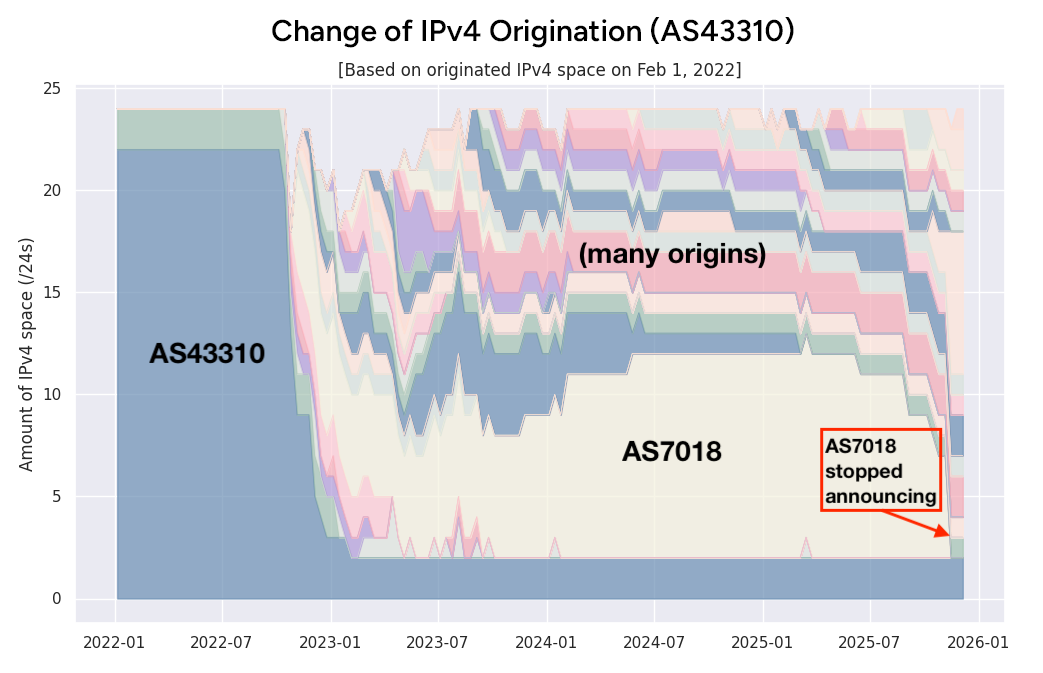

AS43310 was another Ukrainian network that was highlighted in my May post. That network exhibited a dramatic decline in the IPv4 space it originated in, beginning in November 2022. The majority of the address space migrated to dozens of new ASNs around the internet, but none more than AS7018 (AT&T). That stopped as well in October when the IPv4 space originally originated by AS43310 moved off of AS7018’s network and, as happened with AS6877, moved on to Windstream (AS7029).

In each of these cases, the Ukrainian IPv4 space that was previously announced by AS7018 seamlessly moved over to AS7029, as illustrated below. The Kentik BGP visualization below shows the origination change for 46.202.87.0/24 on October 28.

A broader housekeeping effort at AS7018

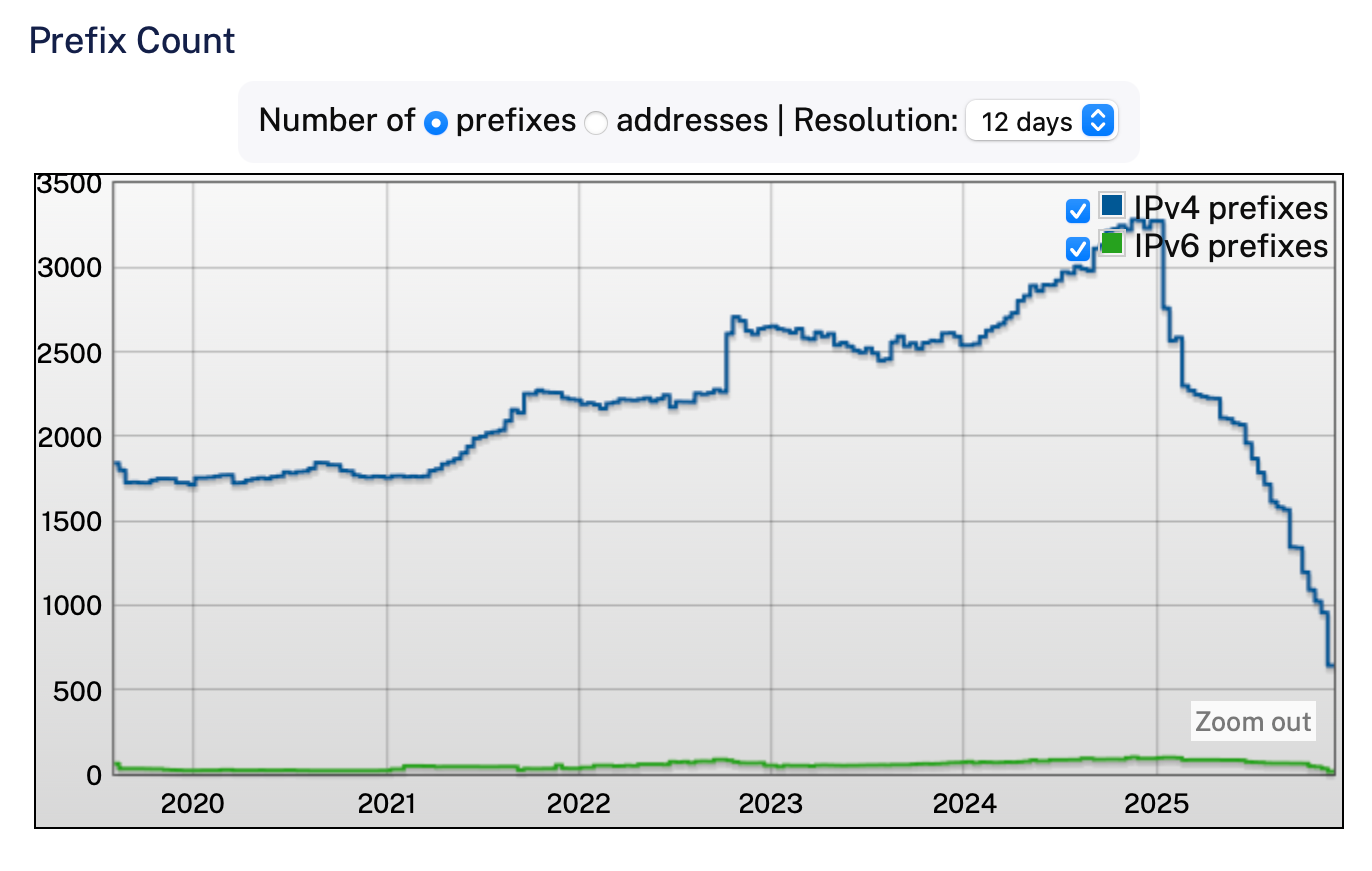

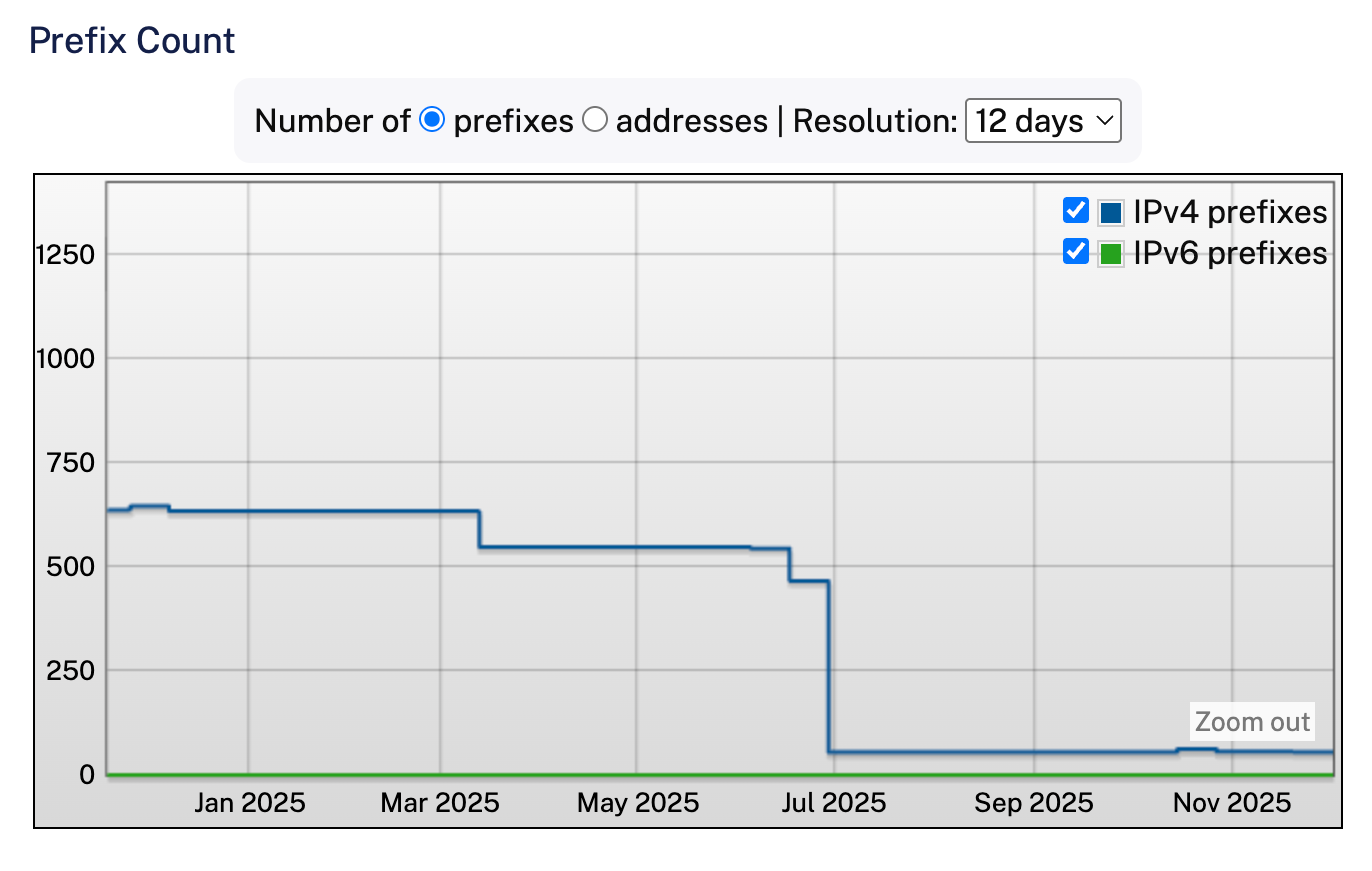

The loss of Ukrainian IPv4 space wasn’t the only factor contributing to AT&T’s recently reduced BGP footprint. Over the course of 2025, AT&T dramatically reduced the number of prefixes they originate—both IPv4 and IPv6—as part of a consolidation of routes. The RIPEstat visualization shown below illustrates the changes over the past year.

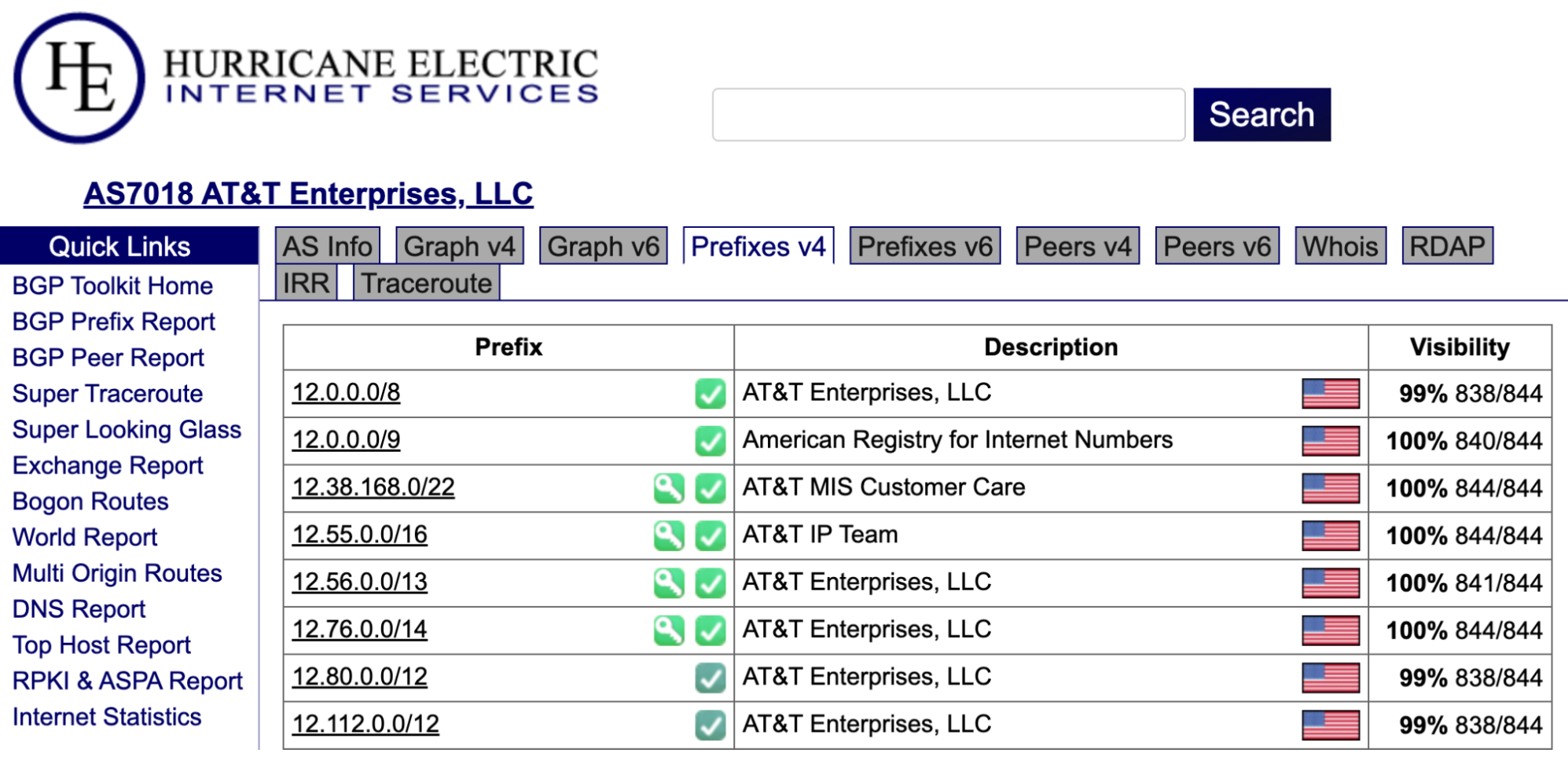

At the start of 2025, AS7018 originated over 3,200 IPv4 routes; today, that number has fallen to 641. Its IPv6 routes have seen a similar drop over the same timeframe, from 92 to just 15. For the first time in years, nearly all the prefixes listed on bgp.he.net as originated by the historical U.S. incumbent are denoted with U.S. flags, as shown below.

So, where did all of those routes go? The top destination, with 588 prefixes, was another AT&T network, AS6389, which underwent its own routing consolidation in 2025, pictured below. Hundreds of /24’s were consolidated into a smaller set of far larger prefixes such as 70.158.0.0/15, 65.81.0.0/16, and 216.76.0.0/14. Another 442 of the prefixes announced by AS7018 at the beginning of the year are simply not currently routed at the present time.

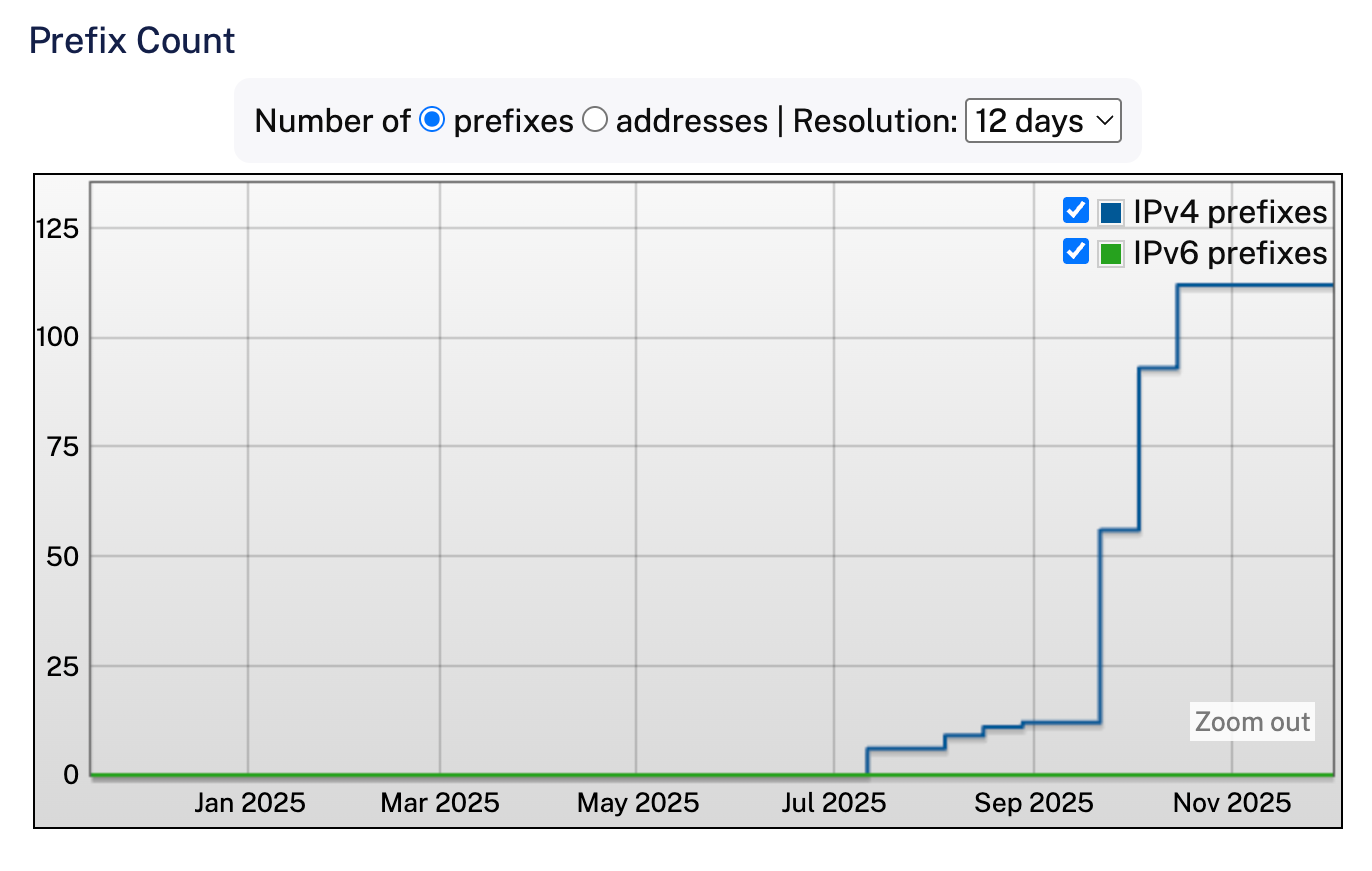

The remaining 1610 are spread across 150 new origins, but a couple of destinations stand out. As mentioned earlier, Windstream (AS7029) became the new home for 357 of the prefixes that left AS7018. Pictured below, Uni Broadband LLC (AS401838) appeared in the routing table for the first time this summer and is currently announcing 112 prefixes, all of which moved from AT&T ASNs.

AS20001, AS20115, and AS55201 all experienced increases in the number of prefixes that originate as a result of the stricter policies at AT&T. The vast majority of the IPv6 routes that disappeared contain address space that isn’t presently routed. Ten IPv6 routes moved to AS7029, such as 2607:6240::/32 and 2607:340::/28.

Other IPv4 migrations

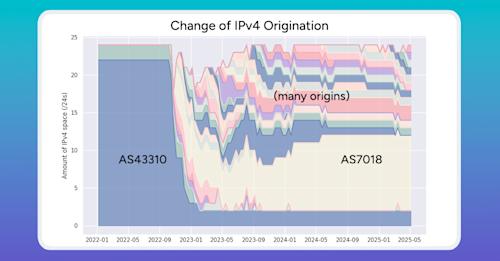

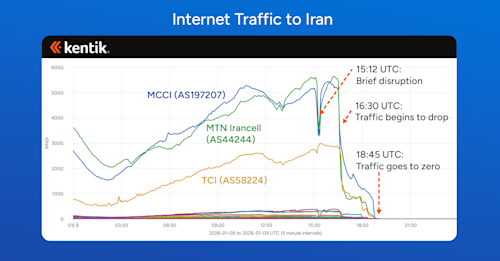

When rerunning this analysis in the past month, I expanded my scope to include all ASNs, not just those from Ukraine. I wanted to understand what other countries may have potentially experienced an outward migration of address space. Only one other country had large networks that exported significant parts of the IPv4 space to the outside world: Iran.

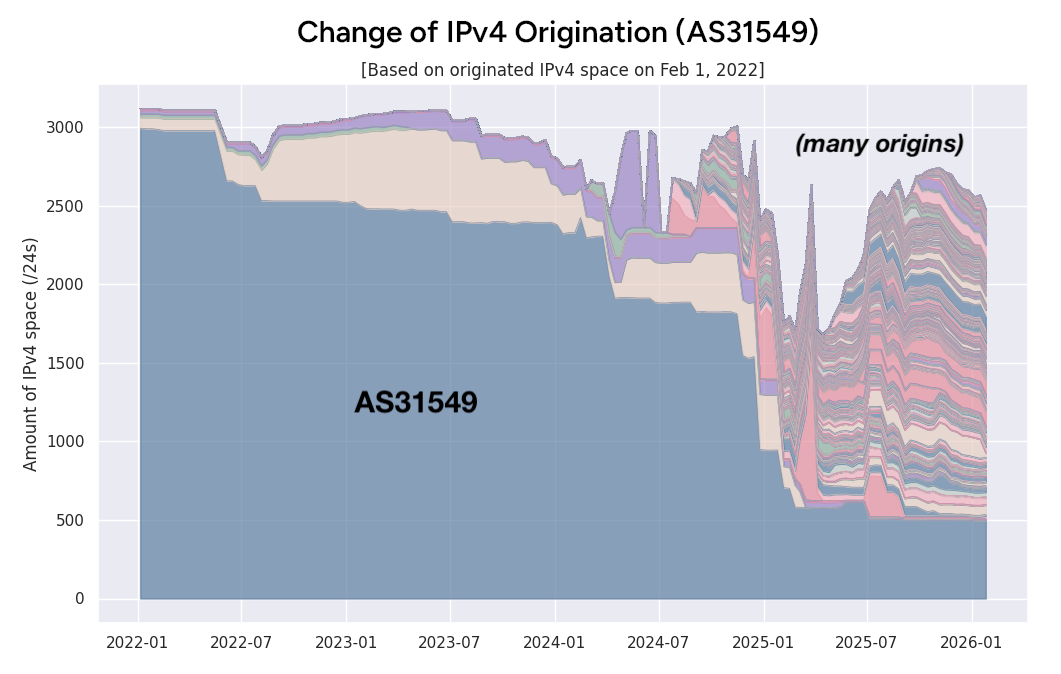

Iranian service provider Aria Shatel (AS31549) dropped by over 2,000 /24’s since 2022. Now, hundreds of ASNs around the world originate from this former Iranian IP space, as is pictured below. Gold IP LLC appears to have handled many of the transfers.

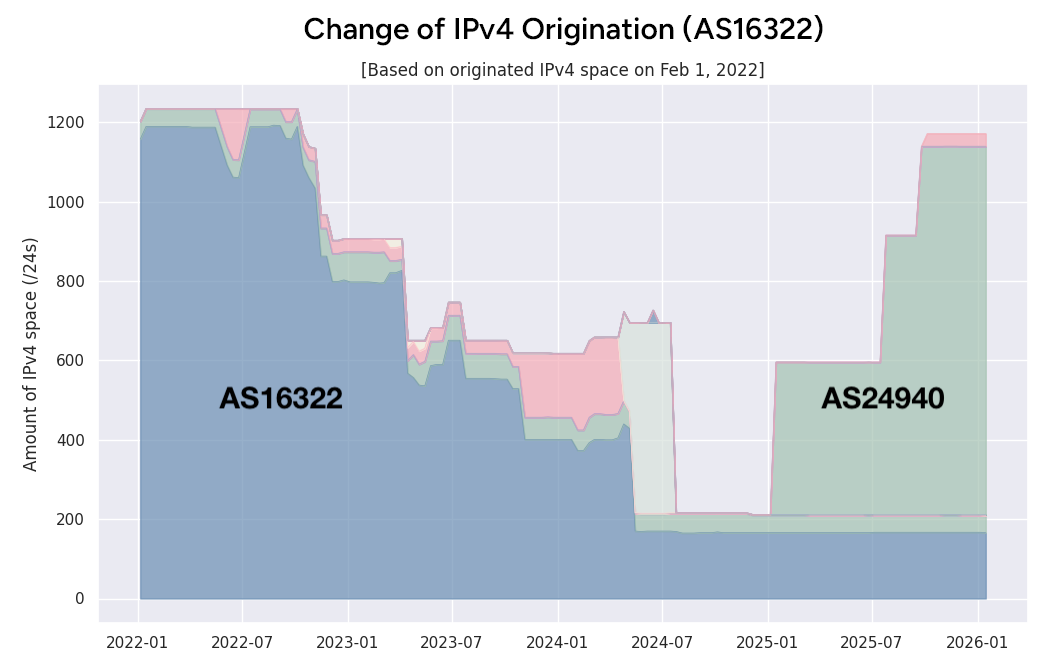

Iranian telecom Pars Online (AS16322) experienced a decline equivalent to over 1,000 /24’s since 2022. Nowadays, most of the lost IPv4 space originates from the German web hosting and data center company Hetzner Online (AS24940). Hetzner Online was also the top destination for the address space previously originated by Iranian service provider HiWEB (AS56402).

IPv4 migration to the cloud

The other major source of large IPv4 movements I identified was not countries at war or under sanctions, but large cloud providers aggressively acquiring available address space.

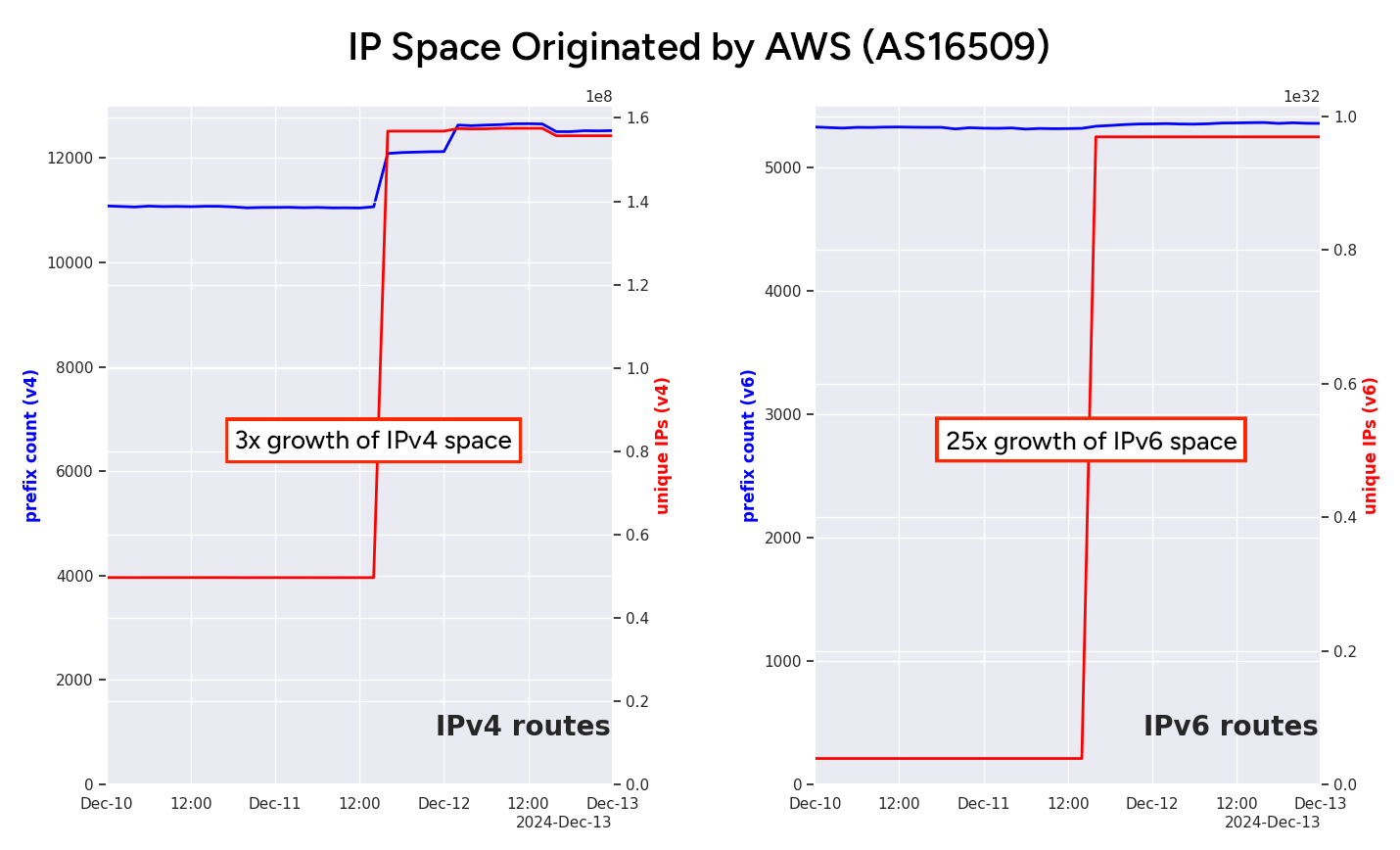

A little more than a year ago, I published a brief post about AWS announcing over 1,000 new BGP prefixes, including numerous super-aggregate prefixes covering nearly all of the cloud provider’s assigned IP space. The result of this action was a threefold increase in unique IPv4 addresses and a 25-fold increase in IPv6 space announced by AS16509.

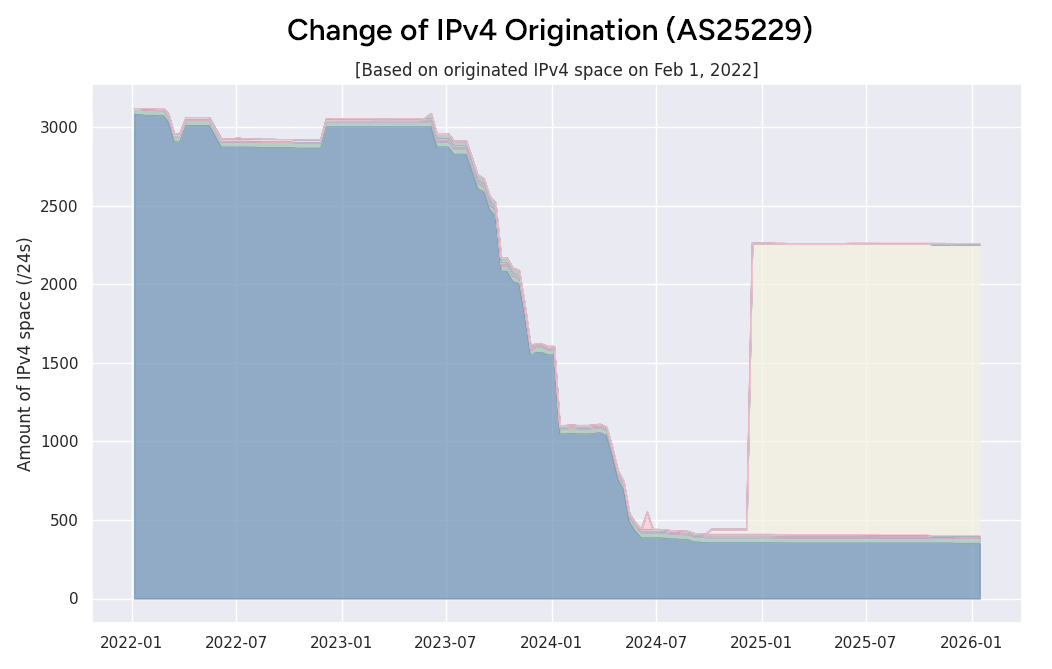

For several years prior to this announcement, AWS had been on a binge, buying up address space from any company willing to sell. One of those companies was Volia (AS25229), which transferred the majority of the IPv4 space it was announcing in 2022 to Amazon in 2024. The big originated by AS16509 helps to bookend the migration of IPv4 from Ukraine to AWS in the graphic below:

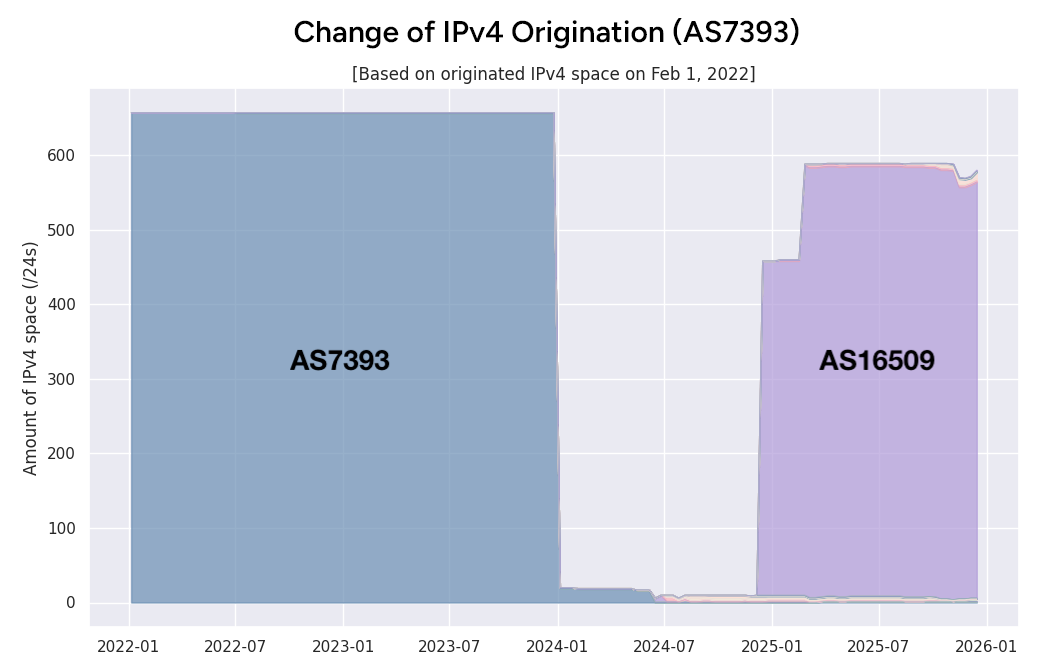

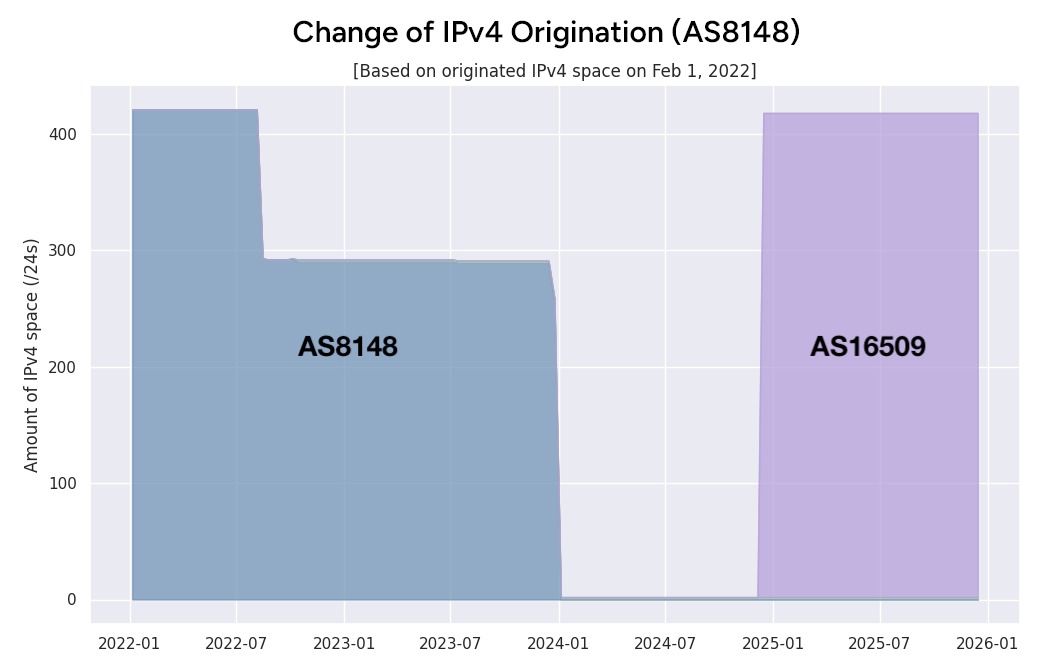

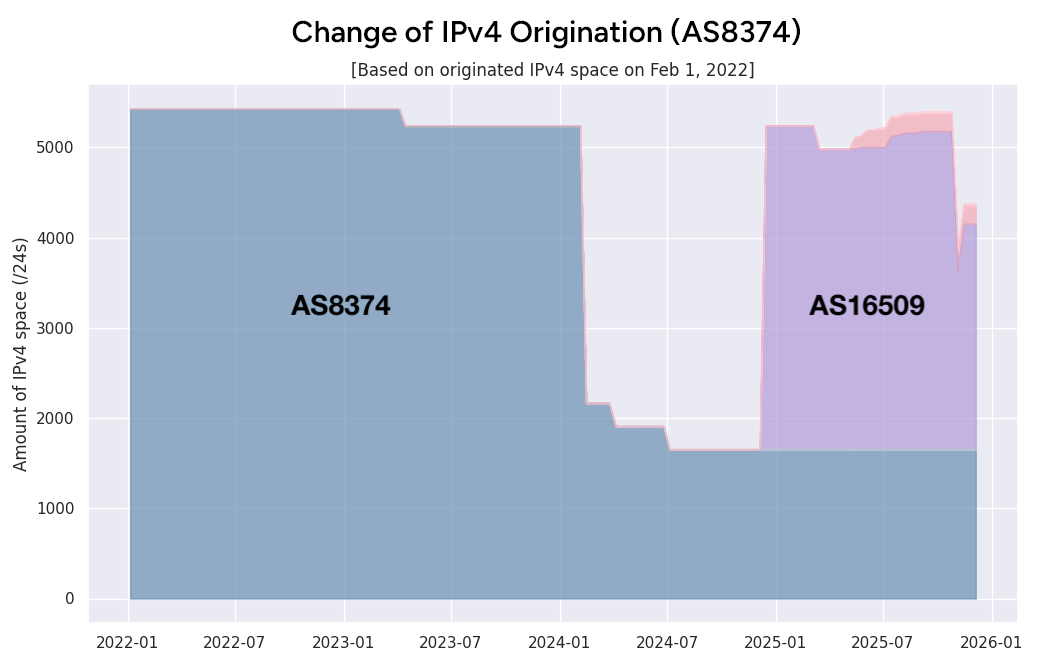

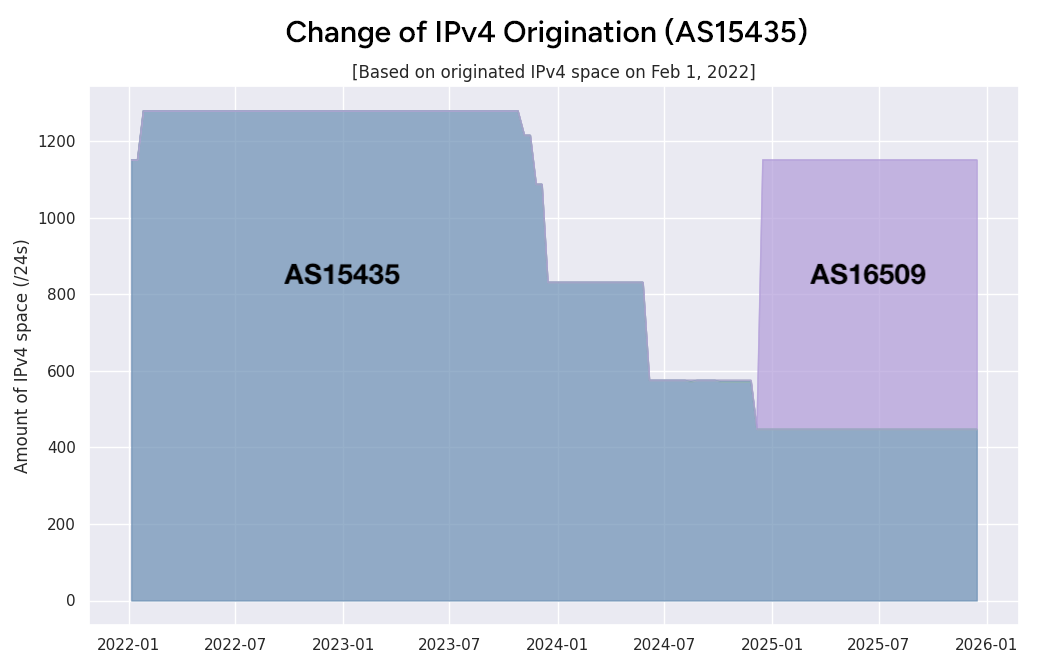

Volia was just one of dozens of sources of IPv4 that AWS was tapping into. The four charts in the carousel below show the migration of IPv4 address space from four ASNs: AS7393, AS8148, AS8374, and AS15435 over the past four years. In each case, the network stopped announcing some or all of the IPv4 space it was originating at the beginning of 2022, much of which became part of AWS’s new announcements a year ago.

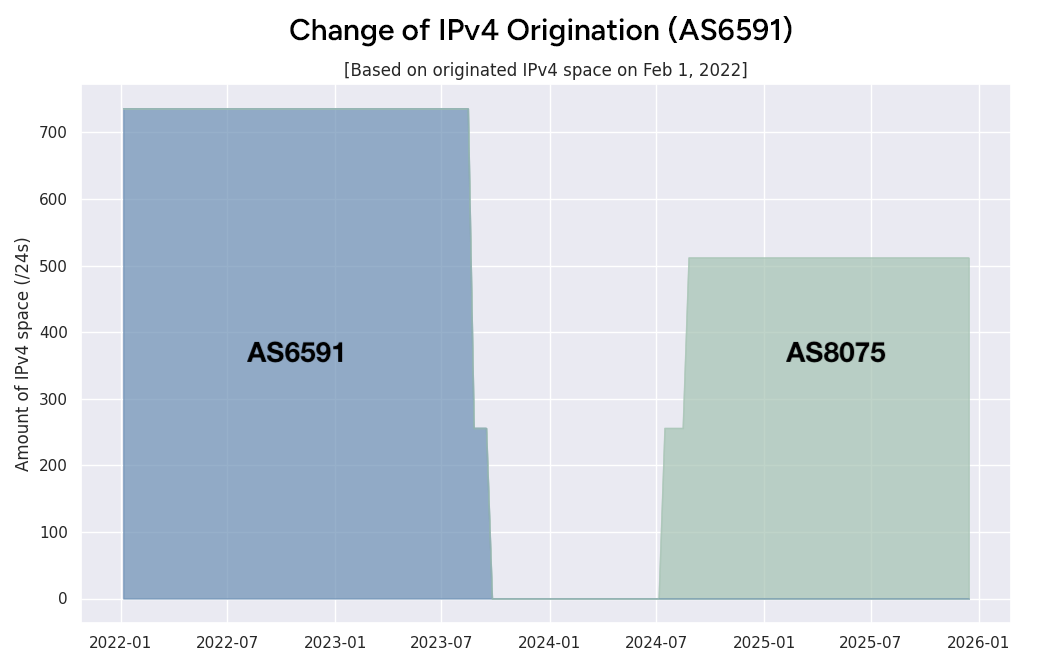

AWS wasn’t the only cloud provider gobbling up IPv4 space. Microsoft (AS8075) began originating its newly acquired trove of IPv4 space in the summer of 2024. Perhaps that was the impetus for AWS’s big jump in originations last year? Similar to the plots above, there are many ASNs that sold off much of their IPv4 space to Microsoft.

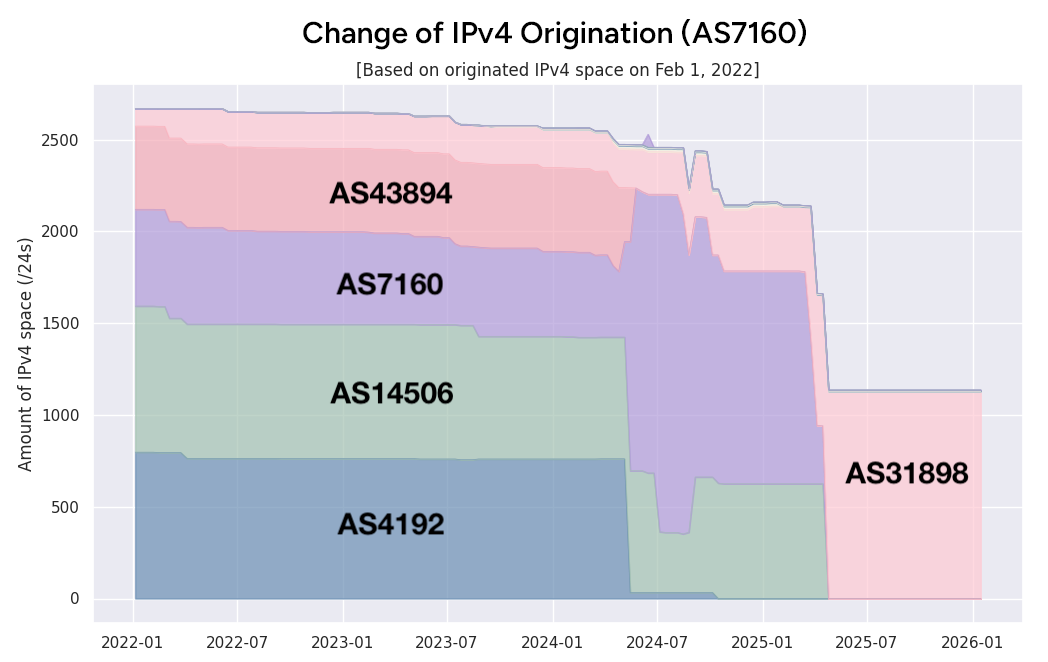

Lastly, Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI, AS31898) has also been gobbling up IPv4 space, but not from other companies like was the case with Amazon and Microsoft. AS31898 has been gathering IPv4 space from other parts of the greater software giant. The IPv4 space originated by Oracle ASNs 43898, 14506, 9105, 4192, 7160, 43894, and 43383 has all been entirely consumed by AS31898.

Conclusion

The advent of private party sales of address space created an IPv4 marketplace that took off in 2015 and introduced a new player in the internet ecosystem: the IPv4 broker. IPv4 leasing came a few years later and added the flexibility of temporary usage that didn’t require an RIR-mediated transfer of ownership. IPv4 leasing has become a source of revenue for some networks, including the beleaguered telecoms in Ukraine, but have enabled residential proxy services to launder illicit traffic.

The BGP cleanup effort at AT&T is significant and should be commended. It isn’t often that we get to share a success story, so let’s take a moment and commend a job well done. Other networks should adopt a similar approach. Now that getting an ASN assignment is trivial and running BGP (including the equipment, software, and knowledge) is within anyone’s reach, there’s no excuse for a customer not to originate its own prefixes with its own ASN. You just need to be ready to handle customers being cranky about it.

The migrations of IPv4 address space, either from Ukraine and Iran, or two the major cloud providers, show that, regardless of whether or not we’ve hit peak IPv4, the legacy address space still holds tremendous value as a commodity in the global marketplace.

Note: The BGP analysis in this article made use of data from the Routeviews project at the University of Oregon.